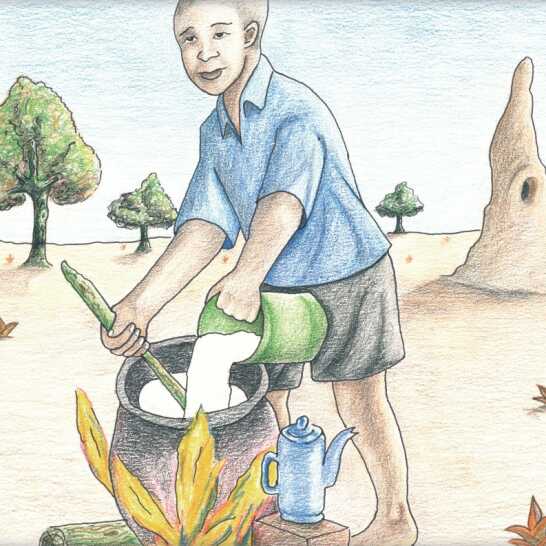

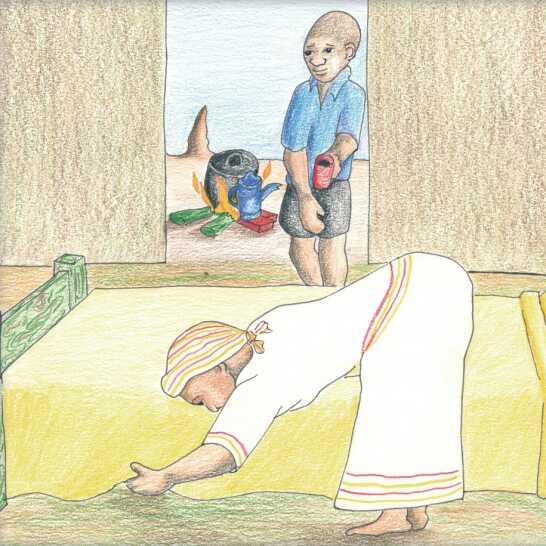

Jeden Morgen wachte Hilifa früh auf, um das Frühstück für seine Mutter vorzubereiten. Sie war in letzter Zeit oft krank, und Hilifa lernte, wie er sich um seine Mutter und sich selbst kümmern konnte. Als seine Mutter zu krank war, um aufzustehen, machte er ein Feuer, um Wasser für Tee zu kochen. Er brachte seiner Mutter den Tee und bereitete den Frühstücksbrei zu. Manchmal war seine Mutter zu schwach, um ihn zu essen. Hilifa machte sich Sorgen um seine Mutter. Sein Vater war vor zwei Jahren gestorben, und nun war auch seine Mutter krank. Sie war sehr dünn, genau wie sein Vater es gewesen war.

Every morning Hilifa woke up early to prepare breakfast for his mother. She had been sick a lot recently and Hilifa was learning how to look after his mother and himself. When his mother was too ill to get up he would make a fire to boil water to make tea. He would take tea to his mother and prepare porridge for breakfast. Sometimes his mother was too weak to eat it. Hilifa worried about his mother. His father had died two years ago, and now his mother was ill too. She was very thin, just like his father had been.

Eines Morgens fragte er seine Mutter: “Was ist los, Mama? Wann wird es dir besser gehen? Du kannst nicht mehr kochen. Du kannst nicht auf dem Feld arbeiten oder das Haus putzen. Du bereitest mir kein Pausenbrot zu und wäschst meine Schuluniform nicht…” “Hilifa, mein Sohn, du bist erst neun Jahre alt und du kümmerst dich gut um mich.” Sie sah den Jungen an und überlegte, was sie ihm sagen sollte. Würde er es verstehen? “Ich bin sehr krank. Du hast im Radio von der Krankheit namens AIDS gehört. Ich habe diese Krankheit”, sagte sie ihm. Hilifa war einige Minuten lang still. “Heißt das, du wirst sterben wie Papa?” “Es gibt kein Heilmittel für AIDS.”

One morning he asked his mother, “What is wrong Mum? When will you be better? You don’t cook anymore. You can’t work in the field or clean the house. You don’t prepare my lunchbox, or wash my uniform…” “Hilifa my son, you are only nine years old and you take good care of me.” She looked at the young boy, wondering what she should tell him. Would he understand? “I am very ill. You have heard on the radio about the disease called AIDS. I have that disease,” she told him. Hilifa was quiet for a few minutes. “Does that mean you will die like Daddy?” “There is no cure for AIDS.”

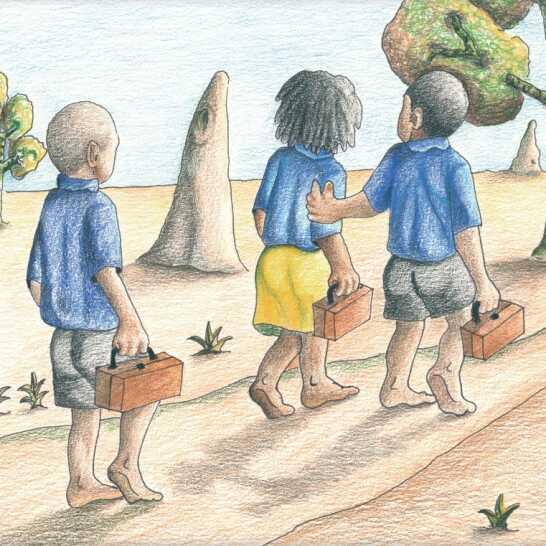

Hilifa ging nachdenklich zur Schule. Er konnte sich nicht an den Gesprächen und den Spielen seiner Freunde beteiligen, als sie vorbeigingen. “Was ist los?”, fragten sie ihn. Aber Hilifa konnte nicht antworten, denn die Worte seiner Mutter klangen in seinen Ohren: “Keine Heilung. Keine Heilung.” Wie sollte er für sich selbst sorgen, wenn seine Mutter starb, fragte er sich. Wo würde er leben? Woher sollte er Geld für Essen bekommen?

Hilifa walked to school thoughtfully. He couldn’t join in the chatter and games of his friends as they walked along. “What’s wrong?” they asked him. But Hilifa couldn’t answer, his mother’s words were ringing in his ears, “No cure. No cure.” How could he look after himself if his mother died, he worried. Where would he live? Where would he get money for food?

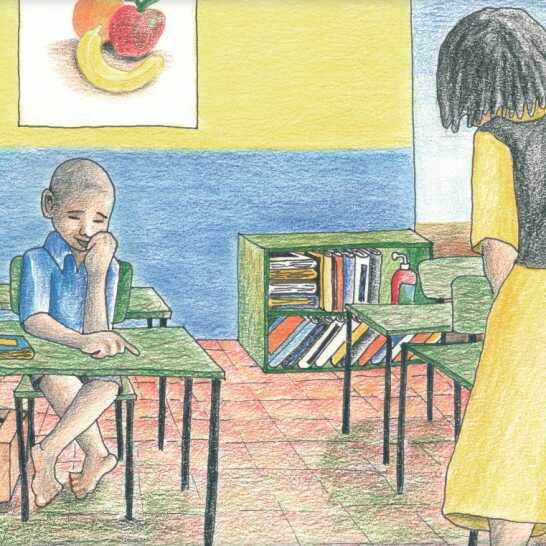

Hilifa saß an seinem Tisch. Er fuhr mit dem Finger über die abgenutzten Holzmarkierungen: “Keine Heilung. Keine Heilung.” “Hilifa? Hilifa, bist du bei uns?” Hilifa schaute auf. Frau Nelao stand über ihm. “Steh auf Hilifa! Was war meine Frage?” Hilifa sah auf seine Füße hinunter. “Da unten wirst du die Antwort nicht finden!”, erwiderte sie. “Magano, sag Hilifa die Antwort.” Hilifa schämte sich so sehr, Frau Nelao hatte ihn noch nie angeschrien.

Hilifa sat at his desk. He traced the worn wood markings with his finger, “No cure. No cure.” “Hilifa? Hilifa, are you with us?” Hilifa looked up. Ms. Nelao was standing over him. “Stand up Hilifa! What was my question?” Hilifa looked down at his feet. “You won’t find the answer down there!” she retorted. “Magano, tell Hilifa the answer.” Hilifa felt so ashamed, Ms. Nelao had never shouted at him before.

Hilifa mühte sich durch den Vormittag. In der Pause saß er im Klassenzimmer. “Ich habe Bauchschmerzen”, log er seine Freunde an. Es war keine große Lüge, er fühlte sich tatsächlich krank und seine besorgten Gedanken schwirrten in seinem Kopf wie wütende Bienen. Frau Nelao beobachtete ihn schweigend. Sie fragte ihn, was los sei. “Nichts”, antwortete er. Ihre Ohren hörten die Müdigkeit und Sorge in seiner Stimme. Ihre Augen sahen die Angst, die er so sehr zu verstecken suchte.

Hilifa struggled through the morning. At break time he sat in the classroom. “I have a stomach ache,” he lied to his friends. It wasn’t a big lie, he did feel sick, and his worried thoughts buzzed inside his head like angry bees. Ms. Nelao watched him quietly. She asked him what was wrong. “Nothing,” he replied. Her ears heard the tiredness and worry in his voice. Her eyes saw the fear he was trying so hard to hide.

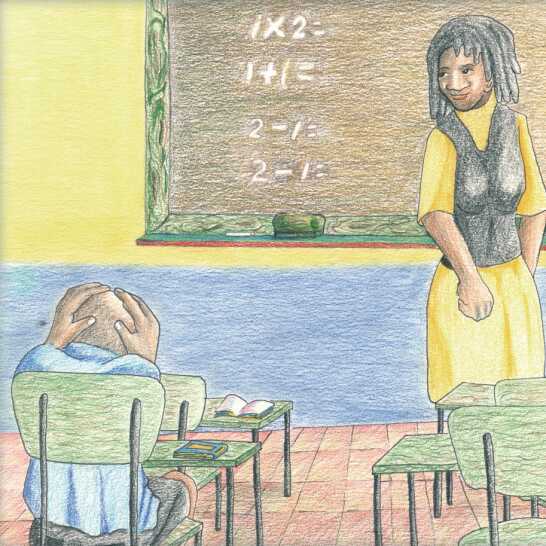

Als Hilifa versuchte, zu rechnen, sprangen die Zahlen in seinem Kopf herum. Er konnte sie nicht lange genug behalten, um sie zu zählen. Bald gab er auf. Stattdessen dachte er an seine Mutter. Seine Finger begannen, seine Gedanken zu zeichnen. Er zeichnete seine Mutter in ihrem Bett. Er zeichnete sich selbst neben dem Grab seiner Mutter stehend. “Bitte sammelt alle Bücher ein”, rief Frau Nelao. Hilifa sah plötzlich die Zeichnungen in seinem Buch und versuchte, die Seite herauszureißen, aber es war zu spät. Ein Mitschüler brachte sein Buch zu Frau Nelao.

When Hilifa tried to do his maths the numbers jumped around in his head. He couldn’t keep them still long enough to count them. He soon gave up. He thought of his mother instead. His fingers began to draw his thoughts. He drew his mother in her bed. He drew himself standing beside his mother’s grave. “Maths monitors, collect all the books please,” called Ms. Nelao. Hilifa suddenly saw the drawings in his book and tried to tear out the page, but it was too late. The monitor took his book to Ms. Nelao.

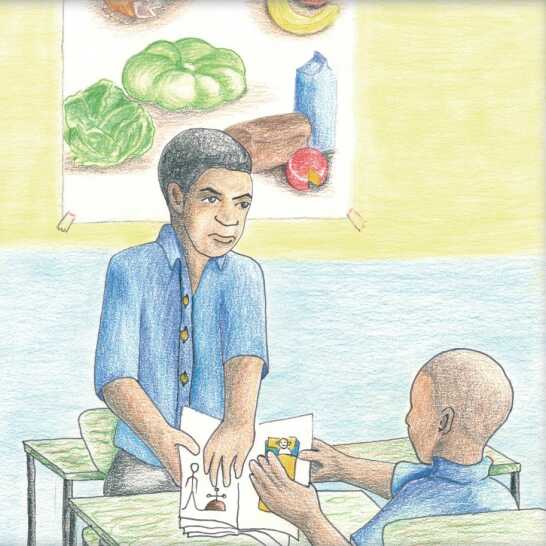

Frau Nelao betrachtete Hilifas Zeichnungen. Als die Kinder sich auf den Heimweg machten, rief sie: “Komm her, Hilifa. Ich möchte mit dir reden.” “Was ist passiert?”, fragte sie sanft. “Meine Mutter ist krank. Sie hat mir gesagt, dass sie AIDS hat. Wird sie sterben?” “Ich weiß es nicht, Hilifa, aber wenn sie AIDS hat, ist sie sehr krank. Es gibt keine Heilung.” Wieder diese Worte: “Keine Heilung. Keine Heilung.” Hilifa begann zu weinen. “Geh nach Hause, Hilifa”, sagte sie. “Ich werde kommen und deine Mutter besuchen.”

Ms. Nelao looked at Hilifa’s drawings. When the children were leaving to go home she called, “Come here Hilifa. I want to talk to you.” “What’s wrong?” she asked him gently. “My mother is ill. She told me she has AIDS. Will she die?” “I don’t know, Hilifa, but she is very ill if she has AIDS. There is no cure.” Those words again, “No cure. No cure.” Hilifa began to cry. “Go home, Hilifa,” she said. “I will come and visit your mother.”

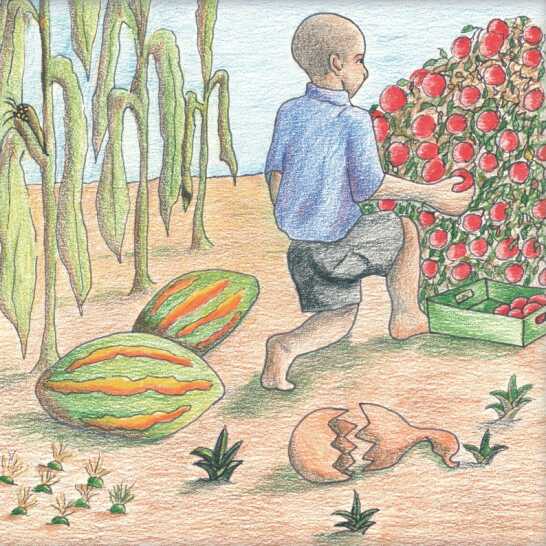

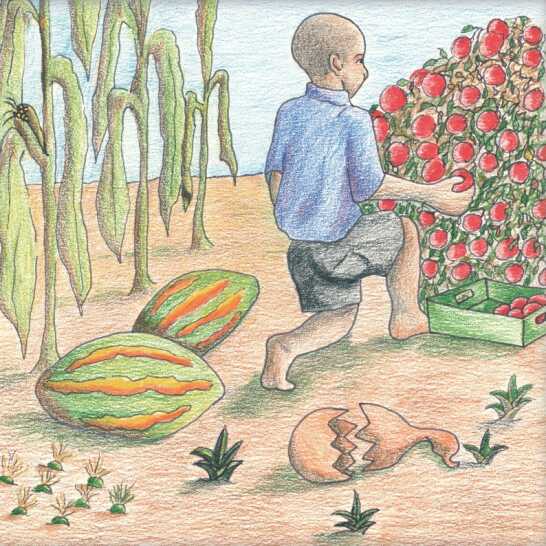

Hilifa ging nach Hause und fand seine Mutter bei der Zubereitung des Mittagessens. “Ich habe heute für dich gekocht, Hilifa, aber jetzt bin ich sehr müde. Kümmere dich um den Gemüsegarten und bring ein paar Tomaten in den Laden. Sie werden sie für uns verkaufen.” Nach dem Mittagessen ging Hilifa zum Gemüsebeet. Er betrachtete die leuchtenden Farben des Gemüses, leuchtend rote Tomaten und Chilis, lange grüne Bohnen und dunkelgrünen Spinat, die grünen Blätter der Süßkartoffel und den hohen goldenen Mais. Er goss den Garten und pflückte eine Tüte voller reifer roter Tomaten, um sie in den Laden zu bringen. “Was wird wohl aus unserem Garten werden, wenn seine Mutter stirbt?”, fragte er sich.

Hilifa went home and found his mother preparing lunch. “I’ve cooked for you today, Hilifa, but now I am very tired. Look after the vegetable garden and take some tomatoes to the shop. They will sell them for us.” After lunch Hilifa went to the vegetable plot. He looked at the bright colours of the vegetables, bright red tomatoes and chillies, long green beans and dark green spinach, the green leaves of the sweet potato and tall golden maize. He watered the garden and picked a bag full of ripe red tomatoes to take to the shop. “What would happen to their garden if his mother died?” he wondered.

Frau Nelao kam kurz nachdem Hilifa gegangen war. Sie unterhielt sich lange mit seiner Mutter. Sie fragte Hilifas Mutter: “Meme Ndapanda, nimmst du die Medizin gegen AIDS?” “Nach dem Tod meines Mannes schämte ich mich zu sehr, um zum Arzt zu gehen”, erzählte sie Frau Nelao. “Ich habe gehofft, ich habe mich nicht angesteckt. Als ich krank wurde und zur Ärztin ging, sagte sie mir, es sei zu spät. Die Medizin würde mir nicht helfen. Frau Nelao erklärte Meme Ndapanda, was sie tun konnte, um Hilifa zu helfen.

Ms. Nelao arrived soon after Hilifa left. She spent a long time talking to his mother. She asked Hilifa’s mother, “Meme Ndapanda, are you taking the medicine for AIDS?” “After my husband died I was too ashamed to go to the doctor,” she told Ms. Nelao. “I kept hoping I wasn’t infected. When I became ill and went to the doctor she told me it was too late. The medicine would not help me.” Ms. Nelao told Meme Ndapanda what to do to help Hilifa.

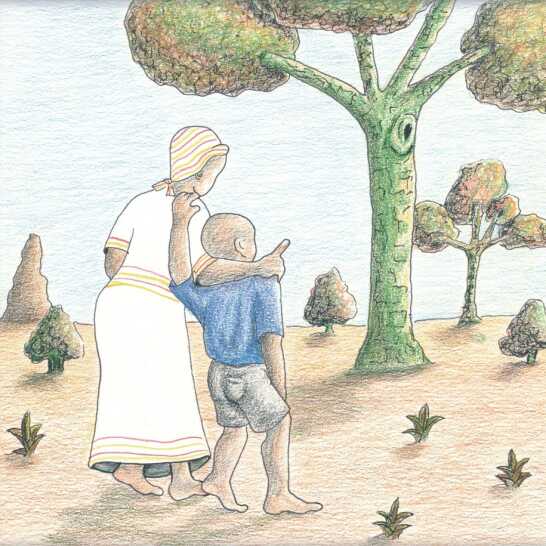

Als Hilifa nach Hause kam, fragte ihn seine Mutter: “Hilifa, mein Sohn, ich möchte mit dir spazieren gehen. Kannst du mir helfen?” Hilifa nahm den Arm seiner Mutter, und sie lehnte sich an ihn. Sie gingen dorthin, wo die hohen Dornenbäume wuchsen. Sie fragte ihn: “Weißt du noch, wie du hier mit deinem Cousin Kunuu Fußball gespielt hast? Du hast den Ball gegen den Baum geschossen und er blieb in den Dornen hängen. Dein Vater holte sich Kratzer, als er ihn für dich herausgezogen hat..”

When Hilifa came home his mother asked him, “Hilifa, my son, I want to take a walk with you. Will you help me?” Hilifa took his mother’s arm and she leaned on him. They walked to where the tall thorn trees grew. She asked him, “Do you remember playing football here with your cousin Kunuu? You kicked the ball into the tree and it got stuck on the thorns. Your father got scratched getting it down for you.”

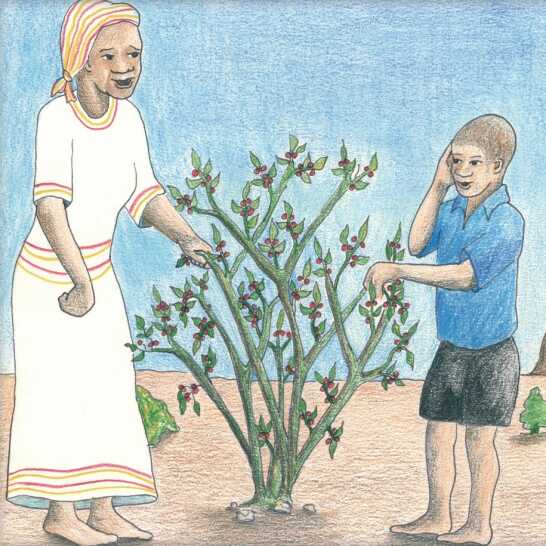

“Sieh mal, da ist ein Omandjembere Strauch. Geh und pflücke ein paar, um sie mit nach Hause zu nehmen.” Als Hilifa die süßen Beeren pflückte, sagte sie: “Weißt du noch, als du klein warst, hast du die Beeren und den Samen darin gegessen. Du bist eine Woche lang nicht zur Toilette gegangen!” “Ja, mein Bauch war sooo hart”, erinnerte sich Hilifa und lachte.

“Look, there’s an omandjembere bush. Go and pick some to take home.” When Hilifa was picking the sweet berries, she said, “Do you remember when you were small you ate the berries and the seed inside. You didn’t go to the toilet for a week!” “Yes, my stomach was sooo sore,” remembered Hilifa, laughing.

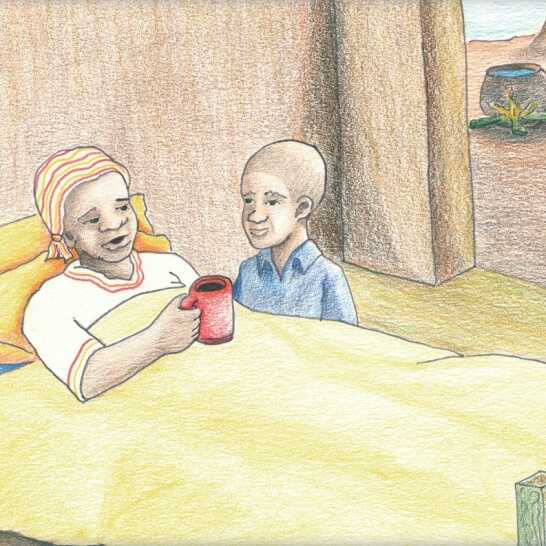

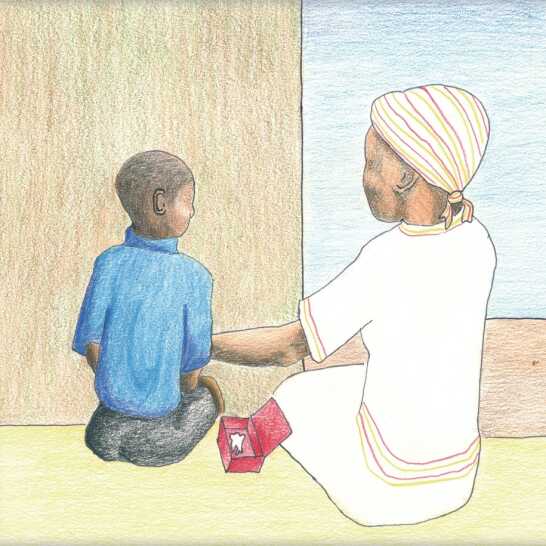

Als sie nach Hause kamen, war Hilifas Mutter sehr müde. Hilifa machte Tee. Meme Ndapanda holte eine kleine Schachtel unter ihrem Bett hervor. “Hilifa, das ist für dich. In dieser Schachtel sind Dinge, die dir helfen werden, dich daran zu erinnern, woher du kommst.”

When they got home Hilifa’s mother was very tired. Hilifa made some tea. Meme Ndapanda took a small box from under her bed. “Hilifa, this is for you. In this box are things that will help you remember where you come from.”

Sie holte ein Erinnerungsstück nach dem anderen aus der Schachtel. “Das ist ein Foto von deinem Vater, wie er dich im Arm hält. Du warst sein erstgeborener Sohn. Auf diesem Foto habe ich dich zu deinen Großeltern gebracht, sie waren so glücklich. Das ist der erste Zahn, den du verloren hast. Erinnerst du dich daran, wie du geweint hast und ich dir versprechen musste, dass andere nachwachsen würden? Das ist die Brosche, die dein Vater mir geschenkt hat, als wir ein Jahr verheiratet waren.”

She took the mementos out of the box one by one. “This is a photo of your father holding you. You were his firstborn son. This photo is when I took you to see your grandparents, they were so happy. This is the first tooth you lost. Do you remember how you cried and I had to promise you that more would grow. This is the brooch your father gave me when we were married for one year.”

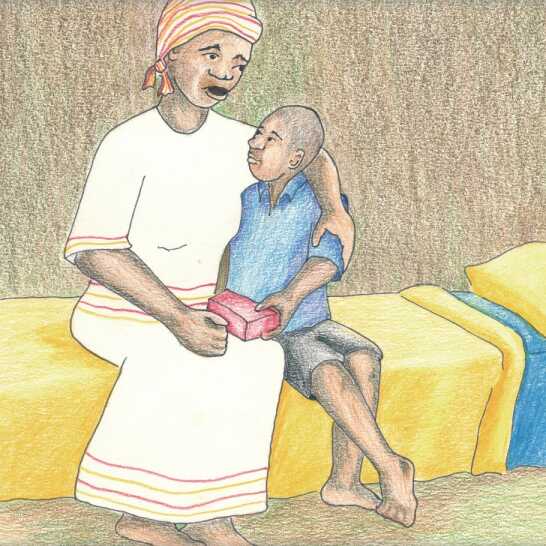

Hilifa hielt die Schachtel und begann zu weinen. Seine Mutter drückte ihn an sich und sprach ein Gebet: “Möge der Herr dich beschützen und behüten.” Sie hielt ihn fest, während sie sprach. “Hilifa, mein Sohn. Du weißt, dass ich sehr krank bin und bald werde ich bei deinem Vater sein. Ich möchte nicht, dass du traurig bist. Denk daran, wie sehr ich dich liebe. Erinnere dich daran, wie sehr dein Vater dich geliebt hat.”

Hilifa held the box and began to cry. His mother held him close by her side and said a prayer, “May the Lord protect you and keep you safe.” She held him as she spoke. “Hilifa, my son. You know that I am very ill, and soon I will be with your father. I don’t want you to be sad. Remember how much I love you. Remember how much your father loved you.”

Seine Mutter fuhr fort: “Onkel Kave aus Oshakati schickt uns Geld, wenn er kann. Er hat mir gesagt, dass er für dich sorgen wird. Ich habe mit ihm darüber gesprochen. Du wirst mit Kunuu, seinem Sohn, zur Schule gehen. Kunuu ist in der 4. Klasse wie du. Sie werden sich gut um dich kümmern.” “Ich mag Onkel Kave und Tante Muzaa”, sagte Hilifa. “Und ich spiele gern mit Kunuu. Würdest du gesund werden, wenn sie sich um dich kümmern?” “Nein, mein Sohn. Ich werde nicht gesund werden. Du kümmerst dich sehr gut um mich. Ich bin stolz darauf, einen so guten Sohn zu haben.”

His mother continued, “Uncle Kave from Oshakati sends us money when he can. He told me that he will care for you. I have talked to him about it. You’ll go to school with Kunuu, his son. Kunuu is in Grade 4 like you. They will take good care of you.” “I like Uncle Kave and Aunt Muzaa,” said Hilifa. “And I like playing with Kunuu. Would you become well if they look after you?” “No, my son. I won’t become well. You look after me very well. I am proud to have such a good son.”

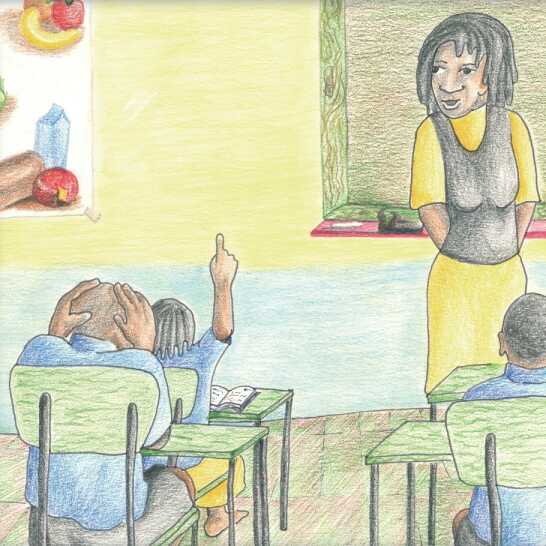

Am nächsten Morgen unterrichtete Frau Nelao sie in der Schule über HIV und AIDS. Die Schüler sahen ängstlich aus. Sie hatten im Radio von dieser Krankheit gehört, aber zu Hause sprach niemand darüber. “Woher kommt sie?”, fragte Magano. “Wie steckt man sich an?”, fragte Hidipo. Frau Nelao erklärte, dass HIV der Name des Virus ist. “Wenn eine Person das HIV-Virus im Blut hat, sieht sie noch gesund aus. Wir sagen, sie haben AIDS, wenn sie krank werden.”

The next morning at school Ms. Nelao taught them about HIV and AIDS. The learners looked afraid. They heard about this illness on the radio, but no-one spoke about it at home. “Where does it come from?” asked Magano. “How do we catch it?” asked Hidipo. Ms. Nelao explained that HIV is the name of a virus. When a person has the HIV virus in their blood they still look healthy. “We say they have AIDS when they become ill.”

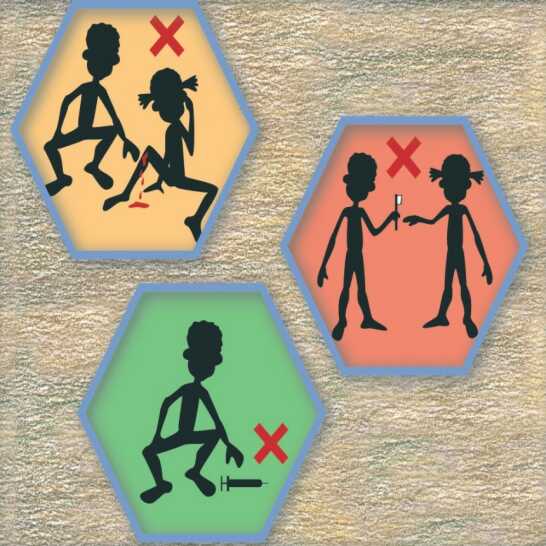

Frau Nelao erklärte einige der Möglichkeiten, wie wir uns mit HIV anstecken können. “Wenn jemand HIV oder AIDS hat, können wir uns über sein Blut mit dem Virus infizieren. Wir sollten niemals Rasierklingen oder Zahnbürsten gemeinsam benutzen. Wenn wir uns Ohrringe stechen lassen, müssen wir sterilisierte Klingen und Nadeln verwenden. Sie erklärte, wie Nadeln und Klingen sterilisiert werden sollten. “Wenn wir uns verletzen und Blut fließt, müssen wir einen Erwachsenen bitten, die Wunde zu reinigen. Wir müssen die Wunde abdecken, um sie zu schützen”, erklärte sie ihnen.

Ms. Nelao explained some of the ways we can be infected with HIV. “If someone has HIV or AIDS we can catch the virus from their blood. We should never share razors or toothbrushes. If we get our ears pierced we must use sterilised blades and needles.” She explained how needles and blades should be sterilised. “If we hurt ourselves and there is blood we must ask an adult to clean the wound. We must cover the wound to protect it,” she told them.

Dann zeigte sie ihnen eine Übersicht. “Das sind alle Möglichkeiten, wie man sich nicht mit HIV anstecken kann”, erklärte sie ihnen. “Man kann sich nicht mit HIV anstecken, wenn man die Toilette benutzt oder ein Bad mit anderen teilt. Auch das Umarmen, Küssen oder Händeschütteln mit jemandem, der HIV oder AIDS hat, ist ungefährlich. Es ist in Ordnung, Tassen und Teller mit jemandem zu teilen, der HIV hat oder an Aids erkrankt ist. Und man kann sich nicht bei jemandem anstecken, der hustet oder niest. Außerdem kann man sich nicht durch Mücken oder andere stechende Insekten wie Läuse oder Wanzen anstecken.

Then she showed them a chart. “These are all the ways you can’t catch HIV,” she told them. “You won’t get HIV from using the toilet, or sharing a bath. Hugging, kissing or shaking hands with someone with HIV or AIDS is also safe. It’s OK to share cups and plates with someone who has HIV or AIDS. And you can’t catch it from someone who is coughing or sneezing. Also, you can’t get it from mosquitoes or other biting insects like lice or bedbugs.”

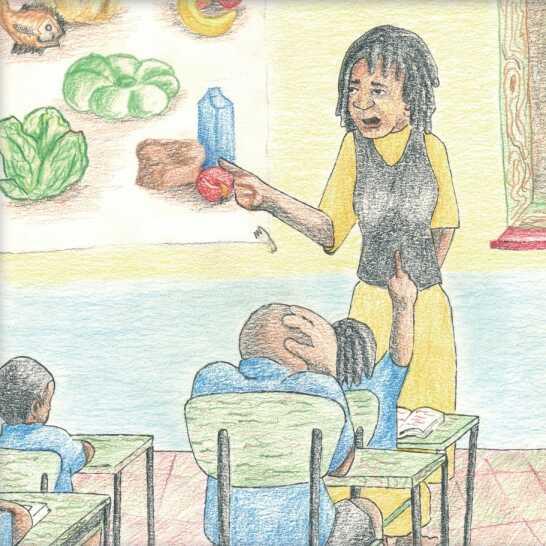

“Was macht man, wenn man es hat?”, fragte Magano. “Nun, man muss auf sich aufpassen und sich gesund ernähren. Sieh dir unsere Lebensmitteltabelle an”, sagte sie. “Wer kann sich erinnern, welche Lebensmittel gut für uns sind?”, fragte sie.

“What do you do if you’ve got it?” asked Magano. “Well, you must take care of yourself and eat lots of healthy food. Look at our food chart,” she said. “Who can remember what food is good for you?” she asked.

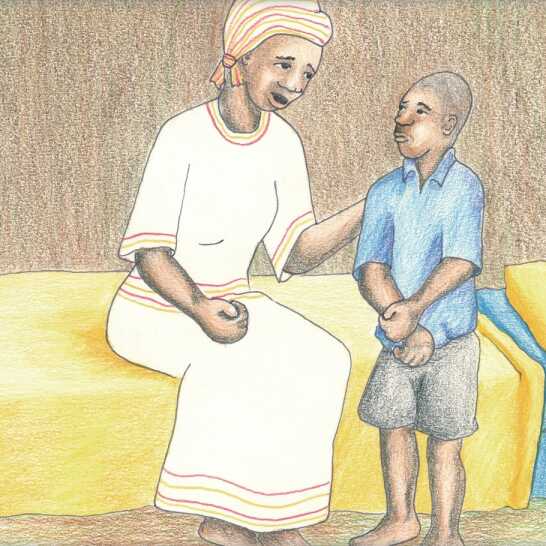

Als Hilifa nach Hause kam, erzählte er seiner Mutter, was er an diesem Tag in der Schule gelernt hatte. “Frau Nelao hat uns etwas über HIV und AIDS erzählt und wie man sich um kranke Menschen kümmert. Magano und Hidipo werden mir bei der Hausarbeit helfen und wir werden unsere Hausaufgaben zusammen machen”, sagte er ihr.

When Hilifa got home he told his mother what he had learned at school that day. “Ms. Nelao told us about HIV and AIDS and how to look after someone who’s ill. Magano and Hidipo are going to help me with my chores and we will do our homework together,” he told her.

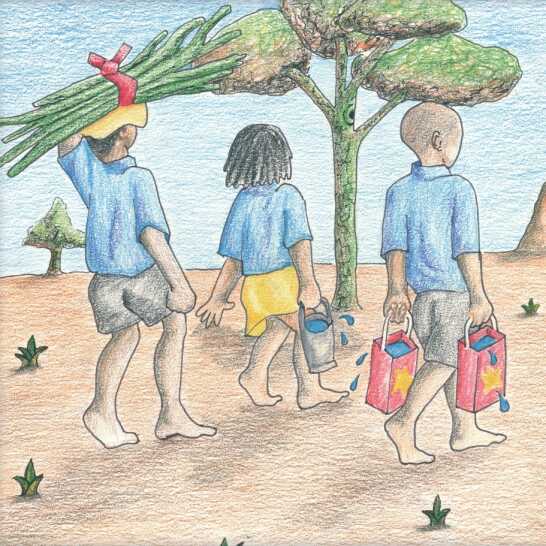

An diesem Nachmittag kam Magano und half Hilifa, Wasser zu holen. Hidipo half ihm, Feuerholz zu sammeln. Dann saßen sie im Schatten des Marulabaums und machten ihre Hausaufgaben.

That afternoon Magano came and helped Hilifa to fetch water. Hidipo helped him to gather firewood. Then they sat and did their homework in the shade of the marula tree.

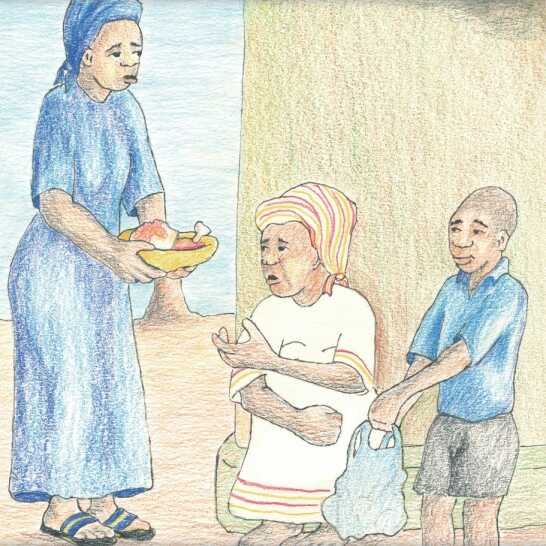

Frau Nelao hatte auch ilifas Nachbarn erzählt, dass er sich um seine Mutter kümmert. Sie hatten versprochen, ihm zu helfen. Jeden Abend kam ein anderer Nachbar mit warmem Essen für sie. Hilifa gab ihnen immer etwas Gemüse aus ihrem Garten.

Ms. Nelao had also told Hilifa’s neighbours that he was looking after his mother. They had promised to help him. Every night a different neighbour came with hot food for them to eat. Hilifa always gave them some vegetables from the garden.

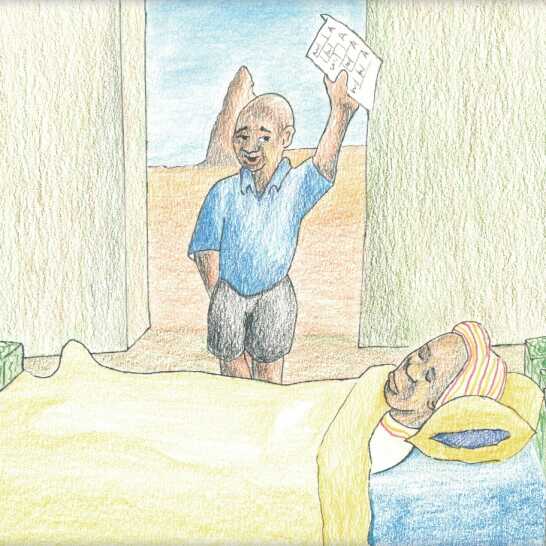

Am letzten Tag des Schuljahres war Hilifa sehr glücklich. Er rannte nach Hause, um seiner Mutter sein Zeugnis zu zeigen. Er lief in den Hof und rief: “Mama. Mama. Schau dir mein Zeugnis an. Ich habe eine Eins, eine Eins und noch mehr Einsen bekommen.” Hilifa fand seine Mutter im Bett. “Mama!”, rief er. “Mama, wach auf!” Sie wachte nicht auf.

On the last day of the school term Hilifa was very happy. He ran home to show his mother his report card. He ran into the yard calling, “Mum. Mum. Look at my report card. I have got ‘A’, ‘A’, and more ‘A’s’.” Hilifa found his mother lying in bed. “Mum!” he called. “Mum! Wake up!” She didn’t wake up.

Hilifa lief zu den Nachbarn. “Meine Mutter. Meine Mutter. Sie wacht nicht mehr auf”, weinte er. Die Nachbarn gingen mit Hilifa nach Hause und fanden Meme Ndapanda in ihrem Bett. “Sie ist tot, Hilifa”, sagten sie traurig.

Hilifa ran to the neighbours. “My Mum. My Mum. She won’t wake up,” he cried. The neighbours went home with Hilifa and found Meme Ndapanda in her bed. “She is dead, Hilifa,” they said sadly.

Sehr schnell verbreitete sich die Nachricht, dass Meme Ndapanda tot war. Das Haus war voller Familie, Nachbarn und Freunden. Sie beteten für Hilifas Mutter und sangen Lieder. Sie sprachen über all die guten Dinge, die sie über sie wussten.

Very quickly the news spread that Meme Ndapanda was dead. The house was full of family, neighbours and friends. They prayed for Hilifa’s mother and sang hymns. They talked about all the good things they knew about her.

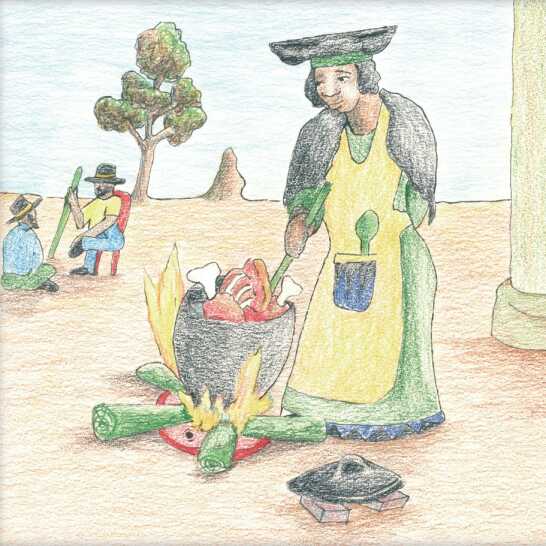

Tante Muzaa kochte für alle Besucher. Onkel Kave sagte Hilifa, dass sie ihn nach der Beerdigung zurück nach Oshakati bringen würden. Sein Großvater erzählte ihm Geschichten über seine Mutter, als sie noch ein kleines Mädchen war.

Aunt Muzaa cooked for all the visitors. Uncle Kave told Hilifa that they would take him back to Oshakati after the funeral. His Grandfather told him stories about his mother when she was a little girl.

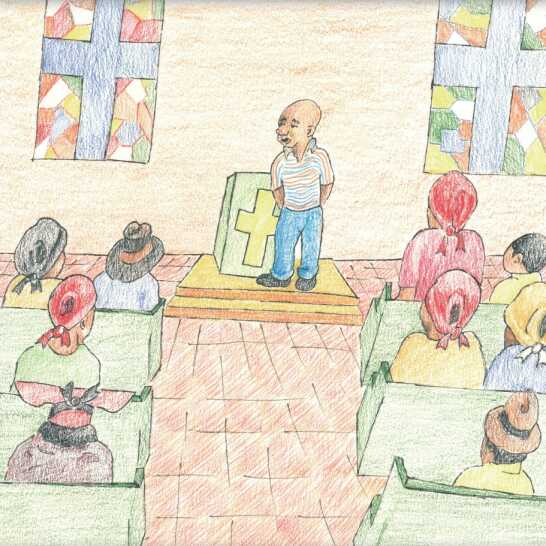

Bei der Beerdigung ging Hilifa in der Kirche nach vorne und erzählte allen von seiner Mutter. “Meine Mutter hat mich geliebt und sich sehr gut um mich gekümmert. Sie sagte mir, ich soll fleißig lernen, damit ich einen guten Beruf bekomme. Sie wollte, dass ich glücklich bin. Ich werde hart lernen und hart arbeiten, damit sie stolz auf mich sein kann.”

At the funeral Hilifa went to the front of the church and told everyone about his mother. “My mother loved me and looked after me very well. She told me to study hard so that I could get a good job. She wanted me to be happy. I will study hard and work hard so that she can be proud of me.”

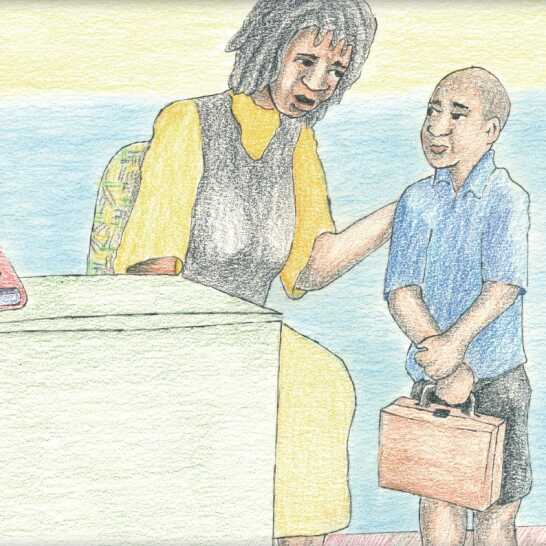

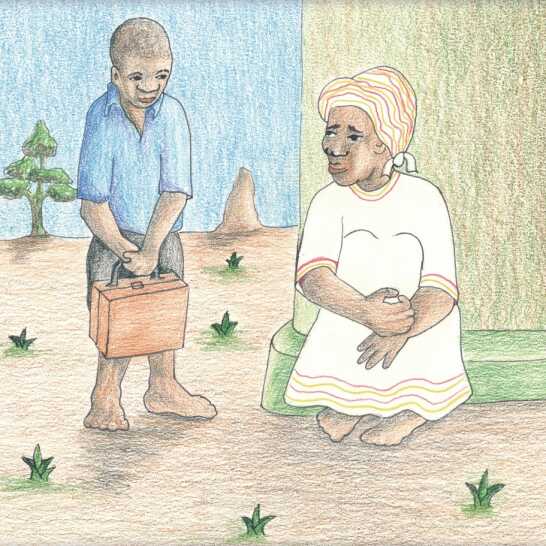

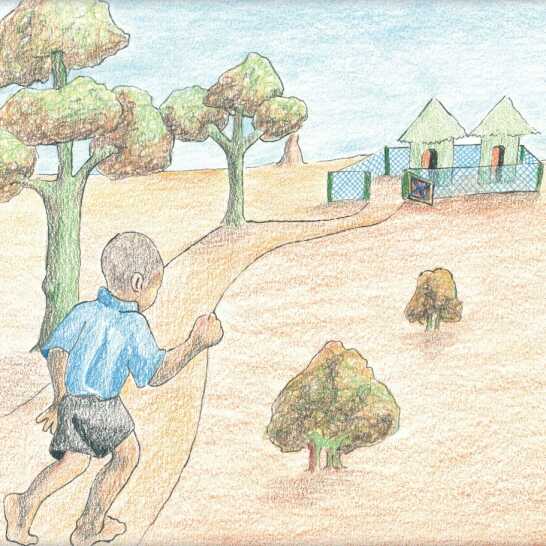

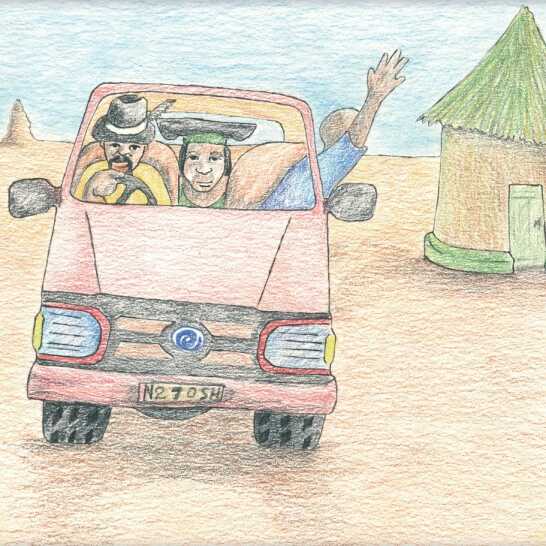

Nach der Beerdigung halfen Onkel Kave und Tante Muzaa Hilifa, seine Sachen zu packen und nach Oshakati zu bringen. “Kunuu freut sich darauf, einen neuen Freund zu haben”, sagten sie ihm. “Wir werden uns um dich kümmern wie um unseren eigenen Sohn.” Hilifa verabschiedete sich von dem Haus und stieg mit ihnen in das Taxi.

After the funeral Uncle Kave and Aunt Muzaa helped Hilifa to pack his things to take to Oshakati. “Kunuu is looking forward to having a new friend,” they told him. “We will care for you like our own son.” Hilifa said goodbye to the house and got into the taxi with them.

Written by: Kandume Ruusa, Sennobia-Charon Katjiuongua, Eliaser Nghitewa

Illustrated by: Jamanovandu Urike

Translated by: Beate Etzel

Read by: Erna Plant

Language: German

Level: Level 5

Source: Orphans need love too from African Storybook

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.