Kehe ngurangura Hilifa karambukanga a wapayikire vawina mukushuko. Kwavera unene ngoli Hilifa akushongerako ashi weni mwakuvhura kupakera mbiri vawina ntani nanaumwendi. Opo vakalire vawina ashi uvera una deke kapi vana kuvhura kurambuka uye kavankedanga mundiro mposhi a yenyekere vawina koshiva. Katwaranga koshiva kwavawina kumwe nakuva pikira vitima vyamukushuko. Maruvede ghamwe vawina kapi kava karanga nankondo dakulya. Hilifa a kalire nashinka shakwa vawina. Vashe kwadohorokire muruku rwamaka mbiri dina kapito po, ano ntantani vawina navo kuna kuvera ngundu. Va tongamine unene, yira moomo nka tupu vyashokire kuvashe.

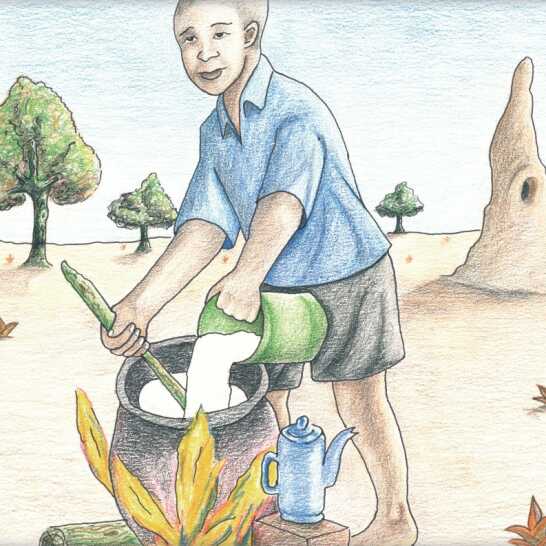

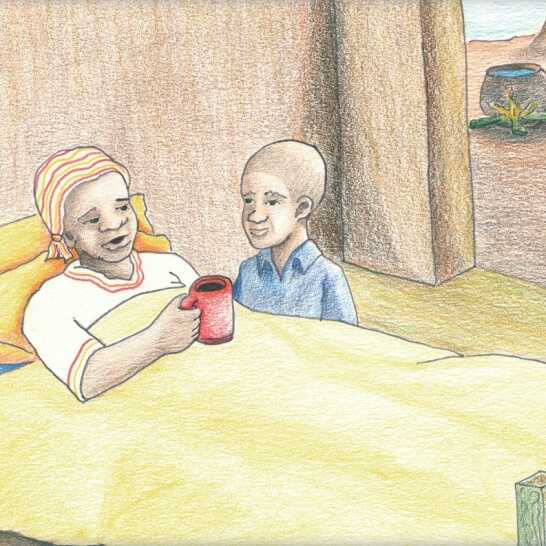

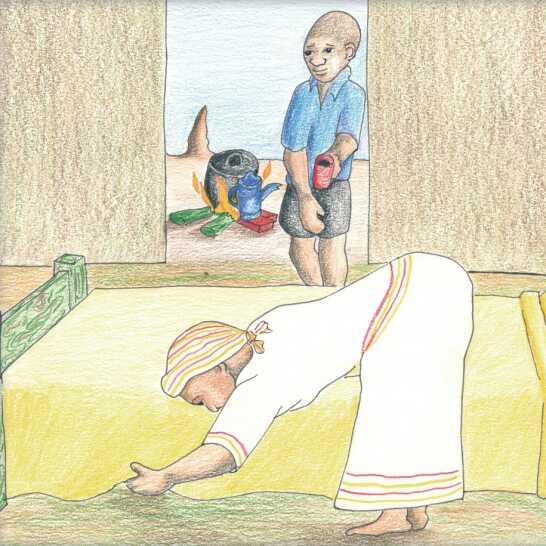

Every morning Hilifa woke up early to prepare breakfast for his mother. She had been sick a lot recently and Hilifa was learning how to look after his mother and himself. When his mother was too ill to get up he would make a fire to boil water to make tea. He would take tea to his mother and prepare porridge for breakfast. Sometimes his mother was too weak to eat it. Hilifa worried about his mother. His father had died two years ago, and now his mother was ill too. She was very thin, just like his father had been.

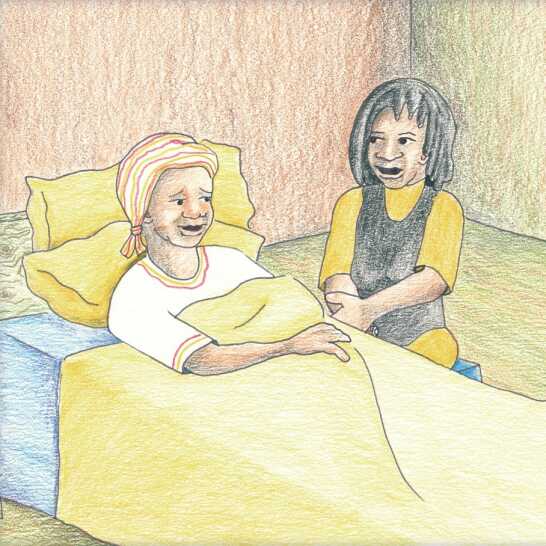

Ngurangura yimwe a pura vawina, “Vinke vina limbo po yina? Tuvede ke ngamu kara hashako? Kapi nka muna kuterayika. Kapi nka muna kuyenga kumafuva nakukenita mundjugho. Kapi nka ndongereranga shibaki shande, ndi kukusha mudwato wande washure…” “Hilifa monande, mwaka doye ne ntane tupu ngoli kuna kuvhura kumpakera mbiri kare.” Ava mu Kenge mumatighona uno, nakukupura ashi va mu tantra. Kuvhura a vi kwate lighano ndi? “Ame kuna kuvera unene. Wa yuva rumwe kuradio uvera wa AIDS. Ogho uvera ngo na kara nagho,” Ava mutantere. Hilifa a mwena tanko kadidi. “Vino kuna kutanta ashi nanwe nga mu fa yira vavava ndi?” “Kundereko vyakuvhura kupangita AIDS.”

One morning he asked his mother, “What is wrong Mum? When will you be better? You don’t cook anymore. You can’t work in the field or clean the house. You don’t prepare my lunchbox, or wash my uniform…” “Hilifa my son, you are only nine years old and you take good care of me.” She looked at the young boy, wondering what she should tell him. Would he understand? “I am very ill. You have heard on the radio about the disease called AIDS. I have that disease,” she told him. Hilifa was quiet for a few minutes. “Does that mean you will die like Daddy?” “There is no cure for AIDS.”

Hilifa nko kuyenda kushure nawa-nawa. Kapi a vhulire kukupakera nka a danaghuke ndi a yende navaghunyendi kayendanga navo. “Vinke vina limbo po?” Ava mu pira. Ene ngoli Hilifia kapi alimburulire, nkango davawina tupu dina kungcoroka Kumari ghendi, “kwato kuveruka. Kwadto kuveruka.” Weni nga ku pakera mbiri ntjeneshi ngava dohoroke vawina, a kudivikilire. Kuni oko nga wananga vimaliva vya ndya?

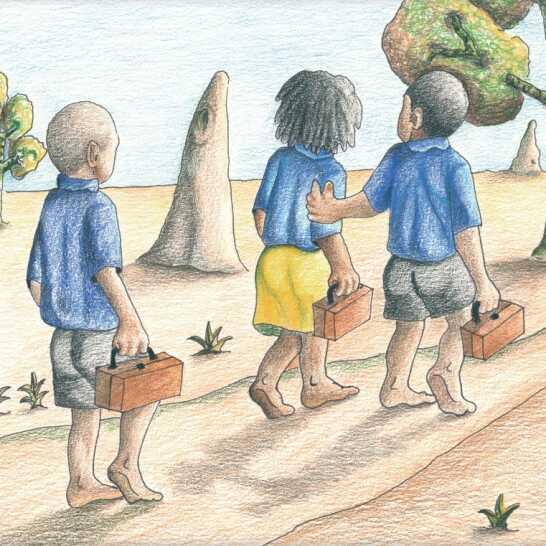

Hilifa walked to school thoughtfully. He couldn’t join in the chatter and games of his friends as they walked along. “What’s wrong?” they asked him. But Hilifa couldn’t answer, his mother’s words were ringing in his ears, “No cure. No cure.” How could he look after himself if his mother died, he worried. Where would he live? Where would he get money for food?

Hilifa a shungiri kuntjishe yendi. A vyukuruka kupitita nyara yendi mumufa washipirangi shakutaghuka, “Kwato kuveruka. Kwato kuveruka.” “Hilifia? Hilifia, kumwe natwe una kara ndi?” Hilifia a kankuka. Mushongikadi Nelao kwaya yimanine kumeho yendi. “Shapuka Hilifia, weno omo lina kara lipuro lyande? Hilifia a kurumana a kengere kumpadi dendi.” “Kapi u wana po lilimbururo palivo opo!” A twikiri kughamba. “Magano, mu tatantere lilimbururo Hilifia.” Hilifia a kuyuvire ntjoni-ntjoni, mushongikadi Nelago nda a mu harukire.

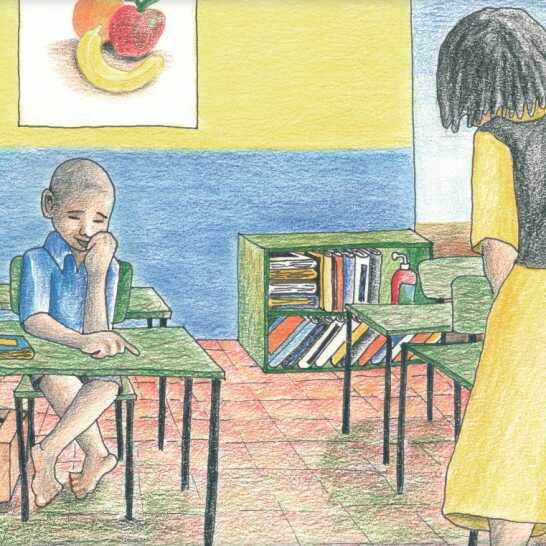

Hilifa sat at his desk. He traced the worn wood markings with his finger, “No cure. No cure.” “Hilifa? Hilifa, are you with us?” Hilifa looked up. Ms. Nelao was standing over him. “Stand up Hilifa! What was my question?” Hilifa looked down at his feet. “You won’t find the answer down there!” she retorted. “Magano, tell Hilifa the answer.” Hilifa felt so ashamed, Ms. Nelao had never shouted at him before.

Hilifa kapitanga muudido pangurangura. Parufugho kashungiranga munkondashongero. “Tjutju nakuyuva mulipumba,” mo kakonganga vaholi vendindi. Kapi kava katanga vipempa vyavinene, kapi kaveranga, ntani nashinka shendi shamaghadaro kundunduma mumutwe wendi yira mpuka daugara. Mushongikadi Nelao kamukenganga tupu mushiporepore. Amu pura ashi udito munke a kalire nagho. “Kwato” a limburura. Matwi ghendi ayuvire kughaya na likudivikiro muliywi yendi. Mantjo ghendi a monine ghoma ogho a kambadalire kuhoreka.

Hilifa struggled through the morning. At break time he sat in the classroom. “I have a stomach ache,” he lied to his friends. It wasn’t a big lie, he did feel sick, and his worried thoughts buzzed inside his head like angry bees. Ms. Nelao watched him quietly. She asked him what was wrong. “Nothing,” he replied. Her ears heard the tiredness and worry in his voice. Her eyes saw the fear he was trying so hard to hide.

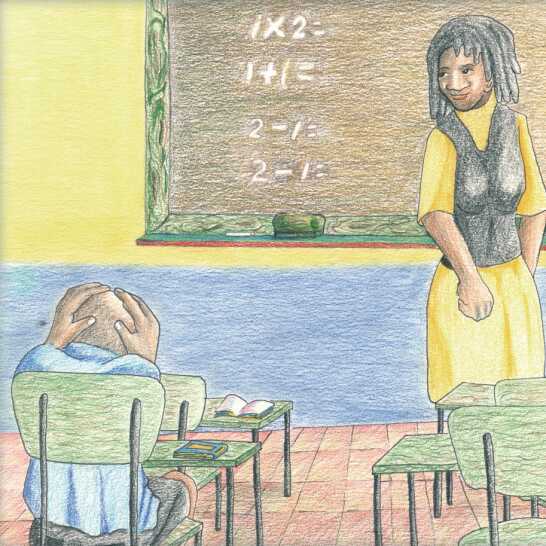

Opo a shetekire Halifa kurughana virughana vyendi vyavivarero nomora adi kuposho mumutwe wendi. Kapi a vhulire kuditulika a divarure nawa. Kadidi tupu makura a kutapa. A vuruka nakughayara vawina. Nyara dendi adi vareke kufaneka magjayadaro ghendi. A faneke vawina mumbete yavo. A kufaneke mwene ana yimana kuntere yambira yavawina. “Mukengeli wamuvaru, pongayika mbapira nadintje,” a ghamba mushongikadi Nelao. Hilifa ntani ngoli ana kumona mafano mumbapira yendi nko kukambadara ashi a taghuremo penapepa yinya, ene ngoli a hulilire unene. Mukengeli a ghupu nakutwara mbapira dinya kwamushongikadi Nelao.

When Hilifa tried to do his maths the numbers jumped around in his head. He couldn’t keep them still long enough to count them. He soon gave up. He thought of his mother instead. His fingers began to draw his thoughts. He drew his mother in her bed. He drew himself standing beside his mother’s grave. “Maths monitors, collect all the books please,” called Ms. Nelao. Hilifa suddenly saw the drawings in his book and tried to tear out the page, but it was too late. The monitor took his book to Ms. Nelao.

Mushingikadi Nelao a kenge pavyo a fanayikire. Opo va rypaghukire vanuke vayendayende kumandi makura a muyita, “Hilifa yiya kuno. Na shana nighambe nove.” Udito munke una karo po?” A mu pura naliywi lyakughomoka. “Vanane kuna kuvera. Kava ntatntere ashi vakara na AIDS. Ngava fa ndi?” “Kapi niyiva, Halifa, ene ngoli kuna kuvera unene ntjeneshi vana kara na AIDS. Kundereko kuveruka. “Nkango odo nka,” nakuverukashi. “Hilifa a vareke kulira. Kayende kumundi, Hilifa,” a ghamba. “Ngnaiya vadingurako nganiya va dingureko vanyoko.”

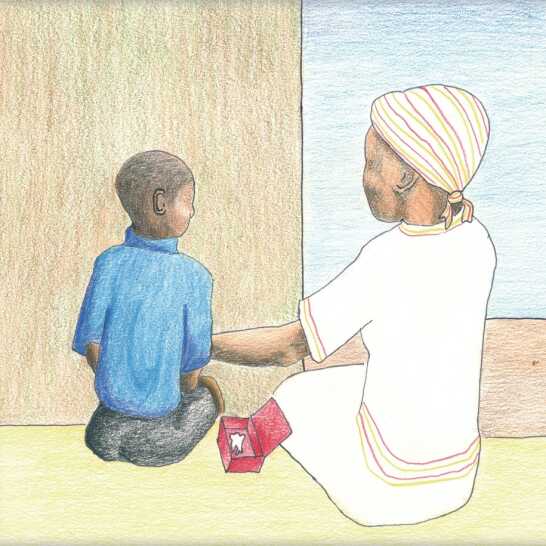

Ms. Nelao looked at Hilifa’s drawings. When the children were leaving to go home she called, “Come here Hilifa. I want to talk to you.” “What’s wrong?” she asked him gently. “My mother is ill. She told me she has AIDS. Will she die?” “I don’t know, Hilifa, but she is very ill if she has AIDS. There is no cure.” Those words again, “No cure. No cure.” Hilifa began to cry. “Go home, Hilifa,” she said. “I will come and visit your mother.”

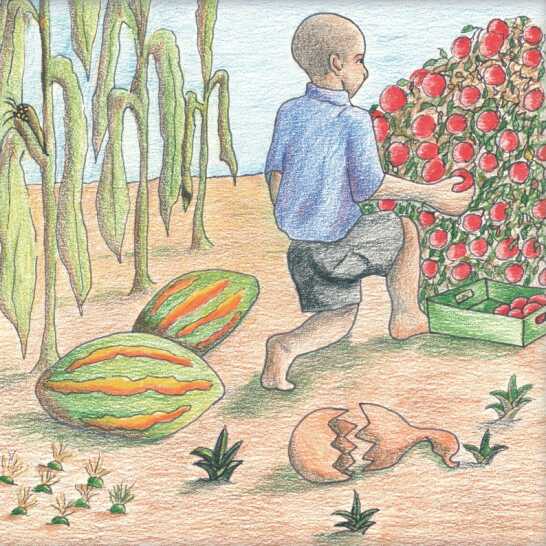

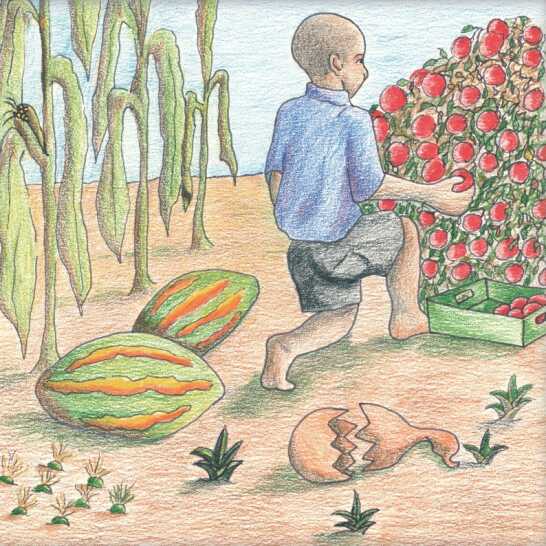

Hilifa a yendi kumundi a kawana vawina kuna kitereka muyusha. “Na nakuterekere muyusha namuntji, Hilifa, ene ngoli na roroka shiri unene. Pakera mbiri kapata kalividi ntani u tware ko madamate ghamwe kushitora. Kuva kaghatughilitira.” Muruku rwa muyusha Hilifa ayendi mushipata shalividi. A kenge kuruvara rwakurwedima rwa livid, madate ghamageha nandungu, makunde ghamare ghashimamahako na spinatji gha shinamaghako shaushovagani, mahako ghashimahako ghakavandja na lipungu lyalire lyashinaghungorodo. A tekere mushipata makura a damuna ntjako yaluyura yamadate ghakupya a tware kushitora. “Vinke ngavi shoroko kushipata shavo ntjeneshi vawina ngava dohoroke?” A ghayadara.

Hilifa went home and found his mother preparing lunch. “I’ve cooked for you today, Hilifa, but now I am very tired. Look after the vegetable garden and take some tomatoes to the shop. They will sell them for us.” After lunch Hilifa went to the vegetable plot. He looked at the bright colours of the vegetables, bright red tomatoes and chillies, long green beans and dark green spinach, the green leaves of the sweet potato and tall golden maize. He watered the garden and picked a bag full of ripe red tomatoes to take to the shop. “What would happen to their garden if his mother died?” he wondered.

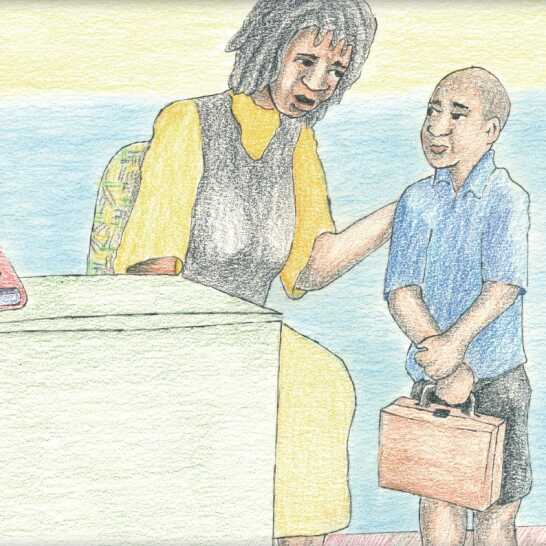

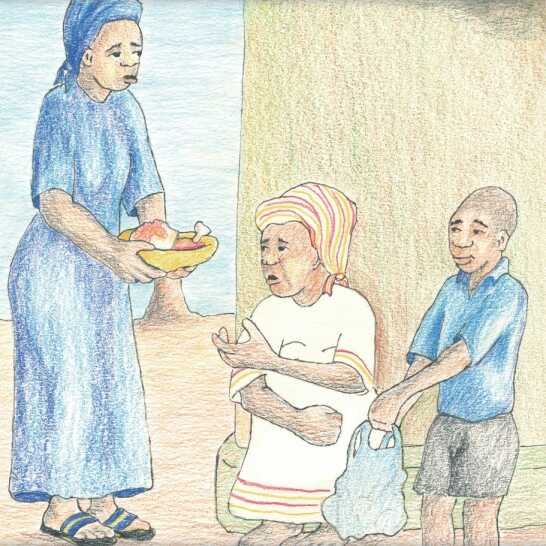

Mushongikadi Nelao aya tiki wangu kuruku opo ayendire Hilifa. A ghupire shirugho shashire mukugambagtura navawina. A pura vawina vaHilifa, “Vanane Ndapanda, kuna kuna kunwanga mutondo wenu waAIDS ndi?” “Kutunda opo a dihoroka nturaghumbo yande na kara nantjoni yakuyenda nka kuvandokotora,” a va mu tantere mushongikad Nelao. “Ame kwa huguvara ashi kapi na ghukaghura uvera. Opo navalikire kuvera ntani ngoli n ayendire kwandokotora aka ntantera ashi nakuliliri unene. Mutondo kapi nka ngauvhura munkwafa.” Mushongikadi Nelao a tantere vanane Ndapanda ashi vinke vyakurughana mposhi mukuvatera Hilifa.

Ms. Nelao arrived soon after Hilifa left. She spent a long time talking to his mother. She asked Hilifa’s mother, “Meme Ndapanda, are you taking the medicine for AIDS?” “After my husband died I was too ashamed to go to the doctor,” she told Ms. Nelao. “I kept hoping I wasn’t infected. When I became ill and went to the doctor she told me it was too late. The medicine would not help me.” Ms. Nelao told Meme Ndapanda what to do to help Hilifa.

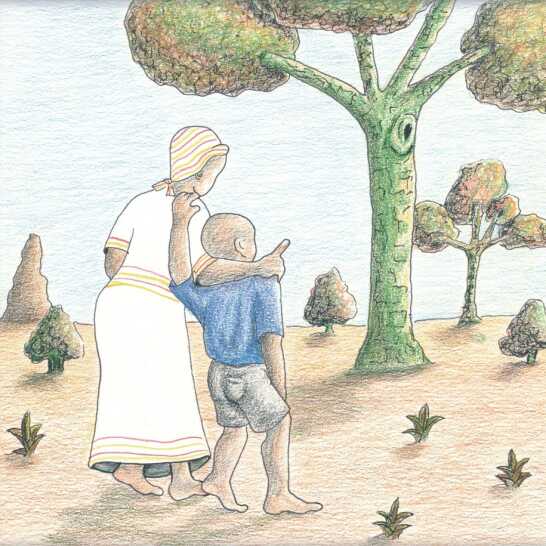

Opo a yire kumundi Halifa vawina a mu pura, “Hilifa, monande, na shana tuyedaurepo. Kuumbatera ndi?” Hilifa a kwaterere livoko lyavawina vavo ava muyeghamene. Ava yendi oko kwa menino vitondo vyamiya vyavire. Ava mu pura, “Una kuvuruka opo kamudanenako mbara yakutanga kuno kumwe nashiro shiye Kunuu? A ghu tanga mbara makura ayikapatamena mumiya. Vasho ava kondjo kuyi mu patumwina mo.”

When Hilifa came home his mother asked him, “Hilifa, my son, I want to take a walk with you. Will you help me?” Hilifa took his mother’s arm and she leaned on him. They walked to where the tall thorn trees grew. She asked him, “Do you remember playing football here with your cousin Kunuu? You kicked the ball into the tree and it got stuck on the thorns. Your father got scratched getting it down for you.”

“Kenaga, shishwa shamandjembere shinya. Kanyange ko ghamwe tupiture kumundi.” Hilifa opo a nyangire ghushuka umwe weno waghutovali, ava ghamba, “Kuna kuvuruka opo wakalire ove shimpe u musheshughona kaunyanda ushuka nantanga dagho damunda. Kapi kaghu yendanga kukashayishe ure washivike nashintje.” “Nhii, lipumba lyande kali kornaga,” A vhuruka Hilifa, uye kuna kushepa.

“Look, there’s an omandjembere bush. Go and pick some to take home.” When Hilifa was picking the sweet berries, she said, “Do you remember when you were small you ate the berries and the seed inside. You didn’t go to the toilet for a week!” “Yes, my stomach was sooo sore,” remembered Hilifa, laughing.

Opo vaka tikire kumundi vawina vaHilifa va rorokire ngundu. Hilifa a yendenyeke tiye. Vanane Ndapanda ava ghupu kambangu kakadidi munda yauro wavo. “Hilifa, oshino shoye. Mushimbangu shino munakara ovyo ngavi kuvatero uyive oko wa tunda.

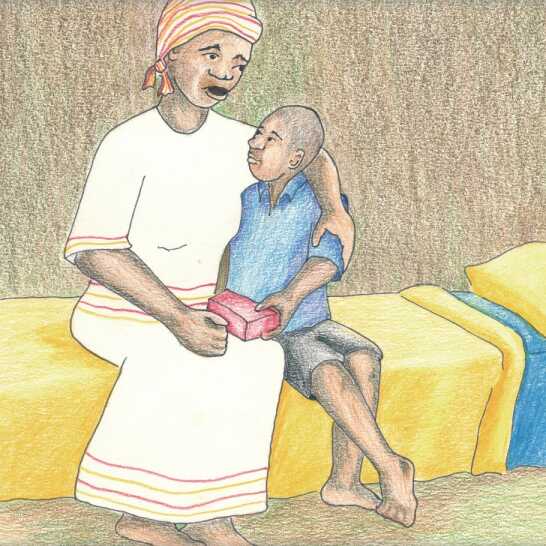

When they got home Hilifa’s mother was very tired. Hilifa made some tea. Meme Ndapanda took a small box from under her bed. “Hilifa, this is for you. In this box are things that will help you remember where you come from.”

Ava ghumbu vingurumba mushimbangu shimwe nashimwe. “olino lifano lyavasho vana kukwaterere. Ove kwalire monarume wendi wambeli. Lifano lino mpopo nakutwalire kuvanyakulypye vaka kumoneko, va hafire shiri unene. Olino ndyo liyegho lyoye lyakuhova olyo wakukire. Kuna kuvuruka ashi weni omo walilire makura ame ani kutwenyidiri ashi shimpe ngaghaya ko ghamwe ghamayingi. Oshino ntjo shiranda vampire vasho opo twalire atwe tuna kara munkwara dendi ure wamwaka umwe tupu.”

She took the mementos out of the box one by one. “This is a photo of your father holding you. You were his firstborn son. This photo is when I took you to see your grandparents, they were so happy. This is the first tooth you lost. Do you remember how you cried and I had to promise you that more would grow. This is the brooch your father gave me when we were married for one year.”

Hilifa a kwaterere shimbangu nko kuvareka kulira. Vawina ava mu kwaterere nko kuraperera, “Karunga ndi a popere kumwe nkukunga.” Vano kuna mukwatere okuno pakughambanga. “Hilifa, monande. Una yiva ashi ame kuna kuvera unene, ntantani tupu ngani wane vasho. Kapi na shana uyune. Kuvuruka shi weni omo na kuhora. Vuruka ashi weno vakuholire vasho.”

Hilifa held the box and began to cry. His mother held him close by her side and said a prayer, “May the Lord protect you and keep you safe.” She held him as she spoke. “Hilifa, my son. You know that I am very ill, and soon I will be with your father. I don’t want you to be sad. Remember how much I love you. Remember how much your father loved you.”

Vawina ava twikiri, “Nkwirikoye Kave ngatu tuminanga maliva ntjeneshi ana vhuru. A ntantera ashi nga kupakera mbiri. Na vi mutantera kare. Ngauyendanga kushure na Kunuu, mondendi. Kunuu kuna kara muntambondunge ya 4 yira ove nka. Ngava kupakera nawa mbiri.” Na hora nkwirikwande Kunuu navangumweyi Muzaa, “A ghamba Hilifa.” Ntani na hora kudanura na Kunuu. Ndi nga mu kara nawa ntjeneshi nga mupakere mbiri? “Hawe, monande. I kapi ngai kara nawa. Ove kumpakera nawa mbiri. Na kara namfumwa muku kara namonde wamuwa ngoweyo.”

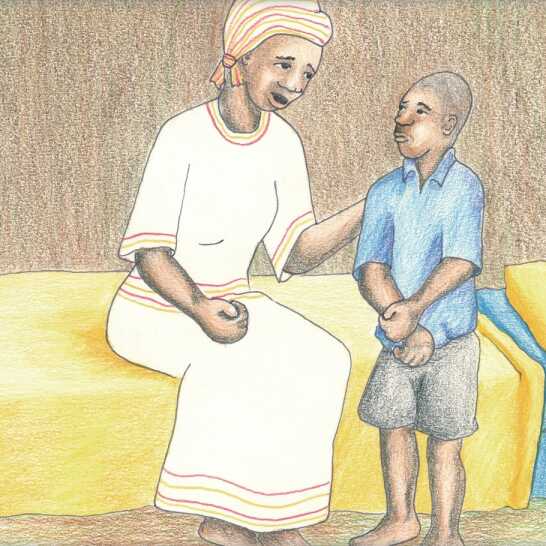

His mother continued, “Uncle Kave from Oshakati sends us money when he can. He told me that he will care for you. I have talked to him about it. You’ll go to school with Kunuu, his son. Kunuu is in Grade 4 like you. They will take good care of you.” “I like Uncle Kave and Aunt Muzaa,” said Hilifa. “And I like playing with Kunuu. Would you become well if they look after you?” “No, my son. I won’t become well. You look after me very well. I am proud to have such a good son.”

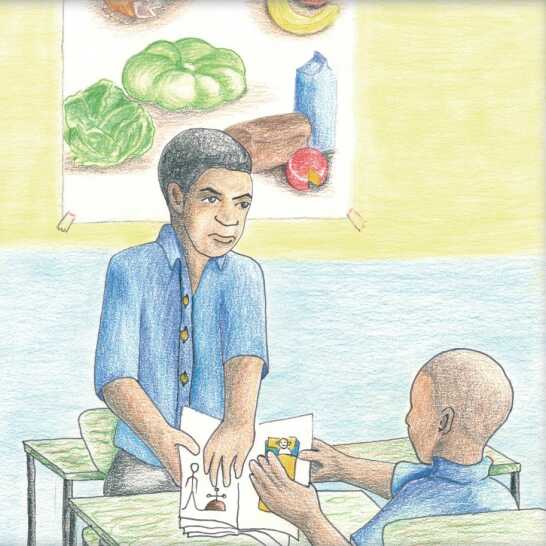

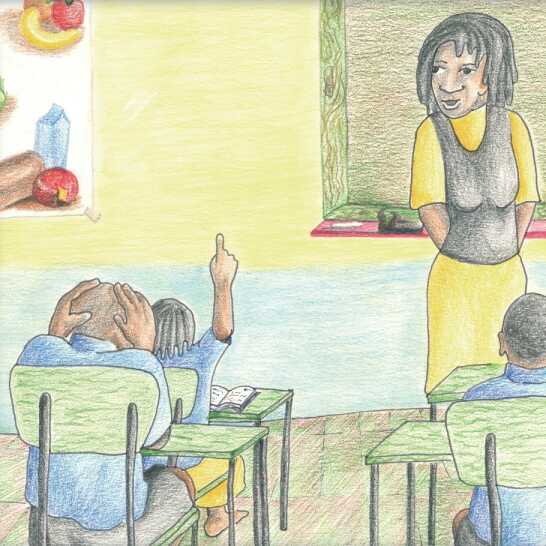

Ngurangura yakukwamako mushongikadi Nelao a shongire vyakuhamena HIV na AIDS. Vanuke vaklire nautjirwe. Vano kwayuvanga uvera uvera uno kuradio, ene ngoli naumweshi kavighamburango mumundi. “Kuni watunda” A pura Magano. “Weni omo twaghuwananga?” A pura Hidipo. Mushongikadi Nelao a fwaturura ashi HIV ne lidina lyakambumburu. Ntjeneshi murwana a kara na kambumburu muhonde yendi shimpe kumoneka mukangure. “Atwe kurenka ashi vana kara na AIDS ntjeneshi ava vareke ngoli kuvera.”

The next morning at school Ms. Nelao taught them about HIV and AIDS. The learners looked afraid. They heard about this illness on the radio, but no-one spoke about it at home. “Where does it come from?” asked Magano. “How do we catch it?” asked Hidipo. Ms. Nelao explained that HIV is the name of a virus. When a person has the HIV virus in their blood they still look healthy. “We say they have AIDS when they become ill.”

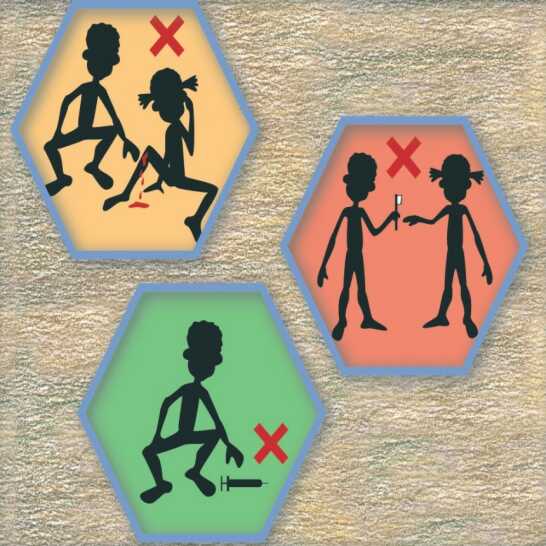

Mushongikadi Nelao a fwaturulire ndjira dimwe dakuvhura kughaura kambumburu. “Ntjeneshi murwana umwe ana kara na kamburumburu ka HIV ndi AIDS kuvhura kuwana kambumburu muhonde yavo. Kapishi kurughanita kavemba oko ana rughanita kare unyoye ndi mukuyaure shitondo shakukuputjita mayegho. Ntjeneshi kua kutomona kumatwi, tuna hepa kurughanita tuvemba oto vatereka muruku rwaku turughanita ndi ndi ntonga. “A fwaturura ashi weni mwakuvuhura kutereka ntonga na tuvemba muruku rwakuturughanita. “Ntjeneshi tuna kuremeke naumwetu kukarapo hinde mposhi tuna hepa kutantera vakurona vakuyure shironda. Tuna kepa kudinga shironda muku shipopera,” ava tantere.

Ms. Nelao explained some of the ways we can be infected with HIV. “If someone has HIV or AIDS we can catch the virus from their blood. We should never share razors or toothbrushes. If we get our ears pierced we must use sterilised blades and needles.” She explained how needles and blades should be sterilised. “If we hurt ourselves and there is blood we must ask an adult to clean the wound. We must cover the wound to protect it,” she told them.

Makura ava negheda lifano. “Odino ndo ndjira odo u pira kuwana HIV,” a va tantere. “Kapi ngau wana HIV pakurughanita kandjugho, ndi kurughanita livango lyakuyoghanena kumwe. Kukumamatera, kukuncumita ndi kukumorora mulivoko na murwana ogho a karo na HIV ndi AIDS shimpe una kara mulipopero. Shimpe viwawa tupu mkurughanira mukwe ndi kulya shisha shisha shimwe na murwana gho ana karo na HIV ndi AIDS. Kapi u vhura kuyi wana kwamurwana pakukotora ndi pakuwetjimita. Ntani nka kapi u kawana pakukushuma mwe ndi pakukushuma vimbumburu peke.”

Then she showed them a chart. “These are all the ways you can’t catch HIV,” she told them. “You won’t get HIV from using the toilet, or sharing a bath. Hugging, kissing or shaking hands with someone with HIV or AIDS is also safe. It’s OK to share cups and plates with someone who has HIV or AIDS. And you can’t catch it from someone who is coughing or sneezing. Also, you can’t get it from mosquitoes or other biting insects like lice or bedbugs.”

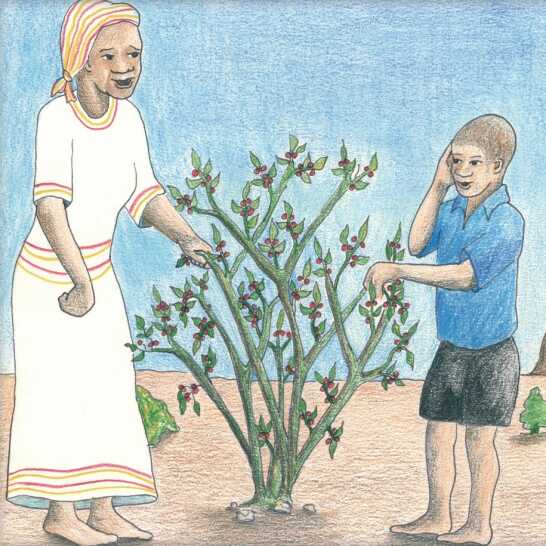

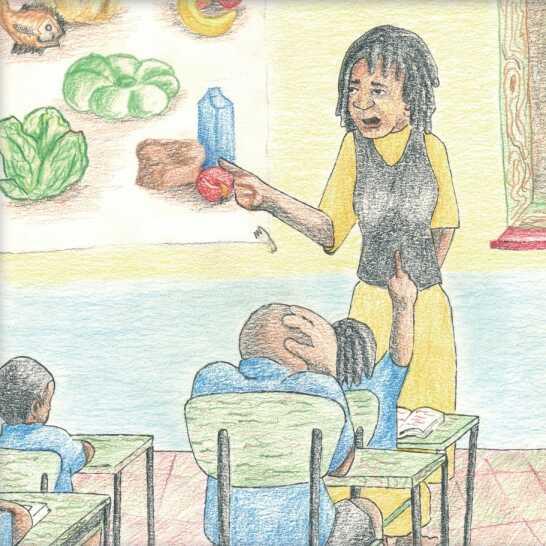

“Vinke vyakurughana ntjeneshi una kawana?” A pura Magana. “Yaro, una hepa ngoli kukupangera mbiri ntani una hepa kulya ndya daukenaguki. Kenga pano palifano lyentu lyandya,” a ghamba. “Are ana kuvuruko ashi ndya munke dadiwa koye?” A pura.

“What do you do if you’ve got it?” asked Magano. “Well, you must take care of yourself and eat lots of healthy food. Look at our food chart,” she said. “Who can remember what food is good for you?” she asked.

Opo aka tikire kumundi Hilifa a aka tantera vawina ovyo ana kakushongire kushure liyuva linya. “Mushongikadi Nelao ana katushonga vya kuhamena ku HIV na AIDS ntani weni mwakupakera mbiri murwana ogho ana kuvero. Magano na Hidipo kuvaya mbaterako kurughana virughana vyande mumundi ntani shimpe nka kutuya rughana kumwe virughanatapo vyetu vyakushure,” ava tantere.

When Hilifa got home he told his mother what he had learned at school that day. “Ms. Nelao told us about HIV and AIDS and how to look after someone who’s ill. Magano and Hidipo are going to help me with my chores and we will do our homework together,” he told her.

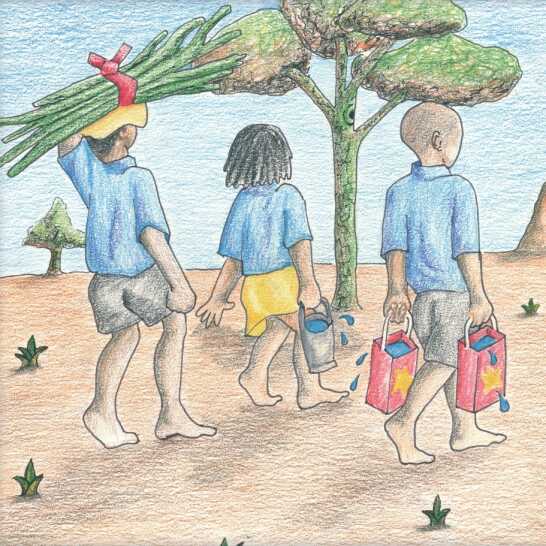

Shitengeyuva shinya Mgano aya vayere Hilifa kuveta mema. Hidipo amu vatere kukatjava vikuni. Ava shungiri mumndulye waugongo kumwe nakurughana virughanatapo vyavo vyakushure.

That afternoon Magano came and helped Hilifa to fetch water. Hidipo helped him to gather firewood. Then they sat and did their homework in the shade of the marula tree.

Mushongikadi Nelao naye nka a tentere vamabarambo va Hilifa ashi kuna kupakera mbiri vawina. Va mu huguvalitire kumuvatera. Kehe ngurova mumaparambo peke kayanga nandya dadipyu mposhi vaya lye. Hilifa kehe pano kavapanga lividi lyamushipata shavo.

Ms. Nelao had also told Hilifa’s neighbours that he was looking after his mother. They had promised to help him. Every night a different neighbour came with hot food for them to eat. Hilifa always gave them some vegetables from the garden.

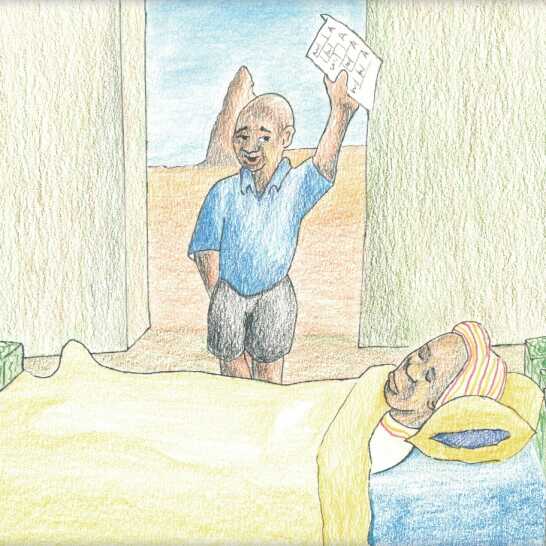

Liyuva lyakuhulilira lyashure mushuvaka Hilifa a hafire unene. A duka ayende kumundi aka neghede vawina ndjapo yendi. A duka dogoro mulirapa kumwe nakuyiyira, “yina, yina. Kenge nu ndjapo yende. Na wana ‘A’, ‘A’, ntani ‘A’ dadiyingi.” Hilifa kwaya wanine vawina vana gharama paghuro. “Yina!” A yiyiri. “Yina! Rambukenu!” Kapi va vhulire kurambuka.

On the last day of the school term Hilifa was very happy. He ran home to show his mother his report card. He ran into the yard calling, “Mum. Mum. Look at my report card. I have got ‘A’, ‘A’, and more ‘A’s’.” Hilifa found his mother lying in bed. “Mum!” he called. “Mum! Wake up!” She didn’t wake up.

Hilifa a dukiri kuvamaparambo. “Vanane. Vanane. Kapi vana rambuka,” a liri. Vamaparambo ava yendi kumundi naHalifa ava kawana ashi vanane Ndapanda mumbete yavo.” Vana dohoroka, Hilifa,” ava ghamba naruguvo.

Hilifa ran to the neighbours. “My Mum. My Mum. She won’t wake up,” he cried. The neighbours went home with Hilifa and found Meme Ndapanda in her bed. “She is dead, Hilifa,” they said sadly.

Mbudi ayi kuhana wangu-wangu ashi vanane Ndapanda vana dohoroka. Mumundi amuya yura ngoli valikoro, vamaparambo vanaholi. Ava raperere ngoli vawina vaHalifa kumwe kuyimba ntjumo. Ava ghambaura ngoli kuhamena vyaviwa kutwara omo va mu yivire.

Very quickly the news spread that Meme Ndapanda was dead. The house was full of family, neighbours and friends. They prayed for Hilifa’s mother and sang hymns. They talked about all the good things they knew about her.

Vananeghona Muzaa shana vagenda navantje. Nkwirikwendi Kave a tantere Hilifa ashi ngava mu pitura ngava yende kuOshakati muruku rwalitamu. Vanyakulyendi vavakafumu ava mu timwiti shitimwitira shakuhamena kuvawina opo vakalire ashi vavo shimpe vakadona.

Aunt Muzaa cooked for all the visitors. Uncle Kave told Hilifa that they would take him back to Oshakati after the funeral. His Grandfather told him stories about his mother when she was a little girl.

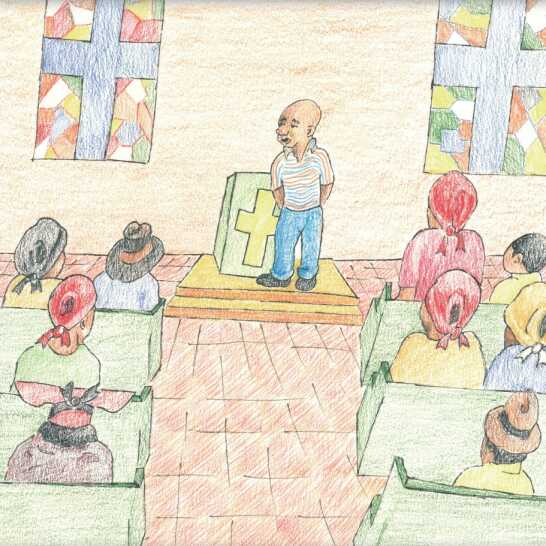

Palitamu Hilifia a yendi munkirishe Hilifia a yendi kumeho a tantere mbunga vyakuhama kuvawina. “Vanane vaholire ntani nka ntekulire nawa. Kava ntanteranga ashi ni dameke kukushonga mposhi ngani Kawane virughana vyaviwa. Vantjaninine ruhafo. Ngani dameka kukushonga nakudameka kurughana mposhi ngava kuyuva mfumwa.”

At the funeral Hilifa went to the front of the church and told everyone about his mother. “My mother loved me and looked after me very well. She told me to study hard so that I could get a good job. She wanted me to be happy. I will study hard and work hard so that she can be proud of me.”

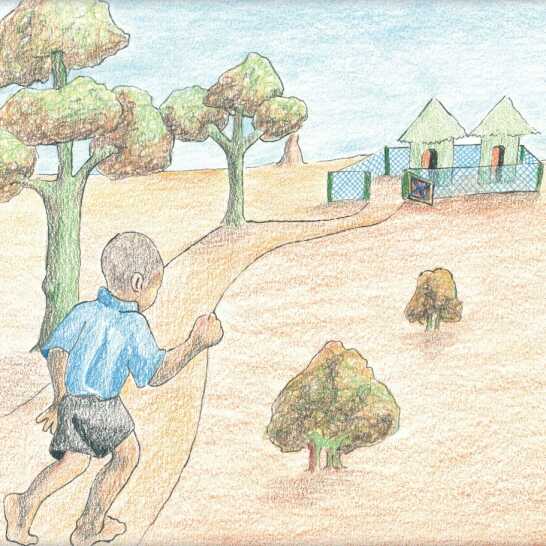

Muruku rwalitamu nkwikwendi Kave navawinaghona Muzaa va mu vatilire Hilifia kurongera vininke vavitware kuOshakati. Kunuu, kwa tatililire shankondo-mumukara na muholi wendi wamupe, “Va mu tantilire.” Nga tu kupangarera mbiri yira monarume wanaghumwetu. “Hilifia a shuvu ngoli mundi unya nko kukaronda kumwe navo mushihauto.”

After the funeral Uncle Kave and Aunt Muzaa helped Hilifa to pack his things to take to Oshakati. “Kunuu is looking forward to having a new friend,” they told him. “We will care for you like our own son.” Hilifa said goodbye to the house and got into the taxi with them.

Written by: Kandume Ruusa, Sennobia-Charon Katjiuongua, Eliaser Nghitewa

Illustrated by: Jamanovandu Urike

Translated by:

Language: Rumanyo

Level: Level 5

Source: Orphans need love too from African Storybook

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.