Eefiye nado oda pumbwa ohole Orphans need love too

Kandume Ruusa, Sennobia-Charon Katjiuongua, Eliaser Nghitewa

Kandume Ruusa, Sennobia-Charon Katjiuongua, Eliaser Nghitewa

Jamanovandu Urike

Jamanovandu Urike

Oshikwanyama

Oshikwanyama

Level 5

Level 5

The audio for this story is currently not available.

The audio for this story is currently not available.

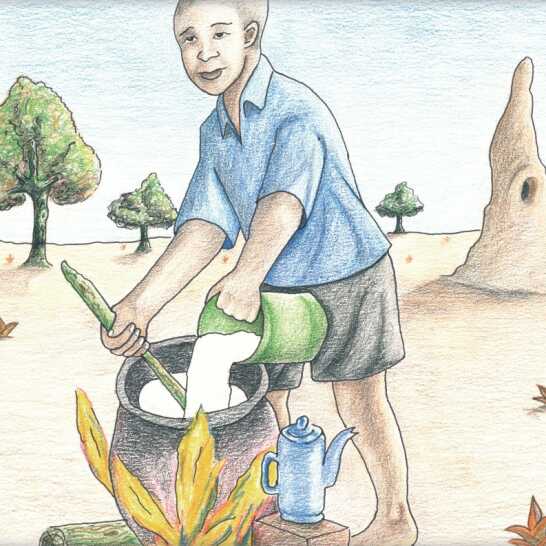

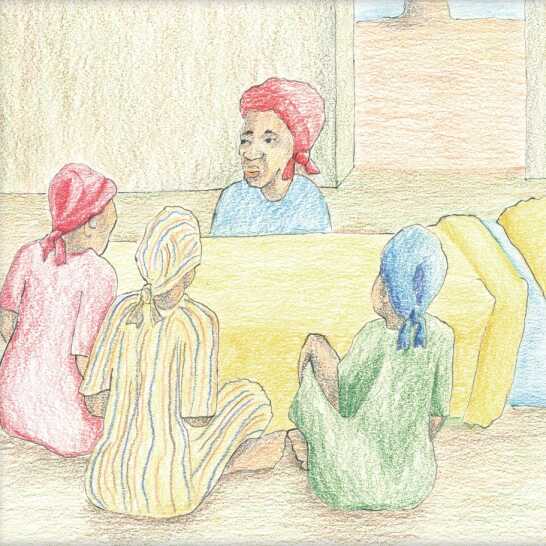

Ongula keshe Hilifa oha penduka diva opo a ka longekide oshuumbululwa shaina. Ina okwa kala efimbo lile ta vele. Hilifa okwe lihonga okufila ina oshisho naye mwene. Hilifa okwa kala ha ningile ina otee (okafe) eshi iha dulu vali okupenduka. Oha twaalele ina otee noku mu telekela oshimbobo. Omafimbo amwe ina okwa kala a nghundipala ita dulu okulya. Hilifa okwa kala a limbililwa kombinga yaina. Xe okwa fya nale eedula mbali da pita, ndele paife ina oye vali ou ta vele unene. Ina okwa li a utama naanaa ngaashi xe.

Every morning Hilifa woke up early to prepare breakfast for his mother. She had been sick a lot recently and Hilifa was learning how to look after his mother and himself. When his mother was too ill to get up he would make a fire to boil water to make tea. He would take tea to his mother and prepare porridge for breakfast. Sometimes his mother was too weak to eat it. Hilifa worried about his mother. His father had died two years ago, and now his mother was ill too. She was very thin, just like his father had been.

Ongula yefiku limwe okwa pula ina ta ti, “Oshike hano meme? Onaini to ti po xwepo? Iho teleke vali. Iho dulu vali okulonga mepya ile okuwapaleka eumbo. Iho longekidile nge vali okabaki kange koikulya ile u koshe omudjalo wange wofikola…” “Hilifa mumati wange, u na ashike eedula omugoi, mumati wange, ndele oho file nge nawa oshisho.” Ta tale nawa omonamati ehe shii kutya ote mu lombwele shike. Ota udu ko ngoo mbela? “Ame ohandi vele. Owa uda moradio kutya ope na omukifi oo hau ifanwa oAIDS. Ame ondi na omukifi oo,” osho emu lombwela. Hilifa okwa kala a mwena manga okafimbo. “Tashi ti kutya naave oto fi ngaashi tate?” “Kape na eveluko komukifi woAIDS.”

One morning he asked his mother, “What is wrong Mum? When will you be better? You don’t cook anymore. You can’t work in the field or clean the house. You don’t prepare my lunchbox, or wash my uniform…” “Hilifa my son, you are only nine years old and you take good care of me.” She looked at the young boy, wondering what she should tell him. Would he understand? “I am very ill. You have heard on the radio about the disease called AIDS. I have that disease,” she told him. Hilifa was quiet for a few minutes. “Does that mean you will die like Daddy?” “There is no cure for AIDS.”

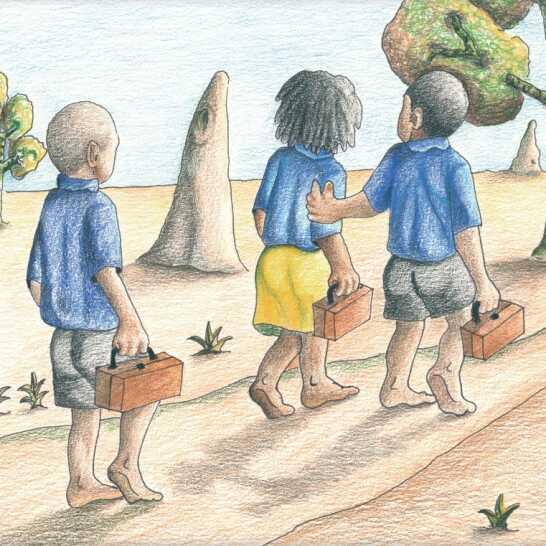

Hilifa okwa ya kofikola. Iha dulu okupopya ile okudanauka nawa pamwe navakwao. “Oshike hano?” tave mu pula. Ashike Hilifa ka li ta dulu okunyamukula, eshi tashi kwelengedja momatwi aye, oitya yaina, “Ihau veluka. Ihau veluka.” Ote ke lifila mbela oshisho ngahelipi ngeenge ina a fi, a limbililwa. Ota ka kala peni? Ota ka hanga peni oimaliwa yoikulya? Hilifa walked to school thoughtfully. He couldn’t join in the chatter and games of his friends as they walked along. “What’s wrong?” they asked him. But Hilifa couldn’t answer, his mother’s words were ringing in his ears, “No cure. No cure.” How could he look after himself if his mother died, he worried. Where would he live? Where would he get money for food?

Hilifa walked to school thoughtfully. He couldn’t join in the chatter and games of his friends as they walked along. “What’s wrong?” they asked him. But Hilifa couldn’t answer, his mother’s words were ringing in his ears, “No cure. No cure.” How could he look after himself if his mother died, he worried. Where would he live? Where would he get money for food?

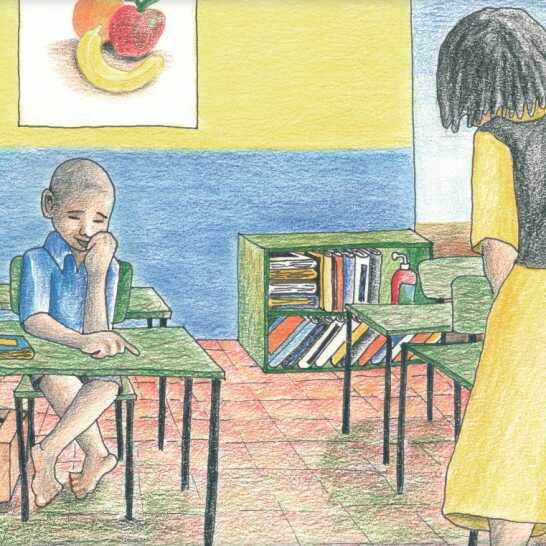

Hilifa ta kala omutumba pokataafula kaye. Ta nyotaanyota oshitaafula ye ta diladila, “Ihau veluka, ihau veluka.” “Hilifa, Hilifa, ou li ngoo pamwe nafye hano?” Hilifa ta petuka. Mee Nelao okwe mu fikamena. ‘’Hilifa fikama! Onda ti ngahelipi?” Hilifa okwa tala peemhadi daye. “Ito mono enyamukulo opo to tale! Magano, lombwela Hilifa enyamukulo.” Hilifa okwa li a fya ohoni shaashi, mee Nelao ka li e mu hanyaukila nale ngaho.

Hilifa sat at his desk. He traced the worn wood markings with his finger, “No cure. No cure.” “Hilifa? Hilifa, are you with us?” Hilifa looked up. Ms. Nelao was standing over him. “Stand up Hilifa! What was my question?” Hilifa looked down at his feet. “You won’t find the answer down there!” she retorted. “Magano, tell Hilifa the answer.” Hilifa felt so ashamed, Ms. Nelao had never shouted at him before.

Hilifa ka li te shi endifa nawa ongula. Pefimbo lokafudo okwa kala e li omutumba mongulu. “Ohandi vele medimo,” ta fufya ookaume kaye. Ashike kasha li oipupulu, unene okwa li ngoo ta vele shili opamwe nelimbililo. Mee Nelao ote mu tongolola kanini nakanini. Okwe mu pula kutya oshike sha puka. “Kape na sha,” Hilifa ta nyamukula. Omatwi aye okwa uda eloloko nelimbililo mondaka yaye. Omesho aye okwa mona outile oo kwali ta kendabala neenghono okuholeka.

Hilifa struggled through the morning. At break time he sat in the classroom. “I have a stomach ache,” he lied to his friends. It wasn’t a big lie, he did feel sick, and his worried thoughts buzzed inside his head like angry bees. Ms. Nelao watched him quietly. She asked him what was wrong. “Nothing,” he replied. Her ears heard the tiredness and worry in his voice. Her eyes saw the fear he was trying so hard to hide.

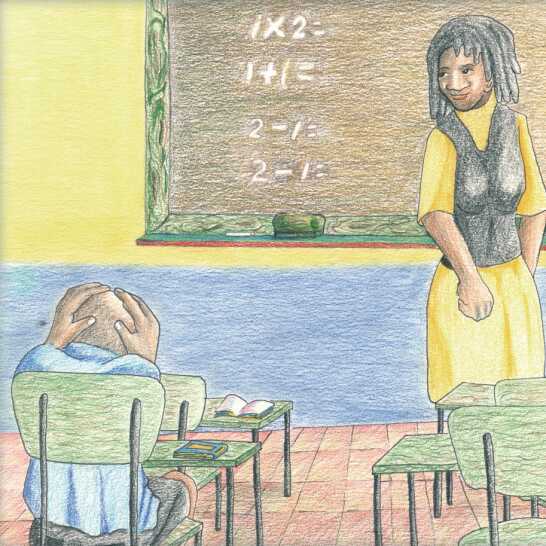

Hilifa eshi kwa li ta kendabala okuvala omuvalu, eenomola oda li tadi tanauka momutwe waye. Ita dulu okutwikila okuvalula nokonima ina hala vali. Ponhele yaasho okwa kala ta dilaadila ina. Okwa hovela okufaneka ina eshi e li mombete. Ote lifaneke a fikamena ombila yaina. “Omwoongeli woilonga yomuvalu, kwafe nge u ongele omambo aeshe,” osho mee Nelao a ti meendelelo. Hilifa okwa mona osho a faneka membo laye, ndee ta kendabala ngeno a pombole mo efano, ashike efimbo ola pwa ko. Omwoongeli womambo okwa twala nale embo kumee Nelao.

When Hilifa tried to do his maths the numbers jumped around in his head. He couldn’t keep them still long enough to count them. He soon gave up. He thought of his mother instead. His fingers began to draw his thoughts. He drew his mother in her bed. He drew himself standing beside his mother’s grave. “Maths monitors, collect all the books please,” called Ms. Nelao. Hilifa suddenly saw the drawings in his book and tried to tear out the page, but it was too late. The monitor took his book to Ms. Nelao.

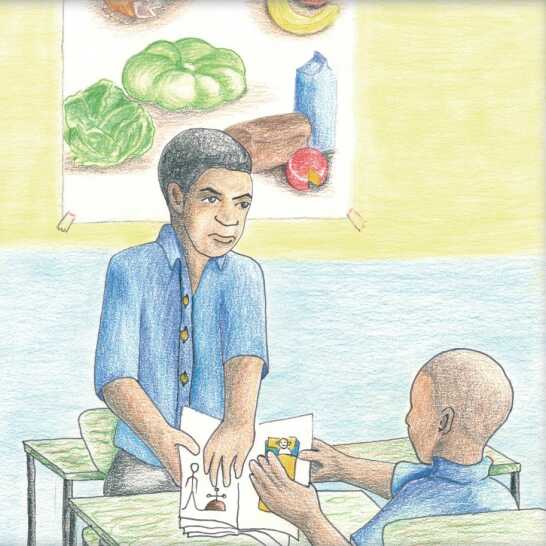

Mee Nelao ta tale osho sha fanekwa kuHilifa. Eshi ounona tava i komaumbo, okwa ufana Hilifa. “Hilifa ila kwaame, onda hala ndi popye naave.” “Oshike sha puka?” mee Nelao ta pula. “Meme ota vele, okwa lombwela nge kutya oku na oAIDS. Ota fi?” “Kandi shi shii Hilifa, ashike nge mboli oku na ombuto ota vele kape na ouhaku wayo.” Oitya oyo, “Ita veluka. Ita veluka.” Oya kwenifa Hilifa. “Inda keumbo, Hilifa” mee Nelao ta ti,” Ohandi ya ndi talele po meme woye.”

Ms. Nelao looked at Hilifa’s drawings. When the children were leaving to go home she called, “Come here Hilifa. I want to talk to you.” “What’s wrong?” she asked him gently. “My mother is ill. She told me she has AIDS. Will she die?” “I don’t know, Hilifa, but she is very ill if she has AIDS. There is no cure.” Those words again, “No cure. No cure.” Hilifa began to cry. “Go home, Hilifa,” she said. “I will come and visit your mother.”

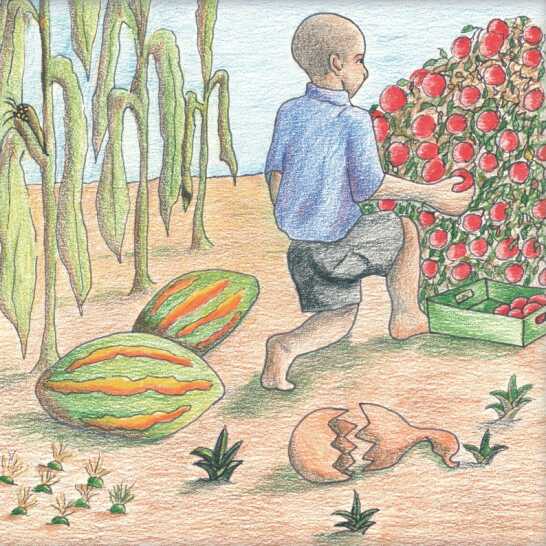

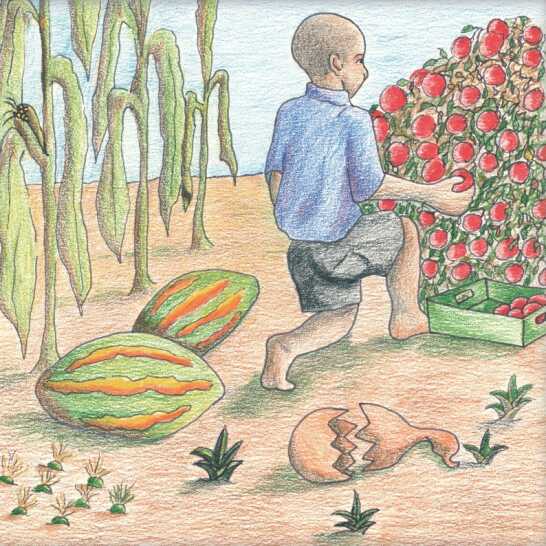

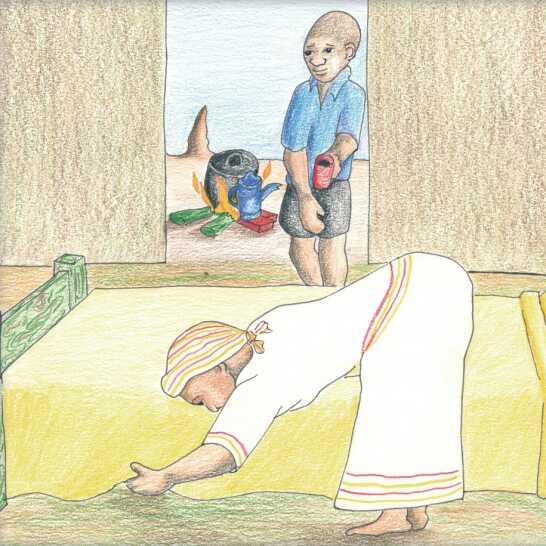

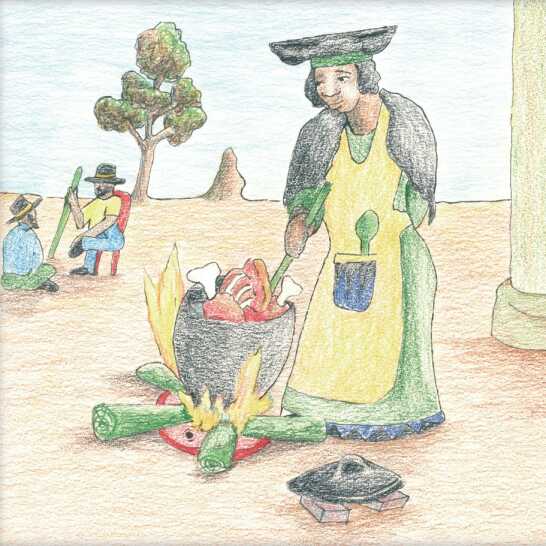

Hilifa eshi e uya meumbo okwa hanga ina ta longekida omusha. “Onde ku telekela nena Hilifa, ashike paife onda loloka. Tonatela oshikunino shoikwambidi ndele to kufa omanyoto u twale kofitola. Otave ke tu landifila.” Konima yomusha, Hilifa okwa ya koshikunino. Okwa tala komaluvala a hapa nawa oikwambidi, nomanyoto a tilyana nawa neendungu, omakunde male a ngelina nawa nombidi yospinasi, omafo a ngelina nawa oihakautu nomapungu. Okwa tekela oshikunino ndee ta tona ondjato i yadi omanyoto ndele te a twala kofitola. “Oshikunino shavo otashi ka kala ngahelipi mbela ngeenge ina okwa fi?” osho te lipula.

Hilifa went home and found his mother preparing lunch. “I’ve cooked for you today, Hilifa, but now I am very tired. Look after the vegetable garden and take some tomatoes to the shop. They will sell them for us.” After lunch Hilifa went to the vegetable plot. He looked at the bright colours of the vegetables, bright red tomatoes and chillies, long green beans and dark green spinach, the green leaves of the sweet potato and tall golden maize. He watered the garden and picked a bag full of ripe red tomatoes to take to the shop. “What would happen to their garden if his mother died?” he wondered.

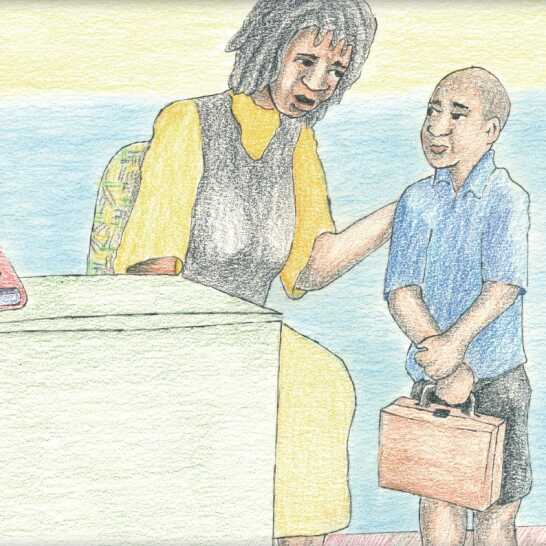

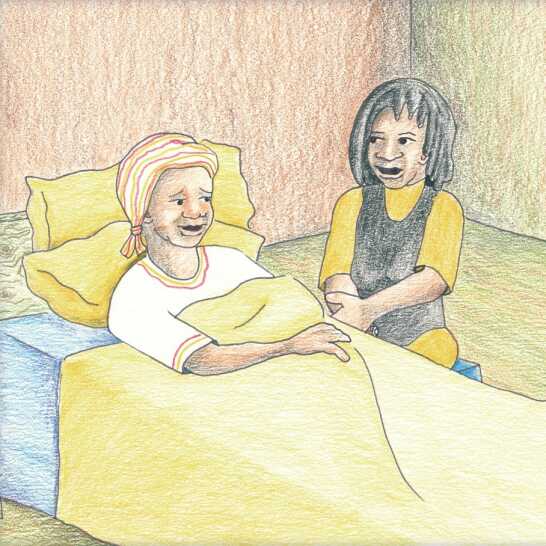

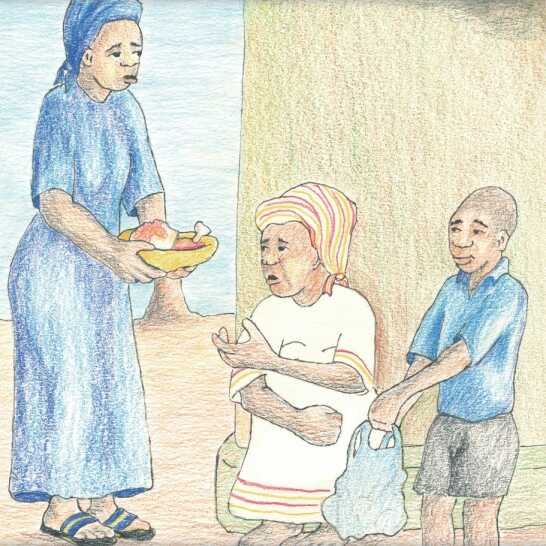

Mee Nelao okwa fika diva eshi Hilifa a ya. Okwa kala efimbo lile ta popi nameme waHilifa. Te mu pula, “Meme Ndapanda, oho nu tuu omiti doAIDS?” “Konima eshi omushamane wange a fya, onda kala nda fya ohoni okuya kundokotola,” ta lombwele mee Nelao. “Onde lipula kutya pamwe inandi kwatwa ngaa kombuto. Eshi nda tameka okuyehama ndele handi i ku ndokotola, okwa lombwela nge kutya efimbo ola pwa po. Omiti itadi kwafa nge vali.” Mee Nelao okwa lombwela meme Ndapanda osho e na okuninga a kwafele Hilifa.

Ms. Nelao arrived soon after Hilifa left. She spent a long time talking to his mother. She asked Hilifa’s mother, “Meme Ndapanda, are you taking the medicine for AIDS?” “After my husband died I was too ashamed to go to the doctor,” she told Ms. Nelao. “I kept hoping I wasn’t infected. When I became ill and went to the doctor she told me it was too late. The medicine would not help me.” Ms. Nelao told Meme Ndapanda what to do to help Hilifa.

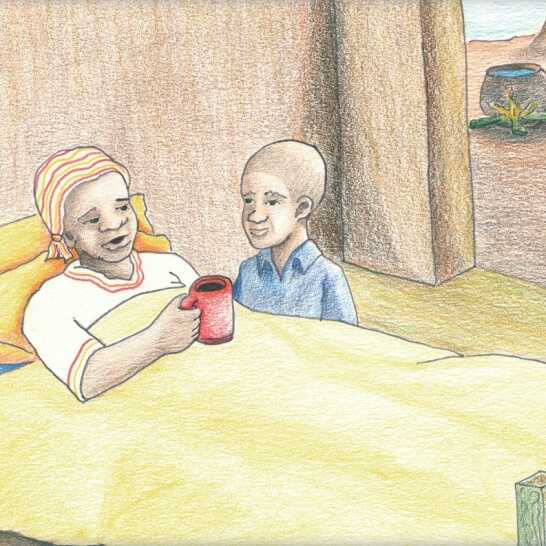

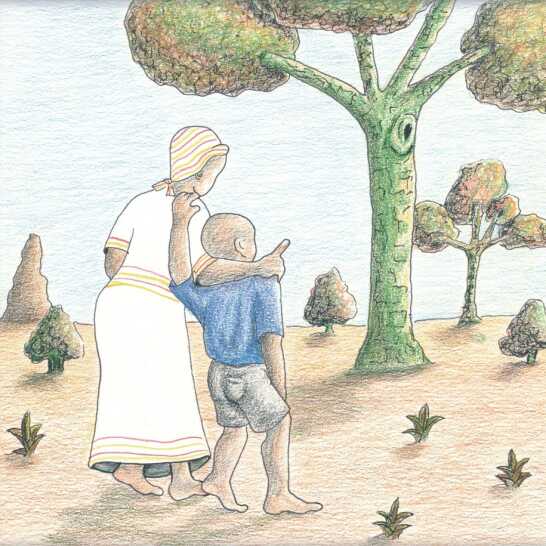

Eshi Hilifa e ya keumbo meme Ndapanda okwe mu pula ta ti, “Hilifa mumati wange, onda hala tu ka ende naave. Oto kwafele nge?” Hilifa ta kwata ina mokwooko opo a shiive a yaamene kuye. Ova ya fiyo openo la kula, “Oto dimbulukwa ngoo fiku mwa li tamu denge okatanga naKunuu? Owa lyatele okatanga ndee taka hakele meno omo. Xo okwa kwenyununinwe komakiya eshi e ke mu kufila mo.”

When Hilifa came home his mother asked him, “Hilifa, my son, I want to take a walk with you. Will you help me?” Hilifa took his mother’s arm and she leaned on him. They walked to where the tall thorn trees grew. She asked him, “Do you remember playing football here with your cousin Kunuu? You kicked the ball into the tree and it got stuck on the thorns. Your father got scratched getting it down for you.”

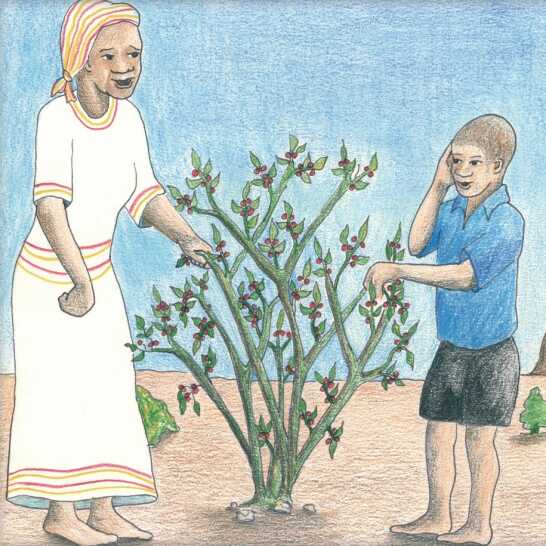

“Tala, oixwa yomandjebele. Inda u ka tone ko amwe u twaalele keumbo.” Eshi Hilifa kwa li ta tona omadjebele, ina okwe mu pula, “Oto dimbuluka eshi wa li u munini, owa li ho li eembe noiti yado. Owa kala oule woshivike ino ya koixwa.” “Eheeno, edimo lange ola li li udite oudjuu,” Hilifa teshi dimbuluka ta yolo.

“Look, there’s an omandjembere bush. Go and pick some to take home.” When Hilifa was picking the sweet berries, she said, “Do you remember when you were small you ate the berries and the seed inside. You didn’t go to the toilet for a week!” “Yes, my stomach was sooo sore,” remembered Hilifa, laughing.

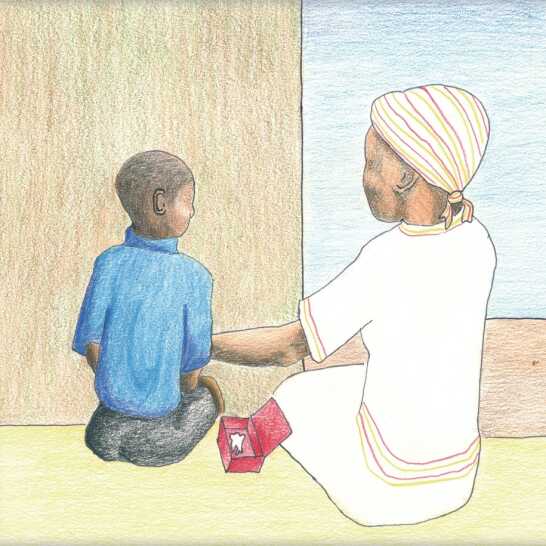

Eshi va fika keumbo, ina yaHilifa ta ningile ina otee. Meme Ndapanda ta kufa okapakete kamwe ka li koshi yombete. “Hilifa aka okoye. Mokapakete mu omu na oinima oyo tai ku kwafele okudimbuluka apa wadja.”

When they got home Hilifa’s mother was very tired. Hilifa made some tea. Meme Ndapanda took a small box from under her bed. “Hilifa, this is for you. In this box are things that will help you remember where you come from.”

Okwa kufa oidimbulukifo mokapakete kooshimwe-nooshimwe. “Eli efano laxo e ku humbata. Oove oshiveli shaye. Eli efano loye wa fanekwa eshi kwa li twe ku twala kooxokulu nanyokokulu, nova li va hafa. Eli eyoo loye lotete e li wa kuka. Oto dimbuluka eshi wa li to kwena nonda li handi ku kumaida kutya omayoo mahapu otaa ka mena. Ei ombadi nda pewelwe kuxo eshi twa hombola oule wodula imwe.”

She took the mementos out of the box one by one. “This is a photo of your father holding you. You were his firstborn son. This photo is when I took you to see your grandparents, they were so happy. This is the first tooth you lost. Do you remember how you cried and I had to promise you that more would grow. This is the brooch your father gave me when we were married for one year.”

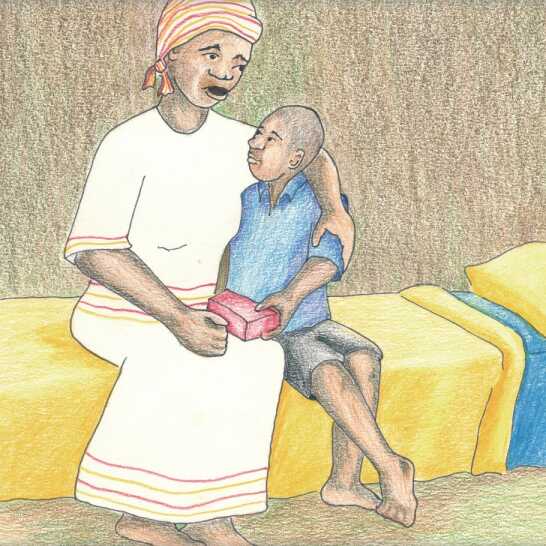

Hilifa okwa kala e kwete okapakete ndele ta tameke okukwena. Meme Ndapanda okwe mu papatela ndele tava indile, “Omwene ne ku amene ye ne ku xupife.” Okwa kala emu papatela eshi ta popi. “Hilifa mumati wange, ou shi shii kutya ame ohandi vele neenghono, nohandi ka kala pamwe naxo moule wokafimbo kaxupi. Inandi hala u nyike oluhodi. Dimbuluka kutya ondi ku hole naxo oku ku hole.”

Hilifa held the box and began to cry. His mother held him close by her side and said a prayer, “May the Lord protect you and keep you safe.” She held him as she spoke. “Hilifa, my son. You know that I am very ill, and soon I will be with your father. I don’t want you to be sad. Remember how much I love you. Remember how much your father loved you.”

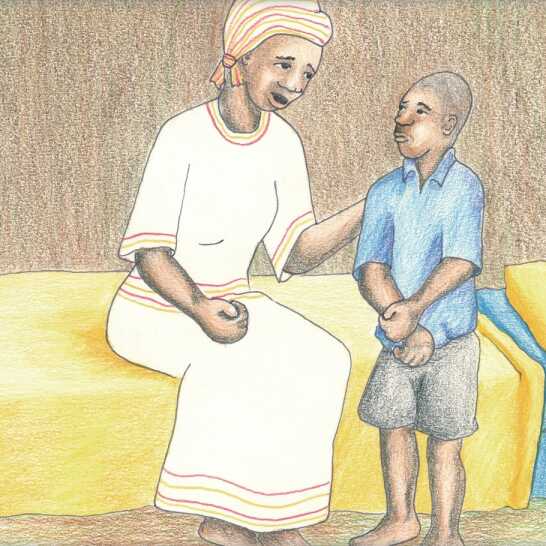

Ina ta twikile, “Xokulu Kave wokOshakati okwa kala he tu tumine oinima iwa nge e na sha. Okwa lombwela nge kutya ote ke ku fila oshisho. Onde mu lombwela nale kombinga yonghalo yoye. Oto kala ho i kofikola naKunuu omonamati waye. Kunuu oku li mOndodo onhine ngaashi ove. Otave ke ku fila oshisho.” “Ondi hole tatekulu Kave nameekulu Muzaa,” Hilifa ta ti. “Ondi hole okudanauka naKunuu. Oto kala nawa ngeenge tave ku file oshisho?” “Ahawe mumati wange, itandi kala vali nawa. Owa fila nge nawa oshisho. Onda pandula eshi ndi na omumati muwa ngaashi ove.”

His mother continued, “Uncle Kave from Oshakati sends us money when he can. He told me that he will care for you. I have talked to him about it. You’ll go to school with Kunuu, his son. Kunuu is in Grade 4 like you. They will take good care of you.” “I like Uncle Kave and Aunt Muzaa,” said Hilifa. “And I like playing with Kunuu. Would you become well if they look after you?” “No, my son. I won’t become well. You look after me very well. I am proud to have such a good son.”

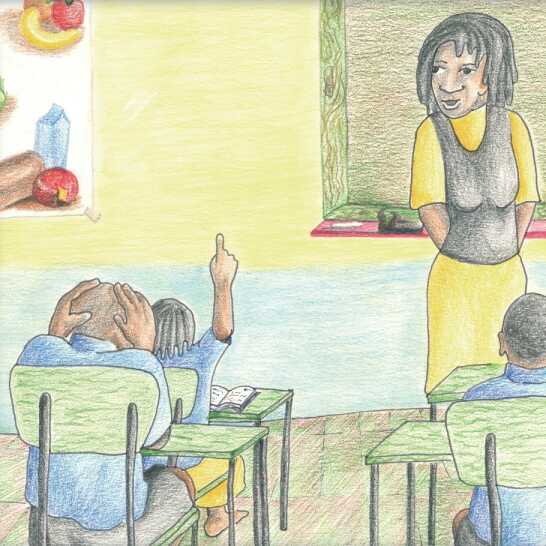

Ongula yefiku la landula kofikola mee Nelao okwe va longa kombinga yoHIV noAIDS. Ovanafikola ova li va tila. Ova uda ombuto ya tya ngaho moradio, ashike kape na ou e shi kundafana keumbo. “Ohau di peni?” Magano ta pula. “Ohau kwata ovanhu ngahelipi?” Hidipo ta pula. Mee Nelao okwa fatulula kutya oHIV edina lombuto. Ngeenge omunhu oku na ombuto mohonde, natango oha monika e na oukolele. “Ohatu ti ove na omukifi woAIDS ngeenge va tameke okuvela.”

The next morning at school Ms. Nelao taught them about HIV and AIDS. The learners looked afraid. They heard about this illness on the radio, but no-one spoke about it at home. “Where does it come from?” asked Magano. “How do we catch it?” asked Hidipo. Ms. Nelao explained that HIV is the name of a virus. When a person has the HIV virus in their blood they still look healthy. “We say they have AIDS when they become ill.”

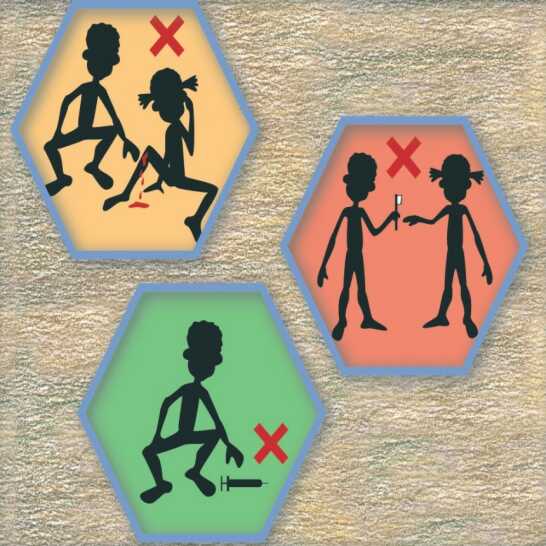

Mee Nelao okwa fatulula omikalo dimwe odo omunhu ta dulu okukwatwa kombuto. “Ngeenge omunhu oku na ombuto yoHIV ile oAIDS, ohatu dulu okukwatwa kombuto tai di mohonde yaye. Inatu longifeni oumbi ile oulikushifo vamwe naye. Ngeenge hatu li tyuuleni komatwi natu longifeni oumbi neengwiya da fulukifwa momeva. Ngeenge otwe li tu ndele hatu di ohonde, alushe natu lombwele ovakulunhu va wapaleke poipute yetu, otu na okumanga oipute nomalapi ma yela.”

Ms. Nelao explained some of the ways we can be infected with HIV. “If someone has HIV or AIDS we can catch the virus from their blood. We should never share razors or toothbrushes. If we get our ears pierced we must use sterilised blades and needles.” She explained how needles and blades should be sterilised. “If we hurt ourselves and there is blood we must ask an adult to clean the wound. We must cover the wound to protect it,” she told them.

Opo nee okwe va ulikila efano. “Edi adishe omikalo odo to dulu okulongifa opo uha kwatwe koHIV. Ito kwatwa koHIV ngeenge to longifa okandjuwo ile okalikoshelo kamwe nomunhu e na ombuto, okulipapatela, okulihupita nokuminika nomunhu ou e i na nasho kashi na oshiponga. Oshi li nawa okulongifa okakopi ile okayaxa kamwe nomunhu e na oHIV ile oAIDS. Ove ito mono ombuto komunhu ta kolola ile tatu onhisha. Navali, ito i mono okudilila moku lika keemwe, eena ile eemhombo.”

Then she showed them a chart. “These are all the ways you can’t catch HIV,” she told them. “You won’t get HIV from using the toilet, or sharing a bath. Hugging, kissing or shaking hands with someone with HIV or AIDS is also safe. It’s OK to share cups and plates with someone who has HIV or AIDS. And you can’t catch it from someone who is coughing or sneezing. Also, you can’t get it from mosquitoes or other biting insects like lice or bedbugs.”

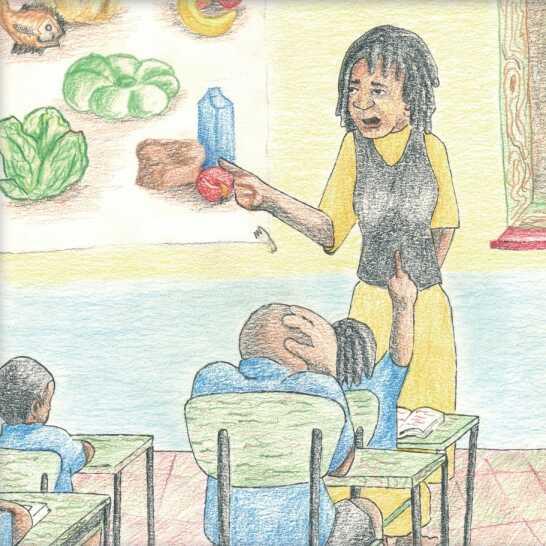

“Oto ningi ngahelipi ngeenge wa kwatwa koHIV/AIDS?” Magano ta pula. “Iyaa, ou na oku likwata nawa ove to li oikulya i na oukolele. Taleni komafano oikulya yetu,” mee Nelao ta ti. “Olye ta dimbuluka oikulya oyo iwa kuye?” natango mee Nelao ta pula.

“What do you do if you’ve got it?” asked Magano. “Well, you must take care of yourself and eat lots of healthy food. Look at our food chart,” she said. “Who can remember what food is good for you?” she asked.

Eshi Hilifa a fika keumbo okwa lombwela ina eshi ve lihonga kofikola. “Mee Nelao okwe tu lombwela kombinga yoHIV/AIDS, nonghee tu na oku fila oshisho omunhu ta vele. Magano naHidipo otava ka kwafela nge koilonga yange yomeumbo opo nee hatu ningi oshipewalonga shange,” Hilifa ta lombwele ina.

When Hilifa got home he told his mother what he had learned at school that day. “Ms. Nelao told us about HIV and AIDS and how to look after someone who’s ill. Magano and Hidipo are going to help me with my chores and we will do our homework together,” he told her.

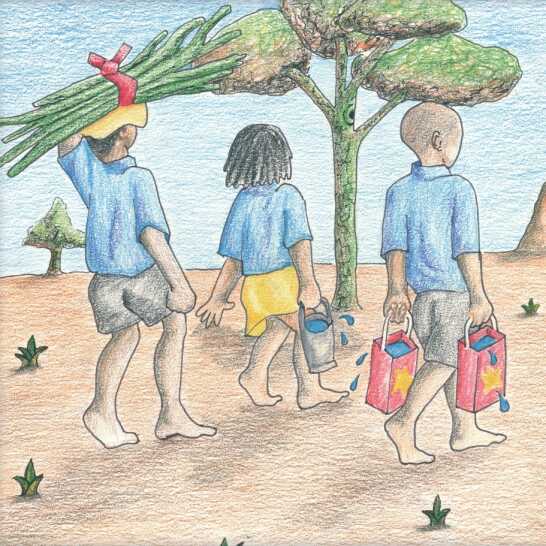

Omutenya oo Magano okwe uya a kwafe Hilifa oku ka eta omeva. Hidipo okwe va kwafela okukonga oikuni, ndele tava kala omutumba momuti womwoongo tava longo oipewalonga yavo.

That afternoon Magano came and helped Hilifa to fetch water. Hidipo helped him to gather firewood. Then they sat and did their homework in the shade of the marula tree.

Mee Nelao okwa lombwela vali ovashiinda shooHilifa kutya oye ta tonatele ina onghee ova udaneka ve mu kwafe. Oufiku keshe umwe womovashiinda shavo ohe uya noikulya ipyu opo va lye. Hilifa keshe efimbo ohe va pe oikwambidi ya dja moshikunino.

Ms. Nelao had also told Hilifa’s neighbours that he was looking after his mother. They had promised to help him. Every night a different neighbour came with hot food for them to eat. Hilifa always gave them some vegetables from the garden.

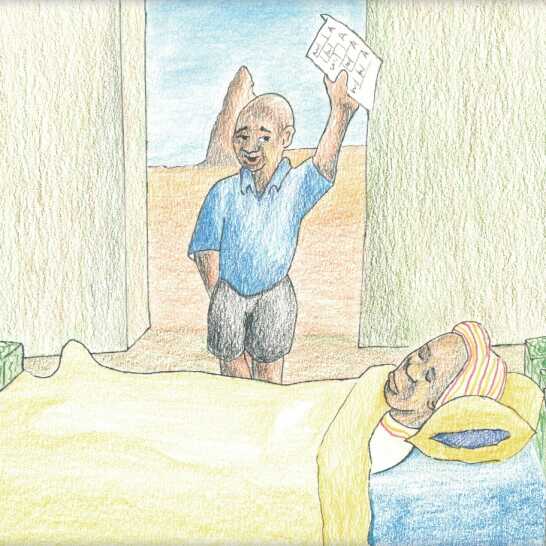

Mefiku laxuuninwa loshikako shofikola Hilifa okwa li a hafa. Okwa lotokela keumbo a ka ulikile ina odjapo yaye. Okwa lotokela mohofa yavo ta ifana, “Meme, meme, tala kondjapo yange eshi nda mona mo ‘A’, ‘A’, noo ‘A’ vahapu.” Hilifa okwa hanga ina a nangala kombete. “Meme,” ta ifana. “Meme, penduka!” Ina penduka.

On the last day of the school term Hilifa was very happy. He ran home to show his mother his report card. He ran into the yard calling, “Mum. Mum. Look at my report card. I have got ‘A’, ‘A’, and more ‘A’s’.” Hilifa found his mother lying in bed. “Mum!” he called. “Mum! Wake up!” She didn’t wake up.

Hilifa okwa tondokela kovashiinda ta ingida. “Meme yange, Meme ita penduka,” Hilifa ta kwena. Ovashiinda ova ya keumbo looHilifa nova hanga meeNdapanda a nangala kombete yaye. “Okwa fya, Hilifa,” ovashiinda tava ti noluhodi.

Hilifa ran to the neighbours. “My Mum. My Mum. She won’t wake up,” he cried. The neighbours went home with Hilifa and found Meme Ndapanda in her bed. “She is dead, Hilifa,” they said sadly.

Meendelelo onghundana oya tandavela nokutya meeNdapanda okwa fya. Eumbo okwa li liyadi ovakwapata, ovashiinda nookahewa. Ova indilila meme waHilifa, vo tava imbi omaimbilo. Ova li tava popi oinima aishe iwa ve shii kombinga yaye.

Very quickly the news spread that Meme Ndapanda was dead. The house was full of family, neighbours and friends. They prayed for Hilifa’s mother and sang hymns. They talked about all the good things they knew about her.

Inakulu Muzaa okwa telekela ovaenda aveshe. Xekulu Kave okwe mu lombwela kutya otava ka ya naye kOshakati konima yepako. Xekulu (ou a dala ina) okwe mu hokololela omahokololo kombinga yaina eshi a li okaana kokadona.

Aunt Muzaa cooked for all the visitors. Uncle Kave told Hilifa that they would take him back to Oshakati after the funeral. His Grandfather told him stories about his mother when she was a little girl.

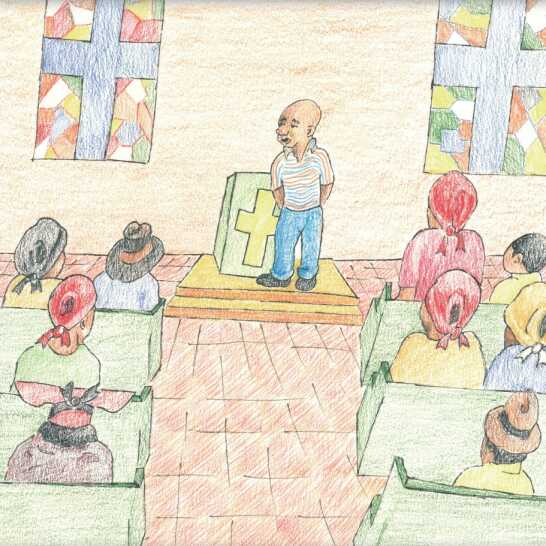

Pepako Hilifa okwa ya komesho yongeleka ndele ta lombwele keshe umwe kombinga yameme waye. “Meme okwa li e hole nge nokwa li ha file nge oshisho nawa. Okwa lombwela nge opo ndi lihonge nda mana mo ndi ka mone oilonga iwa. Okwa hala ndi kale nda hafa. Ohandi lihongo nda mana mo opo a kale e uditile nge etumba.”

At the funeral Hilifa went to the front of the church and told everyone about his mother. “My mother loved me and looked after me very well. She told me to study hard so that I could get a good job. She wanted me to be happy. I will study hard and work hard so that she can be proud of me.”

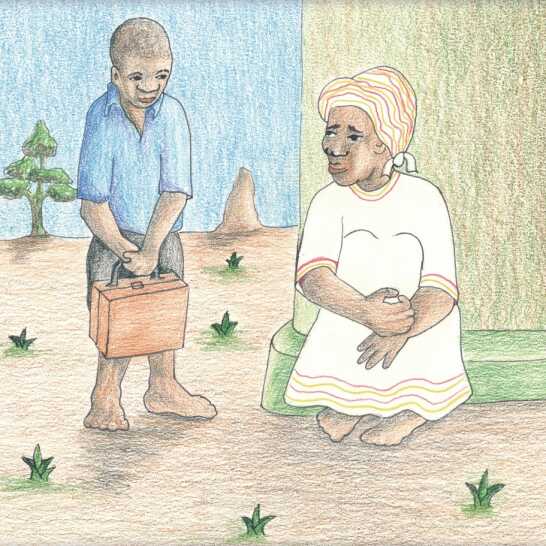

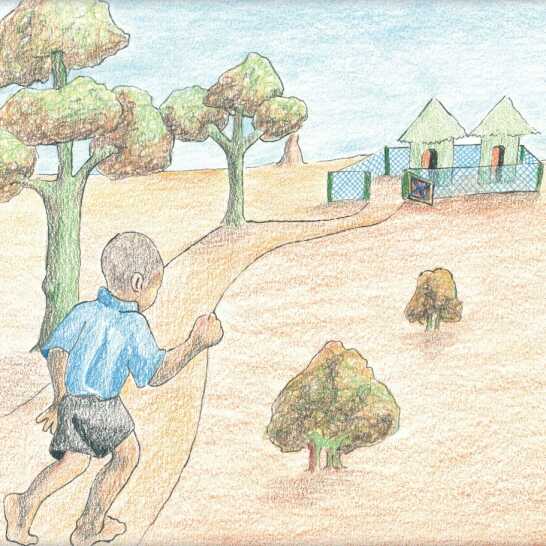

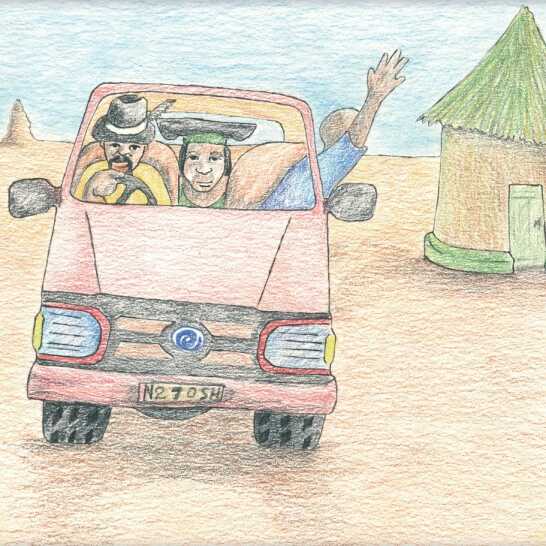

Konima yepako, Xekulu Kave na inakulu Muzaa ove mu kwafa okupakela oinima ei ta i nayo kOshakati. “Kunuu ote ke shi hafela unene okukala e na kaume mupe,” tave mu lombwele. “Ohatu ke ku fila oshisho ngaashi hatu file oshisho okamonamati ketu.” Hilifa okwa lekela eumbo ndele ta i navo noTaxi.

After the funeral Uncle Kave and Aunt Muzaa helped Hilifa to pack his things to take to Oshakati. “Kunuu is looking forward to having a new friend,” they told him. “We will care for you like our own son.” Hilifa said goodbye to the house and got into the taxi with them.

Written by: Kandume Ruusa, Sennobia-Charon Katjiuongua, Eliaser Nghitewa

Illustrated by: Jamanovandu Urike

Language: Oshikwanyama

Level: Level 5

Source: Orphans need love too from African Storybook

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.