Zazi ni zazi kakusasana Hilifa u zuhanga kapili kulukisa mukushuko wa boma he. Ba kulile hahulu mazazinyana a felile mi Hilifa na ituta kubabalela boma he ni yena muñi. Kanako ye ne ba kula hahulu boma he kuli mane ne ba sa koni kuzuha na tumbulanga mulilo kubilisa mezi kueza tii. Na isanga tii kuboma he ni kuapeha palica ya mukushuko. Fokuñwi boma he ne ba palelwa kuca bakeñisa kufokola ni kutokwa maata. Hilifa na sa ikutwi hande bakeñisa boma he. Bondata he ne ba timezi lilimo zepeli ze felile, mi cwale ni bona boma he ba kula hahulu. Ki ba basisani hahulu bakeñisa kuota, inge mo ne ba inezi bondata he.

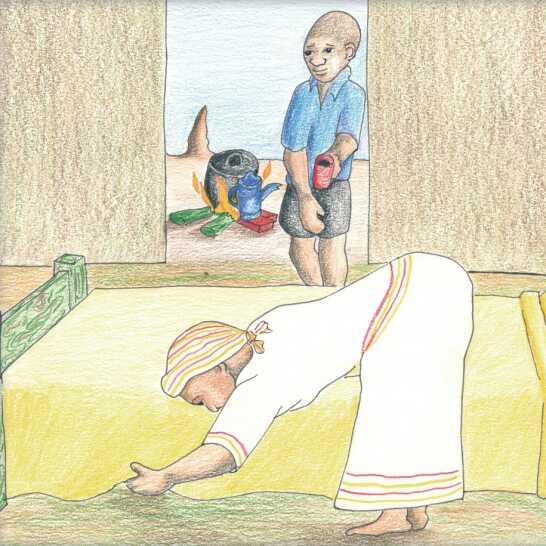

Every morning Hilifa woke up early to prepare breakfast for his mother. She had been sick a lot recently and Hilifa was learning how to look after his mother and himself. When his mother was too ill to get up he would make a fire to boil water to make tea. He would take tea to his mother and prepare porridge for breakfast. Sometimes his mother was too weak to eat it. Hilifa worried about his mother. His father had died two years ago, and now his mother was ill too. She was very thin, just like his father had been.

Zazi le liñwi kakusasana a buza boma he, “Ima, mu katazwa ki ñi? Mu ta ikutwa lili hande? Ha mu sa apeha mazazi a. Hamu koni kusebeza mwamasimu kapa kukenisa mwalapa. Hamusa ni lukisezanga lico za kuyo ca musihali, kapa kutapisa yunifomu ya ka…” “Hilifa, mwana ka wa mushimani, u na ni lilimo ze ketalizoho ka zene feela kono u kona kunibabalela hande.” A talimela mushimani ya sa fokolo a nze a komokile kuli u ta mu bulelela lika mañi. Kana ki kuli u ta utwisisa? “Ni kula hahulu. Na sepa u se u utwile kaza butuku bobubizwa AIDS. Ni na ni butuku bo,” a mu bulelela. Hilifa a kuza mizuzunyana. “Kana ki kuli taba yeo i talusa kuli ni mina mu ta timela inge bondate?” “Ha kuna kalafo ya AIDS.”

One morning he asked his mother, “What is wrong Mum? When will you be better? You don’t cook anymore. You can’t work in the field or clean the house. You don’t prepare my lunchbox, or wash my uniform…” “Hilifa my son, you are only nine years old and you take good care of me.” She looked at the young boy, wondering what she should tell him. Would he understand? “I am very ill. You have heard on the radio about the disease called AIDS. I have that disease,” she told him. Hilifa was quiet for a few minutes. “Does that mean you will die like Daddy?” “There is no cure for AIDS.”

Hilifa a liba kwasikolo a li mwamihupulo. Na si ka kena mwalingambolo ni lipapali za balikani ba hae ha ne ba nze bazamaya cwalo. “Se sifosahezi ki sikamañi?” ba mu buza. Kono Hilifa na si ka alaba, manzwi a boma he nanza bulela mwalizebe za hae. “Ha kuna kalafo. Ha kuna kalafo.” U ta ipabalela kanzila ye cwañi haiba boma he ba timela, a bilaela. U ta pila ni kuina kakai? U ta fumana kakai masheleñi a kuleka lico?

Hilifa walked to school thoughtfully. He couldn’t join in the chatter and games of his friends as they walked along. “What’s wrong?” they asked him. But Hilifa couldn’t answer, his mother’s words were ringing in his ears, “No cure. No cure.” How could he look after himself if his mother died, he worried. Where would he live? Where would he get money for food?

Hilifa a ina fatafule ya hae. A hatisa kamunwana wa hae fahalimu a lisupo ni mifanunuti ye fakota ye sesupezi fa inzi, “Ha kuna kalafo. Ha kuna kalafo.” “Hilifa? Hilifa, mane u inzi ni luna?” Hilifa a inuka. Mufumahali Nelao na mu yemelezi. “Yema Hilifa! Puzo ya ka ne li ifi?” Hilifa a talimela fafasi famautu a hae. “Ha u na kufumana kalabo fafasi fo talimezi!” a bulela. Magano, bulelela Hilifa kalabo.” Hilifa na ikutwile maswe maswabi, Mufumahali Nelao a li kuba asa mu tabelezi cwalo mwamazazi a felile.

Hilifa sat at his desk. He traced the worn wood markings with his finger, “No cure. No cure.” “Hilifa? Hilifa, are you with us?” Hilifa looked up. Ms. Nelao was standing over him. “Stand up Hilifa! What was my question?” Hilifa looked down at his feet. “You won’t find the answer down there!” she retorted. “Magano, tell Hilifa the answer.” Hilifa felt so ashamed, Ms. Nelao had never shouted at him before.

Hilifa a nyanda ona cwalo mwahal’a nako ya kakusasana. Kanako ya kuikatulusa a ina feela mwakilasi. “Ni utwa butuku mwamba,” a puma balikani ba hae. Ne si buhata luli, na ikutwa kukula, mi mihupulo ya hae ne i zezela mwatoho ya hae inge muka ye nyemile. Mufumahali Nelao a mu lisa a nze a kuzize. A mu buza kuli ki sika mañi se sifosahalile. “Ha kuna,” a alaba. Lizebe za Mufumahali Nelao a utwa mukatalo ni lipilaelo mwalinzwi la hae. Meeto a hae na boni sabo ya na lika katata kupata.

Hilifa struggled through the morning. At break time he sat in the classroom. “I have a stomach ache,” he lied to his friends. It wasn’t a big lie, he did feel sick, and his worried thoughts buzzed inside his head like angry bees. Ms. Nelao watched him quietly. She asked him what was wrong. “Nothing,” he replied. Her ears heard the tiredness and worry in his voice. Her eyes saw the fear he was trying so hard to hide.

Hilifa ha na lika kusebeza lipalo za hae, linombolo ne li kopakopani ni kutulaka mwatoho ya hae. Na sa koni kuliyemisa nako ye telele kuli a li bale. A palelwa ni kusiya. Mwasibaka sa zona a hupula boma he. Minwana ya hae ya kala kuswanisa mihupulo ya hae. A swanisa boma he mwabulobalo bwa bona. A iswanisa yena muñi a nze a yemi kwatuko a libita la boma he. “Mamonita ba lipalo, mu nge libuka za lipalo kamukana,” ku bulela Mufumahali Nelao. Kapili Hilifa a bona za swanisize mwabuka ya hae mi a lika kupazula likepe, kono ne se ku si na sibaka. Monita a isa buka ya hae kuMufumahali Nelao.

When Hilifa tried to do his maths the numbers jumped around in his head. He couldn’t keep them still long enough to count them. He soon gave up. He thought of his mother instead. His fingers began to draw his thoughts. He drew his mother in her bed. He drew himself standing beside his mother’s grave. “Maths monitors, collect all the books please,” called Ms. Nelao. Hilifa suddenly saw the drawings in his book and tried to tear out the page, but it was too late. The monitor took his book to Ms. Nelao.

Mufumahali Nelao a talima za na swanisize Hilifa. Kanako yene ba ya banana kwahae a biza, “Taha kwanu Hilifa. Ni bata kubulela kuwena.” “Ki sika mañi se sifosahezi?” a mu buza kakuiketa. “Boma ba kula. Ba ni bulelezi kuli bana ni AIDS. Kana ki kuli ba ta shwa?” “Ha ni zibi Hilifa, kono ba kula luli haiba ba na ni AIDS. Ha kuna kalafo.” Manzwi ao hape, “Ha kuna kalafo. Ha kuna kalafo.” Hilifa a kala kulila. “Zamaya kwahae, Hilifa,” a bulela. “Ni ka taha ni to lekula bomaho.”

Ms. Nelao looked at Hilifa’s drawings. When the children were leaving to go home she called, “Come here Hilifa. I want to talk to you.” “What’s wrong?” she asked him gently. “My mother is ill. She told me she has AIDS. Will she die?” “I don’t know, Hilifa, but she is very ill if she has AIDS. There is no cure.” Those words again, “No cure. No cure.” Hilifa began to cry. “Go home, Hilifa,” she said. “I will come and visit your mother.”

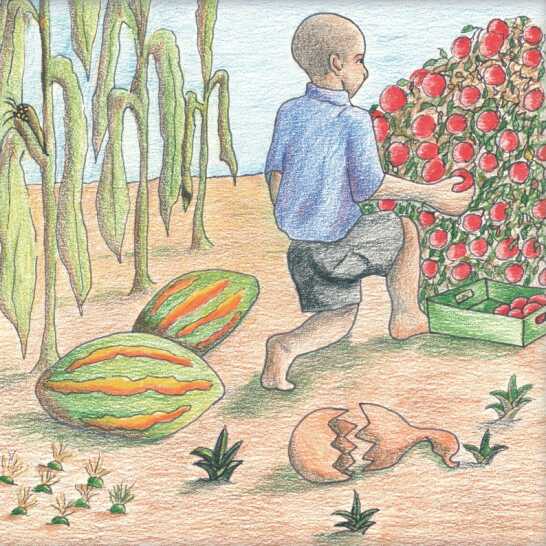

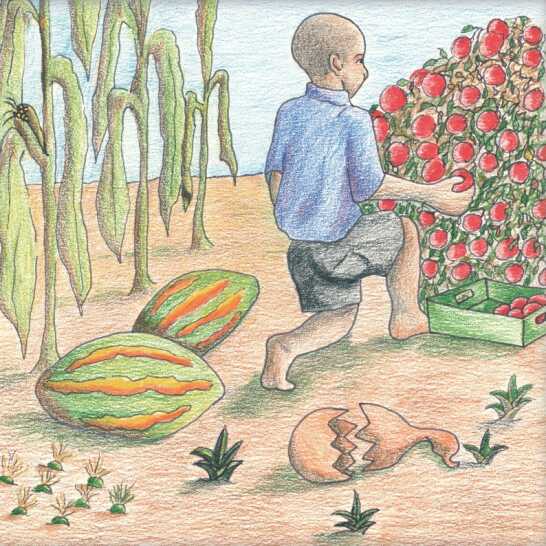

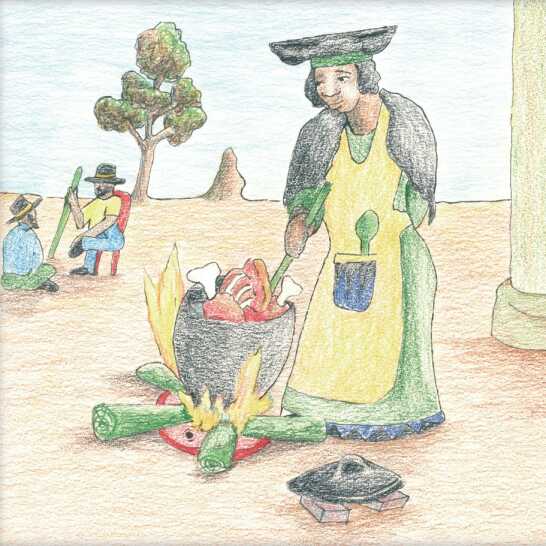

Hilifa a liba kwahae mi ayo fumana bomahe ba nze ba sweli kulukisa za lico za musihali. “Ni ku apehezi kacenu, Hilifa, kono onafa ni katezi maswe. U tokomele simu ya muloho mi uise matamakisi a likani kwasintolo. Ba ta yo lu lekiseza ona.” Kasamulaho a lico za musihali Hilifa a liba kwamumbeta wa miloho. A talima mibala ye kanya ya miloho, bufubelu bobukanya bwa matamakisi ni mbilimbili, manawa a matelele a matala ni sipinaci sa butala bobunsu, matali a matala a ngulu ni mbonyi ye telele ya gauda. A selaela mumbeta ni kunga saka ye tezi matamakisi a mafubelu a buzwize kuisa kwasintolo. “Ki sika mañi se sita ezahala kwasimu ya bona ya miloho haiba bomahe ba timela?” a ikupula.

Hilifa went home and found his mother preparing lunch. “I’ve cooked for you today, Hilifa, but now I am very tired. Look after the vegetable garden and take some tomatoes to the shop. They will sell them for us.” After lunch Hilifa went to the vegetable plot. He looked at the bright colours of the vegetables, bright red tomatoes and chillies, long green beans and dark green spinach, the green leaves of the sweet potato and tall golden maize. He watered the garden and picked a bag full of ripe red tomatoes to take to the shop. “What would happen to their garden if his mother died?” he wondered.

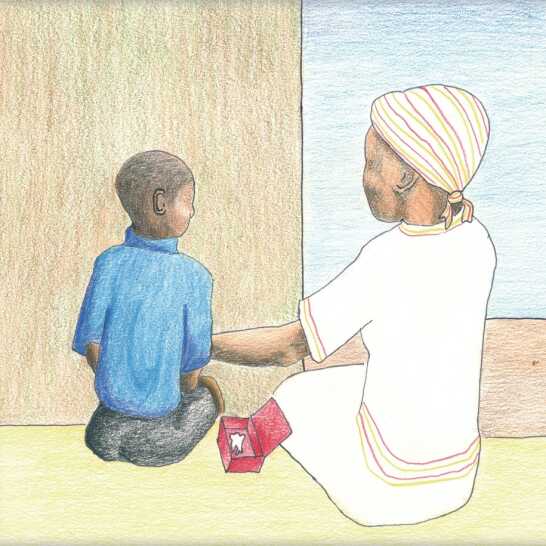

Mufumahali Nelao a to fita nakonyana feela kuzwa fa fundukela Hilifa. A nga nako ye telele a nze a bulela kubom’a he Hilifa. A ba buza, “Musali muhulu Ndapanda, mane mu sweli kunwa milyani ya AIDS?” “Kasamulaho a muunaka sa timezi ne ni ikutwile hahulu maswabi kuya kuñaka,” a bulelela Mufumahali Nelao. “Neninze ni hupula kuli nenisika yambula. Ha ni kala kukula ni kuliba kuñaka, a yo ni bulelela kuli ni lyehile. Mulyani hausa kona kunitusa.” Mufumahali Nelao a bulelela Musali muhulu Ndapanda sa swanela kueza kutusa Hilifa.

Ms. Nelao arrived soon after Hilifa left. She spent a long time talking to his mother. She asked Hilifa’s mother, “Meme Ndapanda, are you taking the medicine for AIDS?” “After my husband died I was too ashamed to go to the doctor,” she told Ms. Nelao. “I kept hoping I wasn’t infected. When I became ill and went to the doctor she told me it was too late. The medicine would not help me.” Ms. Nelao told Meme Ndapanda what to do to help Hilifa.

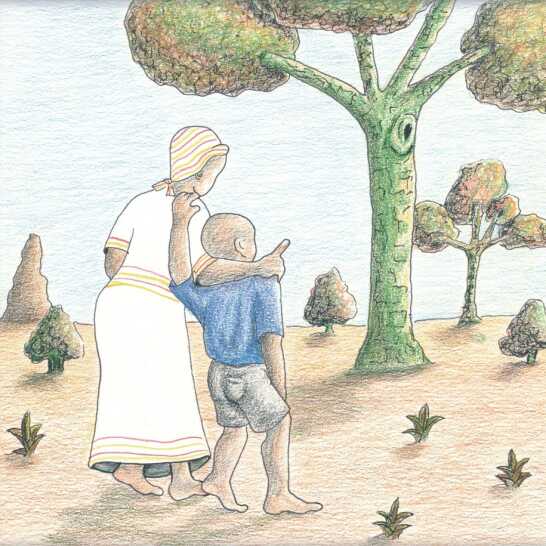

Hilifa ha tile kwahae boma he ba mu kupa, “Hilifa mwana ke. Ni bata kuzamazamaya ni wena hanyinyani. Ha ku ni tuse?” Hilifa a nga mwambo wa boma he mi ba tiyela kuyena. Bazamaya kuliba ko kumela likota za muhoto ze telele. Ba mu buza, “Kana u sa hupula hanemu bapala mbola ni mwana banyani ba bondata ho Kunuu? No kile wa lahela mbola mwakota mi ya kakatela mwamiutwa. Bondataho ba fanaunwa ki miutwa kulika kukupahululela yona.”

When Hilifa came home his mother asked him, “Hilifa, my son, I want to take a walk with you. Will you help me?” Hilifa took his mother’s arm and she leaned on him. They walked to where the tall thorn trees grew. She asked him, “Do you remember playing football here with your cousin Kunuu? You kicked the ball into the tree and it got stuck on the thorns. Your father got scratched getting it down for you.”

“Bona, sibumbu sa muzuzunyani ki sani. Zamaya uyo sela hanyinyani u ise kwahae.” Hilifa hana sweli kusela namulomolomo ya munati, bomahe bali, “Kana usa hupula inge u sa li mwanana ha no kile wa mizeleza namulomolomo ni litoze za teñi. Ne u si ka ya kwalibala sunda mutumbi!” “Eeni, mba yaka ne i utwa hahulu butuku,” kwa hupula Hilifa anze a seha.

“Look, there’s an omandjembere bush. Go and pick some to take home.” When Hilifa was picking the sweet berries, she said, “Do you remember when you were small you ate the berries and the seed inside. You didn’t go to the toilet for a week!” “Yes, my stomach was sooo sore,” remembered Hilifa, laughing.

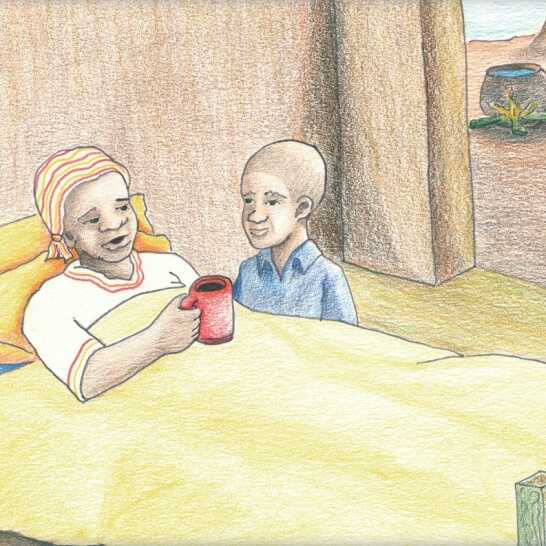

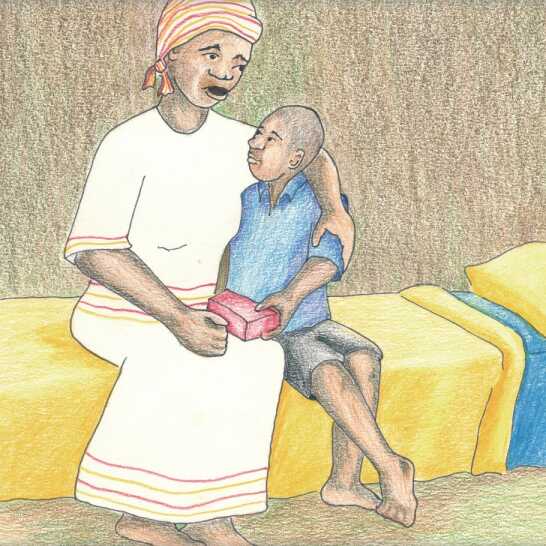

Haba fitile kwahae, boma he Hilifa ne ba katezi hahulu. Hilifa a eza tii. Musali muhulu Ndapanda a nga kapokisi mwatas’a mumbeta wa hae. “Hilifa, nto ye ki ya hao. Mwapokisi ye kuna ni lika ze ta ku hupulisa ko zwa.”

When they got home Hilifa’s mother was very tired. Hilifa made some tea. Meme Ndapanda took a small box from under her bed. “Hilifa, this is for you. In this box are things that will help you remember where you come from.”

A zwisa likupuliso mwapokisi i liñwi ka i liñwi. “Se ki siswaniso sa bondat’a ho inge ba ku sweli. Ne li wena mweli wa bona wa mushimani. Se ki siswaniso ha ne ni ku isize kubokukwa hao, ne ba tabile hahulu. Le kona liino la hao la pili leneli kulehile. U sa hupula mono kile wa lilela mi neninani kukusepisa kuli a mañata a ta mela. Ye ki pini ya kabisa yene bakile banifa bondat’aho inge lunani silimo si li siñwi kuzwa folu nyalanela.”

She took the mementos out of the box one by one. “This is a photo of your father holding you. You were his firstborn son. This photo is when I took you to see your grandparents, they were so happy. This is the first tooth you lost. Do you remember how you cried and I had to promise you that more would grow. This is the brooch your father gave me when we were married for one year.”

Ha na nze a sweli pokisi, Hilifa a kala kulila. Bom’ehe ba swalani ni kumuhohela kwatuko ni bona ni kubulela tapelo, “Muña Bupilo a ku sileleze ni kukubuluka kakozo.” Neba nze ba mu swalelezi ha ba nze ba bulela. “Hilifa mwan’a ka wa mushimani. Wa ziba hande kuli ni kula hahulu, mi ha kuna kufita mazazi ni ta be ni izo ikopanya ni ndat’a ho. Ha ni lati kuli u ikutwe bumaswe. U hupule butuna bwa lilato la ka kuwena. U hupule lilato leo neba kulata kalona bondat’a ho.”

Hilifa held the box and began to cry. His mother held him close by her side and said a prayer, “May the Lord protect you and keep you safe.” She held him as she spoke. “Hilifa, my son. You know that I am very ill, and soon I will be with your father. I don’t want you to be sad. Remember how much I love you. Remember how much your father loved you.”

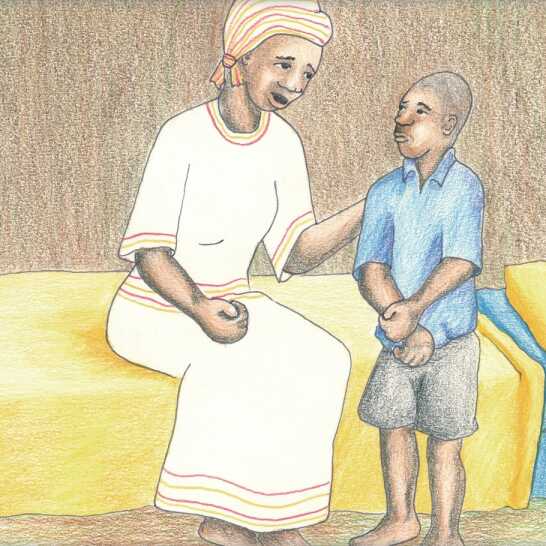

Bom’a he ba zwelapili. “Malum’a ho ya li kwaOshakati u lu lumelanga masheleñi ha ku konahala kueza cwalo. U ni bulelezi kuli u ta ku babalela. Ni ambozi ni yena kaza taba ye. U ta yanga kwasikolo ni Kunuu mwan’a hae. Kunuu u inzi mwaSitopa sa bune inge wena. Ba ta ku babalela hande.” “Ni tabela malume Kave ni ndatenengo Muzaa,” ku bulela Hilifa. “Mi ni tabela maswe kubapala ni Kunuu. Kana ki kuli mu ta fola haiba kuli ba mi babalela?” “Baatili mwan’a ka. Ha ni na kufola. U sweli kunibabalela hande. Na ikumusa kuba ni mwana yo munde sina wena.”

His mother continued, “Uncle Kave from Oshakati sends us money when he can. He told me that he will care for you. I have talked to him about it. You’ll go to school with Kunuu, his son. Kunuu is in Grade 4 like you. They will take good care of you.” “I like Uncle Kave and Aunt Muzaa,” said Hilifa. “And I like playing with Kunuu. Would you become well if they look after you?” “No, my son. I won’t become well. You look after me very well. I am proud to have such a good son.”

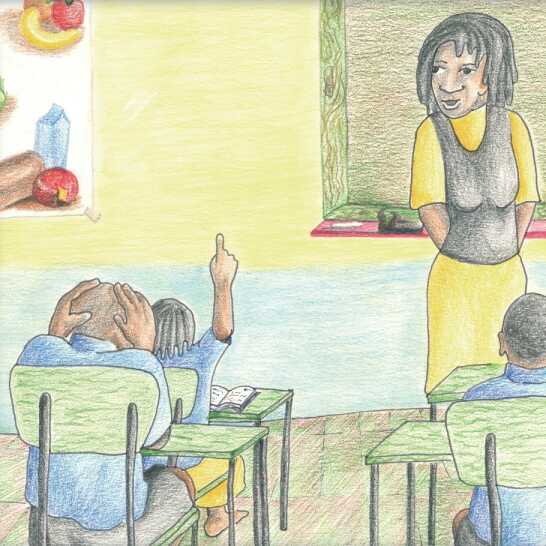

Lizazi le litatama kwasikolo Mufumahali Nelao a ba luta kaza HIV ni AIDS. Banana ne ba bonahala kusaba maswe. Ba utwile kaza butuku bofawayilesi, kono ha kuna ya na bulela kaza teñi kwahae. “Bu zwa ka kai?” ku buza Magano. “Lu bu fumana cwañi?” ku buza Hidipo. Mufumahali Nelao a talusa kuli HIV ki libizo la kakokwani. Mutu niha na ni kakokwani mwamali u sa bonahala kuba ya na ni makete asa kuli. “Lu bulela kuli ba na ni AIDS ha ba kala kukula.”

The next morning at school Ms. Nelao taught them about HIV and AIDS. The learners looked afraid. They heard about this illness on the radio, but no-one spoke about it at home. “Where does it come from?” asked Magano. “How do we catch it?” asked Hidipo. Ms. Nelao explained that HIV is the name of a virus. When a person has the HIV virus in their blood they still look healthy. “We say they have AIDS when they become ill.”

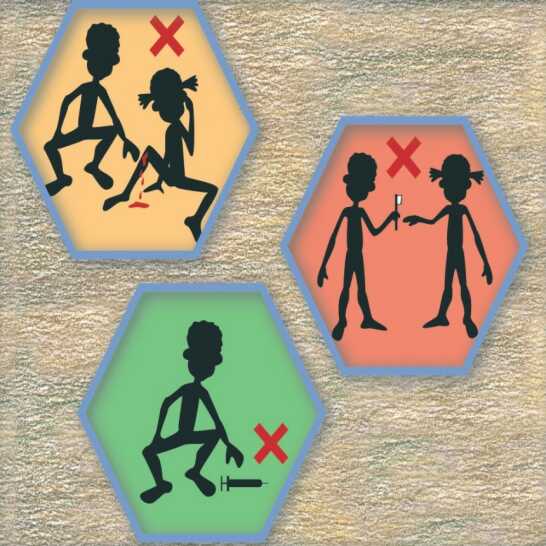

Mufumahali Nelao a talusa kalinzila zeñwi mo lu kona kuyambulela HIV. “Haiba mutu u na ni HIV kapa AIDS lu kona kuyambula kakokwani mwamali a bona. Lu si ke lwa lika ni kamuta kukopanela kabemba kapa sikwakuliso sa meeno. Haiba lu utwa kuli lizebe za luna li utwa butuku lu tameha kusebelisa tubemba ni lindonga ze bilisizwe.” “Haiba lu ikolofaza mi kuna ni mali lu tameha kukupa mutu yo muhulu kukenisa sitombo. Lu tameha kuapesa sitombo i li kusisileleza,” a ba bulelela.

Ms. Nelao explained some of the ways we can be infected with HIV. “If someone has HIV or AIDS we can catch the virus from their blood. We should never share razors or toothbrushes. If we get our ears pierced we must use sterilised blades and needles.” She explained how needles and blades should be sterilised. “If we hurt ourselves and there is blood we must ask an adult to clean the wound. We must cover the wound to protect it,” she told them.

Kutuhafo a ba supeza cati. “A tatama kona manzila feela ao mu sa yambuli HIV kaona,” a ba bulelela. “Ha u na kufumana HIV kakusebelisa simbuzi, kapa kukopanela sitapelo. Kuswalana ni mutu mwambando, kapa kutubetana kapa mane kuswalana ni mutu yanani HIV kapa AIDS mwamazoho ha kuna kozi. Ha kuna kozi kukopanela likomoki kapa lipuleti ni mutu ya kula HIV kapa AIDS. Mi hape ha u koni kuyambula kakokwani kuzwelela kumutu ya hotola kapa kuitimuna. Kutuhafo hape ha mu koni kuyambula kakokwani kao kakulumiwa ki minañi kapa likokwani ze luma ze cwale ka linda kapa liñanya.”

Then she showed them a chart. “These are all the ways you can’t catch HIV,” she told them. “You won’t get HIV from using the toilet, or sharing a bath. Hugging, kissing or shaking hands with someone with HIV or AIDS is also safe. It’s OK to share cups and plates with someone who has HIV or AIDS. And you can’t catch it from someone who is coughing or sneezing. Also, you can’t get it from mosquitoes or other biting insects like lice or bedbugs.”

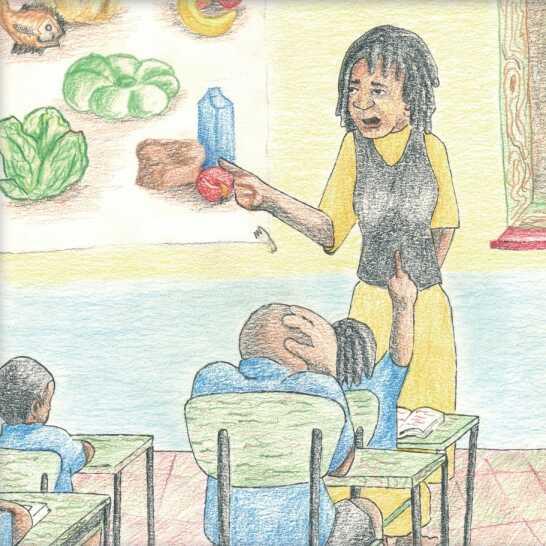

“U kona kueza cwañi haiba u fumaneha kuba ni yona?” ku buza Magano. “Ha kuna, u swanela kuipabalela ni kuca lico ze makete. Talima cati ya luna ya lico,” a bulela. “Ki mañi ya sa hupula kuli ki lico mañi zende kuwena?” a buza.

“What do you do if you’ve got it?” asked Magano. “Well, you must take care of yourself and eat lots of healthy food. Look at our food chart,” she said. “Who can remember what food is good for you?” she asked.

Hilifa ha fitile kwahae na bulelezi bom’a he kaza na izo ituta kwasikolo lizazi leo. “Mufumahali Nelao ulu bulelezi kaza HIV ni AIDS ni kamo lu swanela kubabalelela mutu ya kula. Magano ni Hidipo bata ni tusa kwamisebezinyana yaka mi luta eza musebezi ya sikolo ya kuezeza kwahae hamoho,” a bulelela m’a he.

When Hilifa got home he told his mother what he had learned at school that day. “Ms. Nelao told us about HIV and AIDS and how to look after someone who’s ill. Magano and Hidipo are going to help me with my chores and we will do our homework together,” he told her.

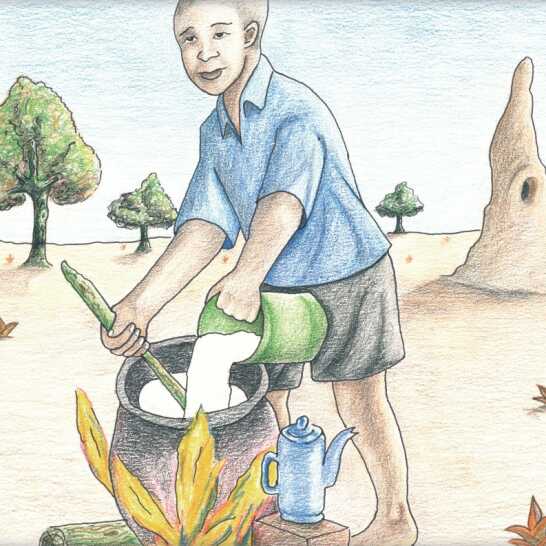

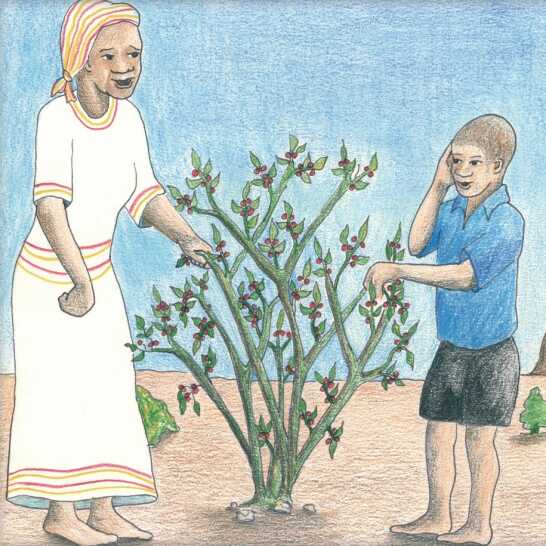

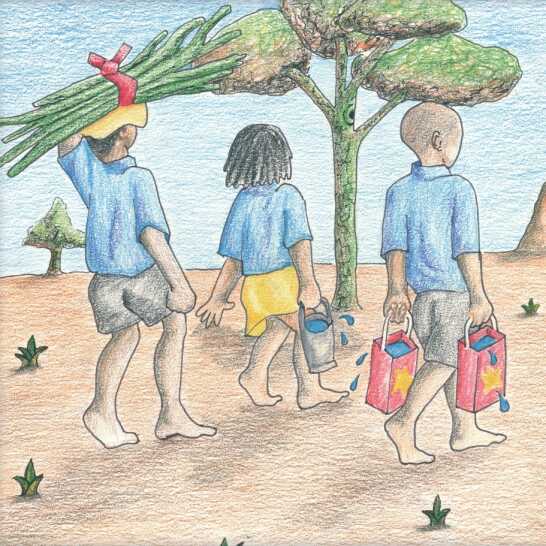

Manzibuana a lizazi leo Magano natile kuto tusa Hilifa kuyo ka mezi. Hidipo na mu tusize kuyo lwalela likota. Kutuhafoo se ba ina ni kusebeza musebezi wa bona wa sikolo wa kusebeleza kwahae mwatas’a muluti wa kota ya mulula.

That afternoon Magano came and helped Hilifa to fetch water. Hidipo helped him to gather firewood. Then they sat and did their homework in the shade of the marula tree.

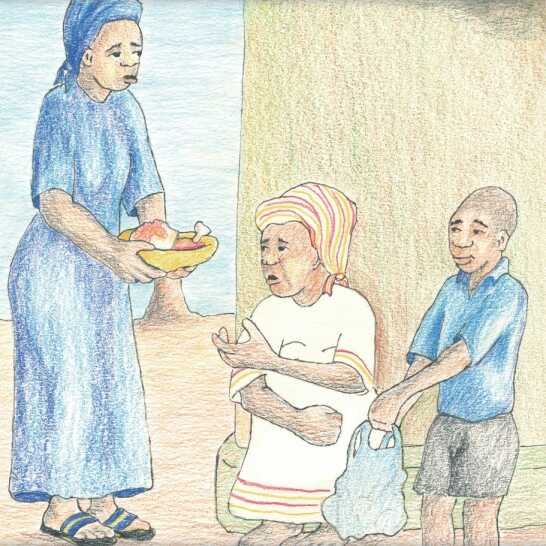

Mufumahali Nelao ni yena na kile a bulelela ba bayahile kwatuko ni lapa la habo Hilifa kuli u sweli kukulisa bom’a he. Ne ba sepisize kuli ba kana bamu tusa. Zazi ni zazi busihu, alimuñwi kuba bayahile kwatuko ni bona na tisanga lico ze sa cisa kuli ba toca. Hañata Hilifa na ba fanga kwamuloho o zwa mwasimu ya miloho.

Ms. Nelao had also told Hilifa’s neighbours that he was looking after his mother. They had promised to help him. Every night a different neighbour came with hot food for them to eat. Hilifa always gave them some vegetables from the garden.

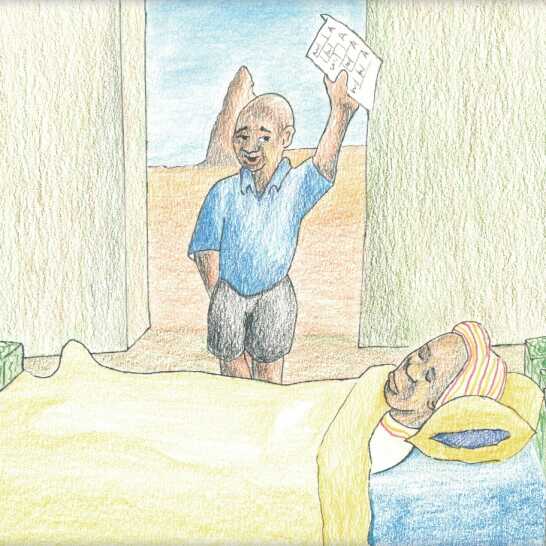

Lizazi la mafelelezo a temu Hilifa na tabile hahulu. Na matezi kwahae kuyo supeza bom’a he kakalata ka linepo za hae. A matela mwalapa a nze a biza “Ima, Ima. Amubone kalata ya linepo za ka. Ni fumani ‘A’, ‘A’, ni ma ‘A’ a mañata.” Hilifa a fumana bom’ahe inge ba lobezi famumbeta. “Ima!” a biza. “Ima! Hamu zuhe!” Ne ba si ka zuha.

On the last day of the school term Hilifa was very happy. He ran home to show his mother his report card. He ran into the yard calling, “Mum. Mum. Look at my report card. I have got ‘A’, ‘A’, and more ‘A’s’.” Hilifa found his mother lying in bed. “Mum!” he called. “Mum! Wake up!” She didn’t wake up.

Hilifa a matela ku ba bayahile kwatuko ni bona. “Boma. Boma. Ha ba koni kuzuha,” a lila. Babayahile kwatuko ni bona ba liba kwandu ni Hilifa mi ba fumana kuli Musali Muhulu Ndapanda mwabulobalo bwa hae. “Ba timezi, Hilifa,” ba bulela kamaswabi.

Hilifa ran to the neighbours. “My Mum. My Mum. She won’t wake up,” he cried. The neighbours went home with Hilifa and found Meme Ndapanda in her bed. “She is dead, Hilifa,” they said sadly.

Kapili-pili mafuko a hasana a kuli Musali Muhulu Meme Ndapanda u timezi. Ndu ya tala ba lubasi, ba bayahile kwatuko ni bona ni balikani. Ba lapelela bom’a he Hilifa ni kuopela lipina. Ba bulela kaza lika kaufela zende zeneba ziba kaza hae.

Very quickly the news spread that Meme Ndapanda was dead. The house was full of family, neighbours and friends. They prayed for Hilifa’s mother and sang hymns. They talked about all the good things they knew about her.

Ndatenengo Muzaa a apehela bapoti kamukana. Malume Kave a bulelela Hilifa kuli ba ta mu nga ni kuya ni yena kwaOshakati kasamulaho a kepelo. Bokukwa hae ba mu taluseza makande a za bom’ahe hane basali kasizana.

Aunt Muzaa cooked for all the visitors. Uncle Kave told Hilifa that they would take him back to Oshakati after the funeral. His Grandfather told him stories about his mother when she was a little girl.

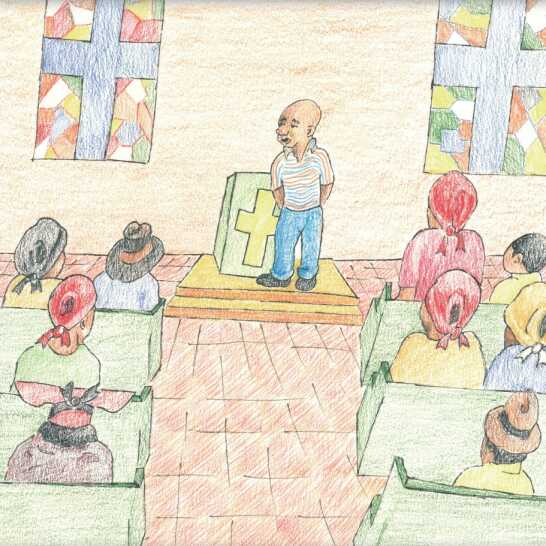

Kanako ya kepelo Hilifa nakile a liba fapaata mwakeleke ni kutaluseza batu kaufela kaza bom’a he. “Boma ne ba ni lata hakalo mi ne ba ni babalela kaswanelo. Neba kile ba ni bulelela kuli ni itute katata i li kuli ni te ni fumane musebezi wa ngana. Nika ituta katata ni kusebeza katata ili kuli ba te ba ikumuse bakeñisa ka.”

At the funeral Hilifa went to the front of the church and told everyone about his mother. “My mother loved me and looked after me very well. She told me to study hard so that I could get a good job. She wanted me to be happy. I will study hard and work hard so that she can be proud of me.”

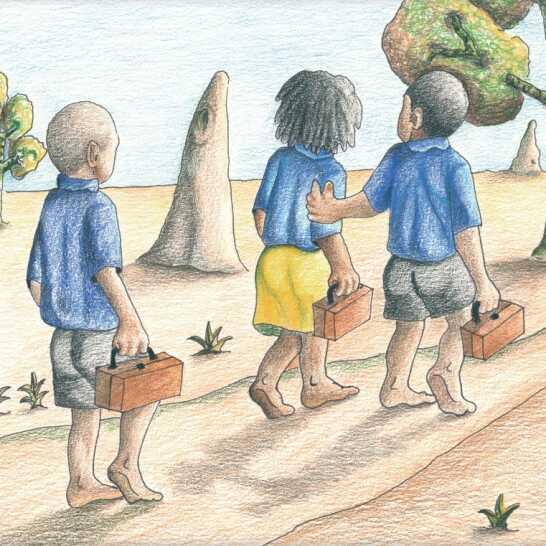

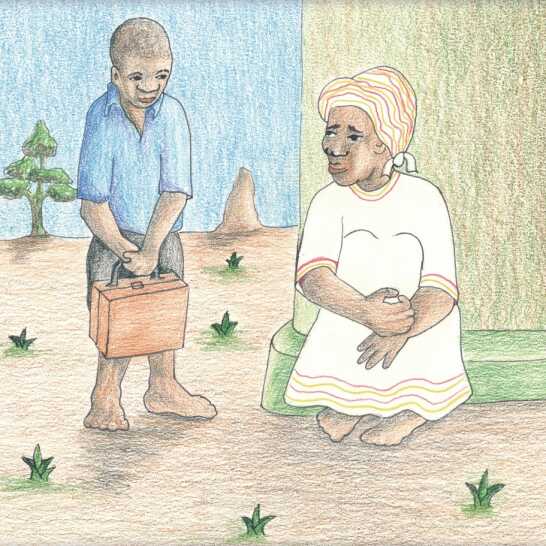

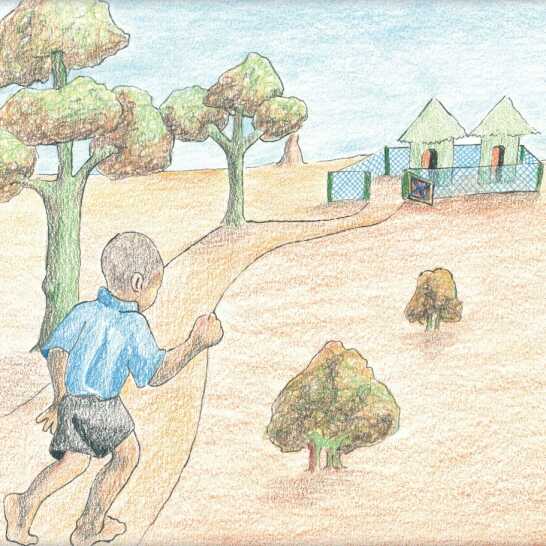

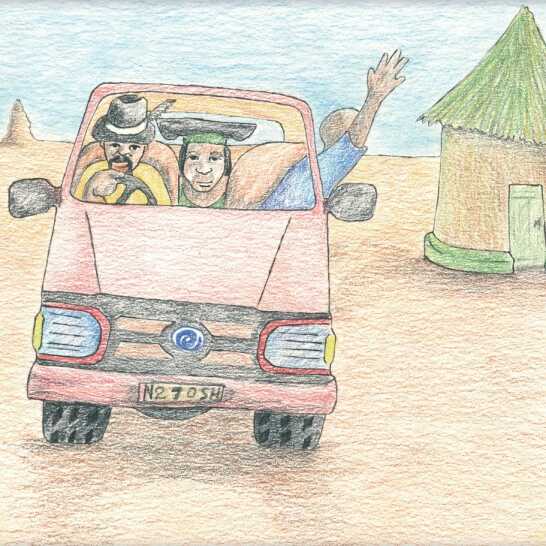

Kasamulaho a kepelo Malume Kave ni Ndatenengo Muzaa ba tusa Hilifa kuputa lika za hae ni kumunga kuya kwaOshakati. “Kunuu u libelezi kuba ni mulikani yo munca,” ba mu bulelela. “Lu ta kubabalela inge mwan’a luna wa mushimani.” Hilifa a laeza ndu ya habo ni kukwela taxi ni bona.

After the funeral Uncle Kave and Aunt Muzaa helped Hilifa to pack his things to take to Oshakati. “Kunuu is looking forward to having a new friend,” they told him. “We will care for you like our own son.” Hilifa said goodbye to the house and got into the taxi with them.

Written by: Kandume Ruusa, Sennobia-Charon Katjiuongua, Eliaser Nghitewa

Illustrated by: Jamanovandu Urike

Read by: Chrispin Musweu, Margaret Wamuwi Sililo

Language: siLozi

Level: Level 5

Source: Orphans need love too from African Storybook

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.