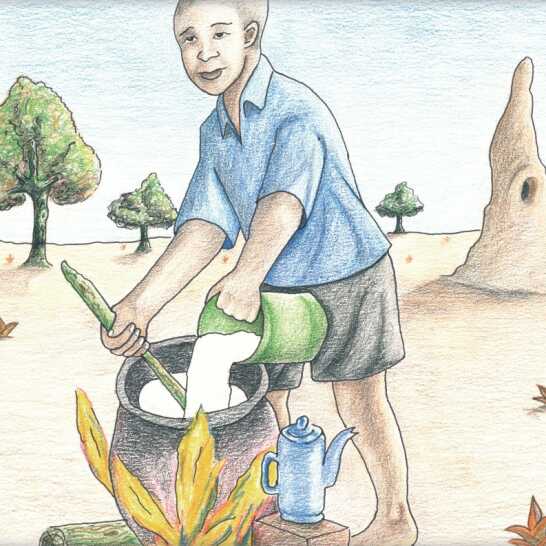

Moso le moso, Hilifa o ne a tsoga maphakela go baakanyetsa mmaagwe sefitlholo. O bobotse thata boseng jaana e bile Hilifa o ne a ithuta go itlhokomela le go tlhokomela mmaagwe. Fa mmaagwe a le bokoa thata go ka ema, o ne a gotsa molelo go bidisa metsi mme a dire tee. O ne a e mo isetsa morago a apeye bogobe jwa phakela. Ka dinako tse dingwe, mmaagwe o ne a palelwa le ke go e ja. Hilifa o ne a mo ngongoregela. Rraagwe o tlhokafetse dingwaga tse pedi tse di fetileng jaanong mmagwe le ene o a lwala. O ne a bopame thata fela jaaka rraagwe a ne a ntse.

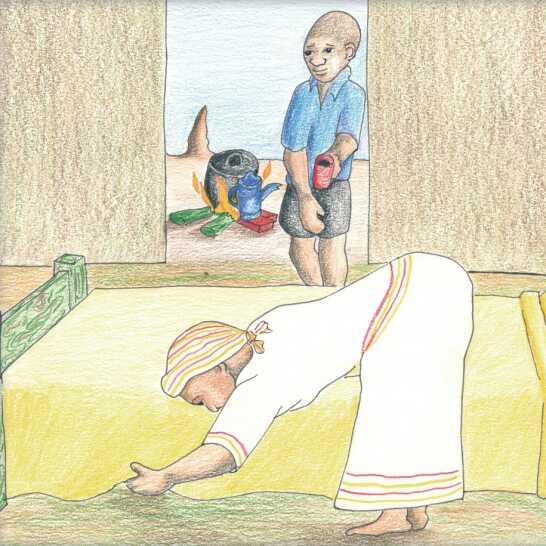

Every morning Hilifa woke up early to prepare breakfast for his mother. She had been sick a lot recently and Hilifa was learning how to look after his mother and himself. When his mother was too ill to get up he would make a fire to boil water to make tea. He would take tea to his mother and prepare porridge for breakfast. Sometimes his mother was too weak to eat it. Hilifa worried about his mother. His father had died two years ago, and now his mother was ill too. She was very thin, just like his father had been.

Mo mosong mongwe a botsa mmaagwe a re “Molato ke eng Mma? O tla tokafala leng? Ga o tlhole o apaya. Ga o kgone go dira kwa masimong le gone go phepafatsa ntlo. Ga o mpaakanyetse dijo tsa motshegare kgotsa go tlhatswa diaparo tsa me tsa sekolo…” “Hilifa morwaaka, o dingwaga fela tse robongwe e bile o ntlhokomela sentle.” A leba mosimanyana mme a ipotsa gore a mo arabe a reng. A o tlaa tlhaloganya? “Ke lwala fela thata. O utlwile mo seromamoweng ka mogare o o bidiwang AIDS. Ke na le one,” a mmolelela. Hilifa a didimala metsotso se kae. “A go raya gore o ya go tlhokafala fela jaaka rre? “Ga go na kalafi ya mogare wa AIDS.”

One morning he asked his mother, “What is wrong Mum? When will you be better? You don’t cook anymore. You can’t work in the field or clean the house. You don’t prepare my lunchbox, or wash my uniform…” “Hilifa my son, you are only nine years old and you take good care of me.” She looked at the young boy, wondering what she should tell him. Would he understand? “I am very ill. You have heard on the radio about the disease called AIDS. I have that disease,” she told him. Hilifa was quiet for a few minutes. “Does that mean you will die like Daddy?” “There is no cure for AIDS.”

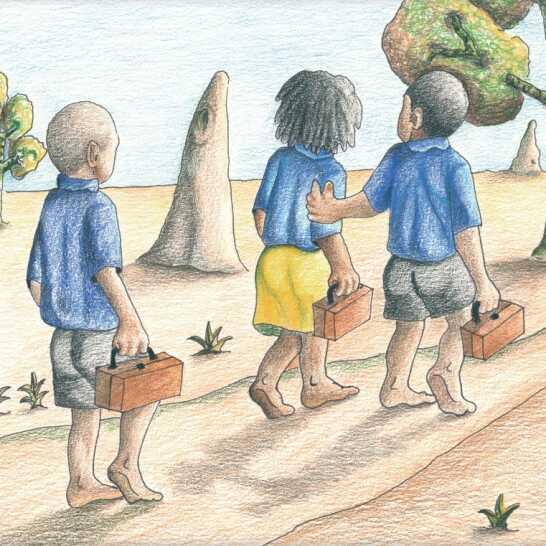

Hilifa o ile sekolong a akanya thata. O ne a sa kgone go tsenelela dikgang le metshameko ya ditsala tsa gagwe jaaka ba ntse ba tsamaya jalo. “Molato ke eng?”, ba mmotsa. O ne sa kgone go ba araba ka mafoko a ga mmaagwe a ne a duma mo ditsebeng tsa gagwe, “Ga go na kalafi. Ga go na kalafi”. O ne a ngongorega gore o ya go itlhokomela jang fa mmaagwe a ka tlhokafala. O ne a ya go nna kae? O ne a ya go bona kae madi a go reka dijo?

Hilifa walked to school thoughtfully. He couldn’t join in the chatter and games of his friends as they walked along. “What’s wrong?” they asked him. But Hilifa couldn’t answer, his mother’s words were ringing in his ears, “No cure. No cure.” How could he look after himself if his mother died, he worried. Where would he live? Where would he get money for food?

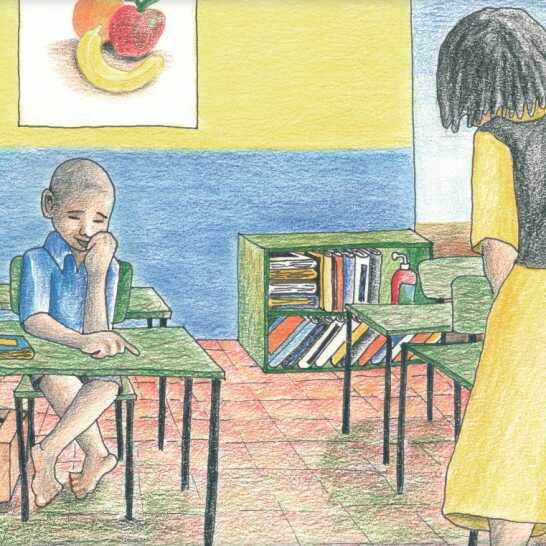

Hilifa o ne a dutse fa tafoleng ya gagwe a tsamaisa monwana wa gagwe mo matshwaong a bogologolo a a dirilweng mo tafoleng, “Ga go na kalafi. Ga go na kalafi.” “Hilifa? Hilifa, a re mmogo? A tsholetsa sefatlhogo. Mme Nelao o ne a eme fa pele ga gagwe. “Ema Hilifa! Potso ya me e ne e le eng?” Hilifa a leba kwa dinaong tsa gagwe. “Ga o kitla o bona karabo ko tlase koo!” a gatelela. “Magano, bolelela Hilifa karabo.” Hilifa o ne a tlhabiwa ke ditlhong ka gore Mme Nelao ga a ise a ke a mo goelele.

Hilifa sat at his desk. He traced the worn wood markings with his finger, “No cure. No cure.” “Hilifa? Hilifa, are you with us?” Hilifa looked up. Ms. Nelao was standing over him. “Stand up Hilifa! What was my question?” Hilifa looked down at his feet. “You won’t find the answer down there!” she retorted. “Magano, tell Hilifa the answer.” Hilifa felt so ashamed, Ms. Nelao had never shouted at him before.

Hilifa o ne a palelwa go tswa mo nakong ya maphakela. Ka nako ya dijo o ne a nna fela mo phaposing ya borutelo. “Mogodu wa me o a thunya”, a aketsa ditsala tsa gagwe. E ne e se maaka a magolo, o ne a ikutlwa a lwala. Dikakanyo tsa ngongorego mo go ene di ne di duma jaaka dinotshe tse di galefileng. Mme Nelao a mo lebile ka tidimalo. A mmotsa gore molato ke eng. “Sepe,” a araba. Ditsebe tsa gagwe di ile tsa utlwa letsapa le ngongora mo lentsweng la gagwe. Matlho a gagwe a ne a bona poifo e a neng a batla go e fitlha tota.

Hilifa struggled through the morning. At break time he sat in the classroom. “I have a stomach ache,” he lied to his friends. It wasn’t a big lie, he did feel sick, and his worried thoughts buzzed inside his head like angry bees. Ms. Nelao watched him quietly. She asked him what was wrong. “Nothing,” he replied. Her ears heard the tiredness and worry in his voice. Her eyes saw the fear he was trying so hard to hide.

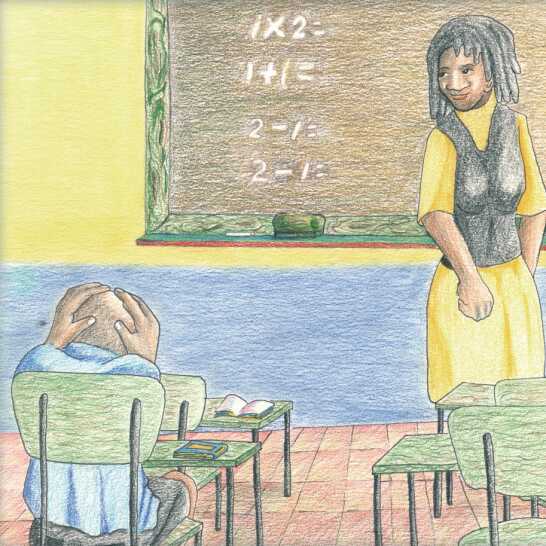

Fa Hilifa a leka go dira dipalo tsa gagwe di ne di tlolaka mo tlhogong ya gagwe. O ne a palelwa ke go di koafatsa lebaka gore a kgone go di bala. Bofelelong a itlhoboga. O ne a akanya ka ga mmaagwe jaanong. Menwana ya gagwe e ne ya simolola go tshwantshisa dikakanyo tsa gagwe. A tshwantshisa mmaagwe a rapame mo bolaong jwa gagwe. A itshwantshisa le gone a eme go bapa le lebitla la ga mmagwe. “Baemedi ba dithuto tsa dipalo, ntseelang dikwalo tsotlhe ka tsweetswee,” ga bitsa Mme Nelao. Hilifa a bona ditshwantsho mo lokwalong la gagwe mme a leka go gagola tsebe eo, go ne go le thari. Moemedi wa moithuti o ne a setse a isitse lokwalo la gagwe go Mme Nelao.

When Hilifa tried to do his maths the numbers jumped around in his head. He couldn’t keep them still long enough to count them. He soon gave up. He thought of his mother instead. His fingers began to draw his thoughts. He drew his mother in her bed. He drew himself standing beside his mother’s grave. “Maths monitors, collect all the books please,” called Ms. Nelao. Hilifa suddenly saw the drawings in his book and tried to tear out the page, but it was too late. The monitor took his book to Ms. Nelao.

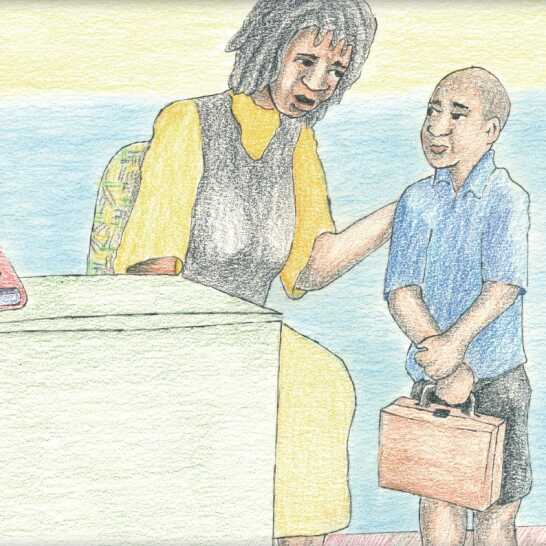

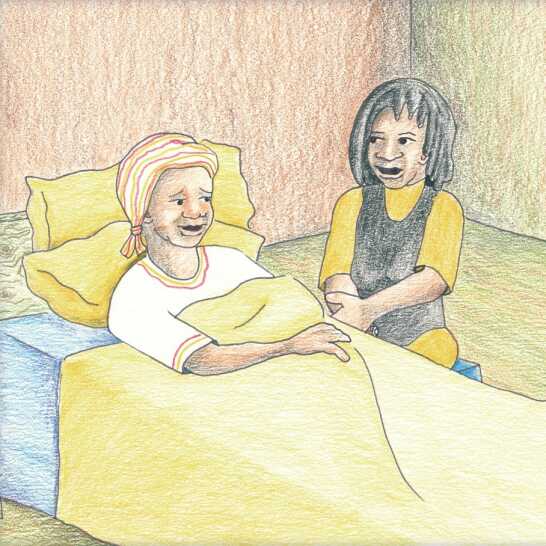

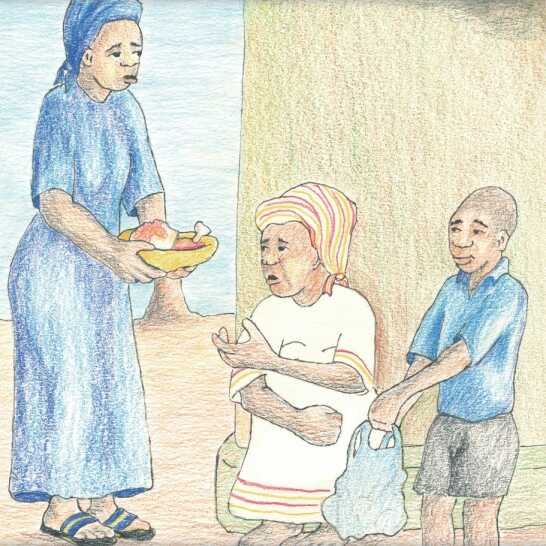

Mme Nelao a lebelela ditshwantsho tsa ga HIlifa. E rile baithuti ba tswa ba boela malwapeng a bitsa a re, “Tla kwano Hilifa. Ke batla go bua le wena.” “Molato ke eng?” a mmotsa ka iketlo. “Mme o a lwala. O mpoleletse a re o na le AIDS. A o tlaa tlhokafala?” “Ga ke itse, Hilifa, mme gone o na le mogare wa AIDS fa a lwala thata. Ga go na kalafi.” Ya nna mafoko ao gape, “Ga go na kalafi. Ga go na kalafi.” Hilifa a simolola go lela. “Tsamaya o ye lwapeng, Hilifa,” ga bua morutabana. “Ke tlaa tla go tlhola mmaago.”

Ms. Nelao looked at Hilifa’s drawings. When the children were leaving to go home she called, “Come here Hilifa. I want to talk to you.” “What’s wrong?” she asked him gently. “My mother is ill. She told me she has AIDS. Will she die?” “I don’t know, Hilifa, but she is very ill if she has AIDS. There is no cure.” Those words again, “No cure. No cure.” Hilifa began to cry. “Go home, Hilifa,” she said. “I will come and visit your mother.”

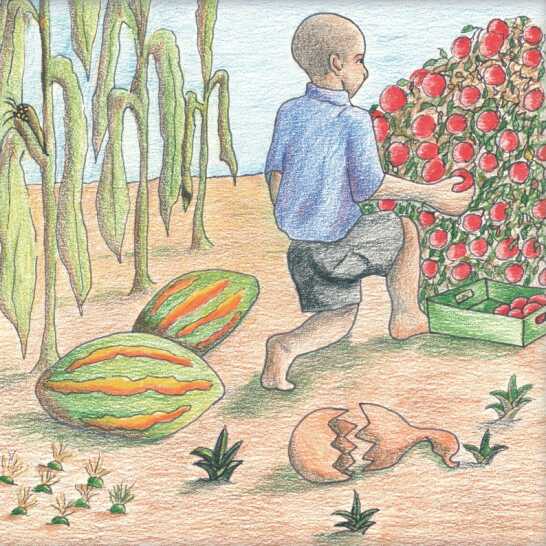

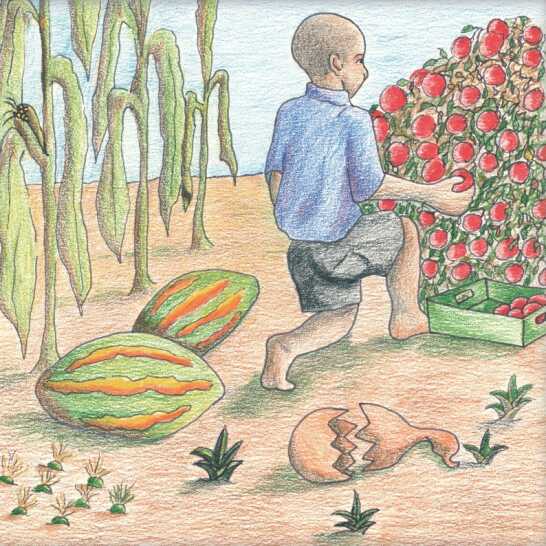

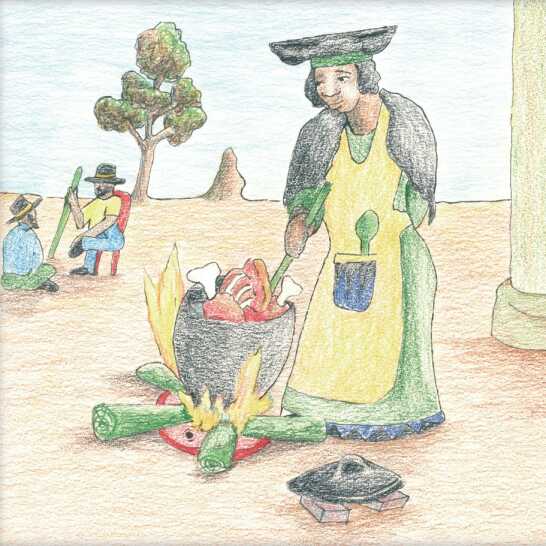

Hilifa a boela gae mme o fitlhetse mmaagwe a baakanya dijo tsa motshegare. “Ke go apeetse gompieno, Hilifa, mme gone jaana ke lapile. Tlhokomela tshimo ya merogo mme o ise ditamati dingwe ko lebenkeleng. Ba tla re di rekisetsa.” Morago ga dijo tsa motshegare ke fa Hilifa a ya kwa polotong ya merogo. A leba merogo e mebala e e tiileng, ditamati le ditshilisi tse di bohibidu jo bo tiileng, dinawa tse di telele tsa mmala o motala, sepinasi se se mmala o motala o o gateletseng, ditlhare tse di tala tsa patata le mmidi o moleele o o buduleng. A nosa tshimo mme a tsholetsa kgetse e e tletseng ditamati tse di hibidu tse di buduleng go di isa kwa lebenkeleng. “Go tla diragala eng ka tshimo ya bone fa mmaagwe a ka tlhokafala?” a ipotsa.

Hilifa went home and found his mother preparing lunch. “I’ve cooked for you today, Hilifa, but now I am very tired. Look after the vegetable garden and take some tomatoes to the shop. They will sell them for us.” After lunch Hilifa went to the vegetable plot. He looked at the bright colours of the vegetables, bright red tomatoes and chillies, long green beans and dark green spinach, the green leaves of the sweet potato and tall golden maize. He watered the garden and picked a bag full of ripe red tomatoes to take to the shop. “What would happen to their garden if his mother died?” he wondered.

Mme Nelao o gorogile nakwana morago ga Hilifa a sena go tsamaya. O ntse nako e teleele koo a bua e mmaagwe. A botsa mmagwe Hilifa potso, “Mme Ndapanda, a o tsaya dipilisi tsa gago tsa mogare wa AIDS?” “Morago ga monna wa me a sena go tlhokafala ke ne ka tlhabiwa ke ditlhong go ya go bona ngaka,” a bolelela Mme Nelao. “Ke ne ke nna ke solofela gore ga ke a tsenwa ke mogare. E rile ke simolola go lwala ka ya kwa ngakeng mme ya nkitsise fa ke le thari. O ne a mpolelela gore molemo ga o kitla o kgona go nthusa.” Mme Nelao a bolelela mme Ndapanda se a neng a tshwanetse go se dira go ka thusa Hilifa.

Ms. Nelao arrived soon after Hilifa left. She spent a long time talking to his mother. She asked Hilifa’s mother, “Meme Ndapanda, are you taking the medicine for AIDS?” “After my husband died I was too ashamed to go to the doctor,” she told Ms. Nelao. “I kept hoping I wasn’t infected. When I became ill and went to the doctor she told me it was too late. The medicine would not help me.” Ms. Nelao told Meme Ndapanda what to do to help Hilifa.

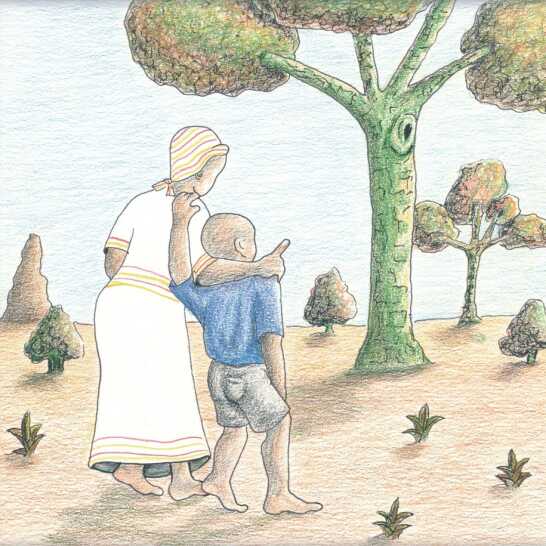

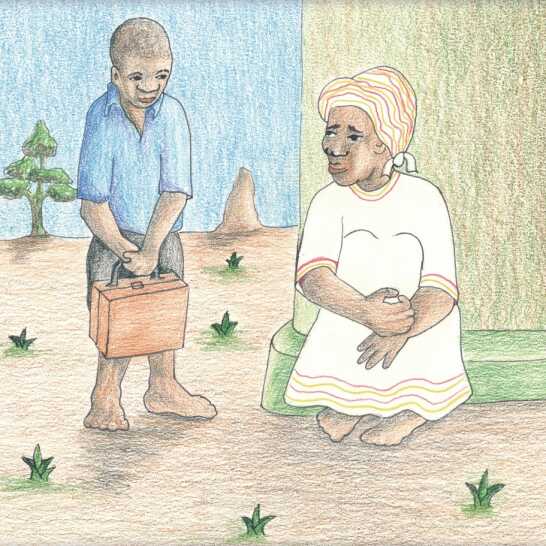

E rile Hilifa a goroga fa gae, mmaagwe a mmotsa a re, “Hilifa, morwaake, ke batla go tsaya motsamaonyana le wena, a o tla kgona go nthusa?” Hilifa o ne a tsaya letsogo la ga mmaagwe mme a itlhabetsa mo go ene mme ba ya kwa ditlhareng tse di telele tsa mmitlwa di golang teng. A mmotsa potso, “A o gakologelwa o tshameka kgwele ya dinao le ntsalao yo o bidiwang Kunuu? O ile wa ragela kgwele/bolo mo setlhareng mme e ile ya ngaparegela mo mmitlweng. Rrago o ne a ngapiwa ke mamitlwa a ntse a go e pagololela.”

When Hilifa came home his mother asked him, “Hilifa, my son, I want to take a walk with you. Will you help me?” Hilifa took his mother’s arm and she leaned on him. They walked to where the tall thorn trees grew. She asked him, “Do you remember playing football here with your cousin Kunuu? You kicked the ball into the tree and it got stuck on the thorns. Your father got scratched getting it down for you.”

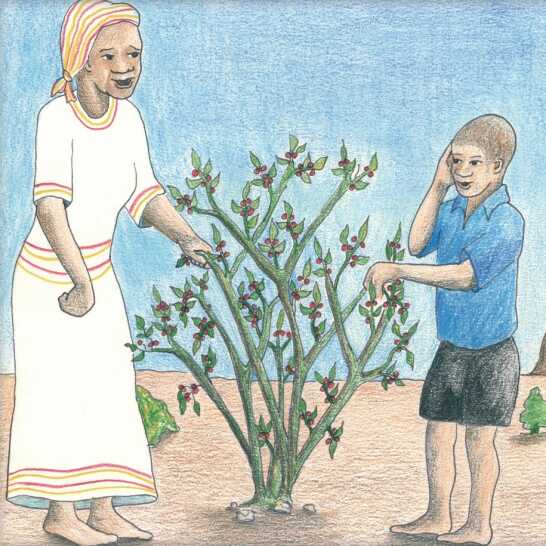

“Bona, setlhare sa ditlhekwa ke sele, tsamaya o ye go re fulela ditlhekwa tse re tla di isang kwa gae.” Fa Hilifa a santse a fula ditlhekwa tse di botshe tseo, mmaagwe a re go ene, “A o gakologelwa o le monnye o ja ditlhekwa le dithapo tsa tsone? Ga o ka wa ya kwa ntlwaneng mo selekanyong sa beke!” “Ee, mogodu wa me o ne o le botlhoko thata,” ga gakologelwa Hilifa a ntse a tshega.

“Look, there’s an omandjembere bush. Go and pick some to take home.” When Hilifa was picking the sweet berries, she said, “Do you remember when you were small you ate the berries and the seed inside. You didn’t go to the toilet for a week!” “Yes, my stomach was sooo sore,” remembered Hilifa, laughing.

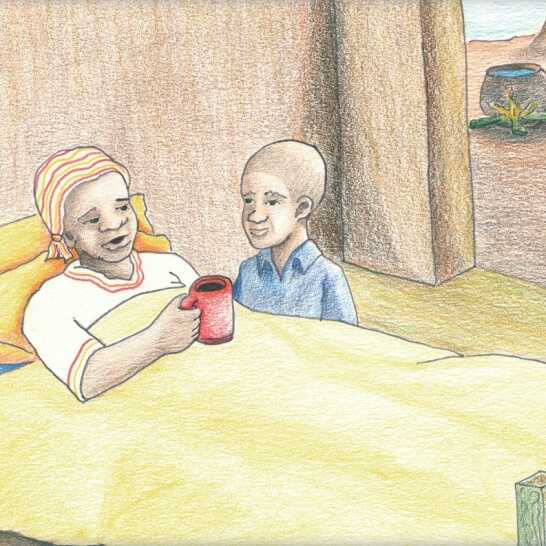

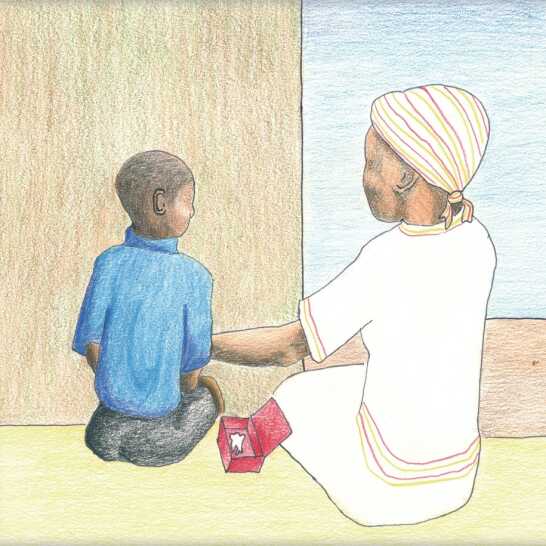

Fa ba goroga mo lelwapeng ke fa mmaagwe Hilifa a lapile thata. Hilifa a dira tee. Mme Ndapanda a tsaya lebokoso le lennye go tswa fa tlase ga bolao. “HiIlifa, mo ke ga gago. Mo lebokosong le go na le dilo tse di tla go thusang go gakologelwa kwa o tswang teng.

When they got home Hilifa’s mother was very tired. Hilifa made some tea. Meme Ndapanda took a small box from under her bed. “Hilifa, this is for you. In this box are things that will help you remember where you come from.”

A ntsha dikgopotso go tswa mo lebokosong bongwe ka bongwe. “Se ke setswantsho sa ga rraago a go tsholeditse. O ne o le ngwana wa gagwe wa leitibolo. Ke setshwantsho se ke se tshwereng fa ke go isitse kwa go mmemogolo le rremogolo wa gago. Ba ne ba itumetse thata. Se, ke sa fa o latlhegelwa ke leino la gago la ntlha. A o gakologelwa jaaka o lela mme ke go tshepisa gore a mangwe a tla santse a gola? Se ke sepelete se rraago a se nneetseng fa re digela ngwaga re nyalane.”

She took the mementos out of the box one by one. “This is a photo of your father holding you. You were his firstborn son. This photo is when I took you to see your grandparents, they were so happy. This is the first tooth you lost. Do you remember how you cried and I had to promise you that more would grow. This is the brooch your father gave me when we were married for one year.”

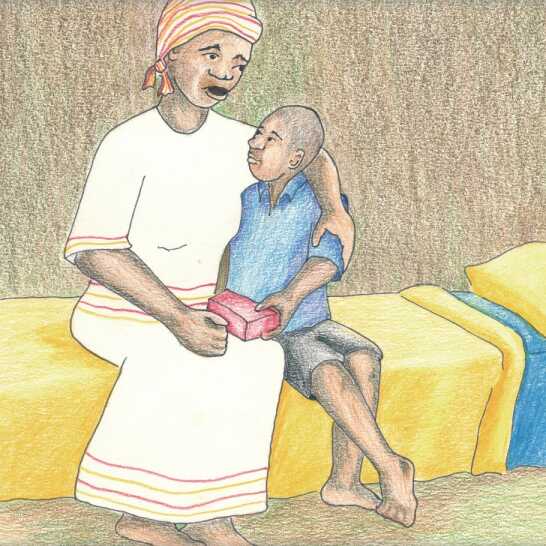

Hilifa a tshwara lebokoso mme a simolola go lela. Mmaagwe o mo tshwarelela gaufi le ene a bo a rapela, “A Morena Modimo o go tlamele o go babalele.” O ne a mo tshwere fa a ntse a bua, a re, “Hilifa, morwaaka, o a itse fa ke lwala thata mme e bile ke tla tsamaya go nna le rraago mo nakong e khutshwane. Ga ke batle gore o hutsafale. Gakologelwa gore ka e a go rata. O gakologelwe le gone ka fa rraago a neng a go ratile ka gone.”

Hilifa held the box and began to cry. His mother held him close by her side and said a prayer, “May the Lord protect you and keep you safe.” She held him as she spoke. “Hilifa, my son. You know that I am very ill, and soon I will be with your father. I don’t want you to be sad. Remember how much I love you. Remember how much your father loved you.”

Mmaagwe a tselela ka go bua, a re “Malomaago Kave yo o nnang kwa Oshakati o re romelela madi fa a kgona. O mpoleletse gore o tla go tlhokomela. Ke buile le ene ka ga gone. O tla ya kwa sekolong le morwae ebong Kunuu. Kunuu omo mophatong wa bone jaaka wena. Ba tla go tlhokomela sentle.” “Ke rata Malome Kave le rakgadi Muzaa,” ga bua Hilifa. “E bile ke rata go tshameka le Kunuu. A o tla fola fa ba ka go tlhokomela?” “Nnyaa, morwaaka, ga ke kitla ke tokafala. O ntlhokometse sentle e bile ke motlotlo go nna le morwa yo o siameng jaaka wena”

His mother continued, “Uncle Kave from Oshakati sends us money when he can. He told me that he will care for you. I have talked to him about it. You’ll go to school with Kunuu, his son. Kunuu is in Grade 4 like you. They will take good care of you.” “I like Uncle Kave and Aunt Muzaa,” said Hilifa. “And I like playing with Kunuu. Would you become well if they look after you?” “No, my son. I won’t become well. You look after me very well. I am proud to have such a good son.”

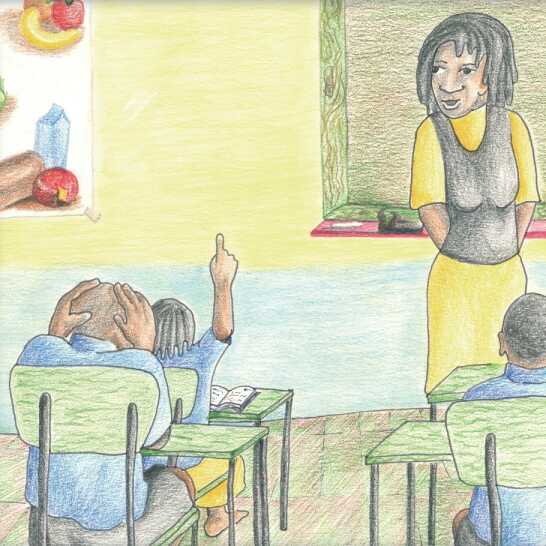

Mo mosong o o latelang kwa sekolong mme Nelao o ne a ba ruta ka ga HIV le AIDS. Baithuti ba ne ba lebega ba tshogile. Ba utlwile ka mogare o mo seromamoweng mme ga go ope yo o kileng a bua ka ga one kwa malwapeng. “Mogare o tswa kae?” ga botsa Magano. “O kgona go go tsena jang?” ga botsa Hidipo. Mme Nelao a tlhalosa gore HIV ke leina la mogare. “Fa motho a na le mogare wa HIV mo mading a gagwe o lebega a itekanetse. Re tla re o na le AIDS fa a koafetse/lwala thata.”

The next morning at school Ms. Nelao taught them about HIV and AIDS. The learners looked afraid. They heard about this illness on the radio, but no-one spoke about it at home. “Where does it come from?” asked Magano. “How do we catch it?” asked Hidipo. Ms. Nelao explained that HIV is the name of a virus. When a person has the HIV virus in their blood they still look healthy. “We say they have AIDS when they become ill.”

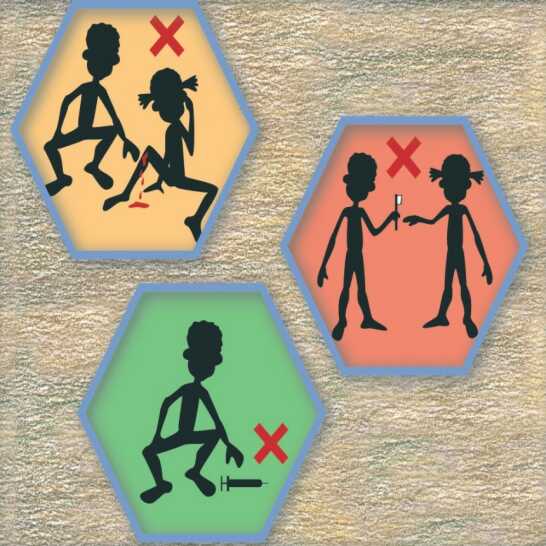

Mme Nelao o ne a tlhalosa ka mekgwa mengwe e motho a kgonang go tsenwa ke mogare wa HIV ka one. “Fa mongwe a na le HIV kgotsa AIDS re kgona go tsenwa ke mogare go tswa mo mading a gagwe. Ga re a tshwanela go abelana dithipana tse di bogale tse di beolang kgotsa dikgotlhameno. Fa re phungwa ditsebe re tshwanetse go dirisa dirisiwa tse di bogale le dimao tse di phepafaditsweng.” O tlhalositse ka fa dimao le didirisiwa tse di bogale di phepafadiwang ka teng. “Fa re ikgobatsa mme go nne le madi re tshwanetse go kopa mogolo go phepafatsa ntho eo. Re tshwanetse go fapha ntho eo go e babalela,” a ba itsise.

Ms. Nelao explained some of the ways we can be infected with HIV. “If someone has HIV or AIDS we can catch the virus from their blood. We should never share razors or toothbrushes. If we get our ears pierced we must use sterilised blades and needles.” She explained how needles and blades should be sterilised. “If we hurt ourselves and there is blood we must ask an adult to clean the wound. We must cover the wound to protect it,” she told them.

Morago ga moo a ba bontsha tshate. “Mo ke mekgwa yotlhe e o ka sekeng wa tsenwa ke mogare ka one,” A ba itsise. “Ga o ka ke wa tsenwa ke mogare ka go tlhakanela pitsana ya ntlwana kgotsa go tlhapa mmogo. Go tlamparelana, go atlana kgotsa go tshwarana diatla le motho yo o nnang le HIV kgotsa AIDS le gone go siame. Go siame go abelana dikopi le dijana le motho yo o nnang le HIV kgotsa AIDS. Ga o ka ke wa tsenwa ke mogare go tswa mo mothong yo o gotlholang kana yo o ithimolang. Ga o kgone go tsenwa ke mogare le gone fa o longwa ke montsane kgotsa ditshenekegi tse di lomang jaaka dinta kgotsa dinta tsa malao.

Then she showed them a chart. “These are all the ways you can’t catch HIV,” she told them. “You won’t get HIV from using the toilet, or sharing a bath. Hugging, kissing or shaking hands with someone with HIV or AIDS is also safe. It’s OK to share cups and plates with someone who has HIV or AIDS. And you can’t catch it from someone who is coughing or sneezing. Also, you can’t get it from mosquitoes or other biting insects like lice or bedbugs.”

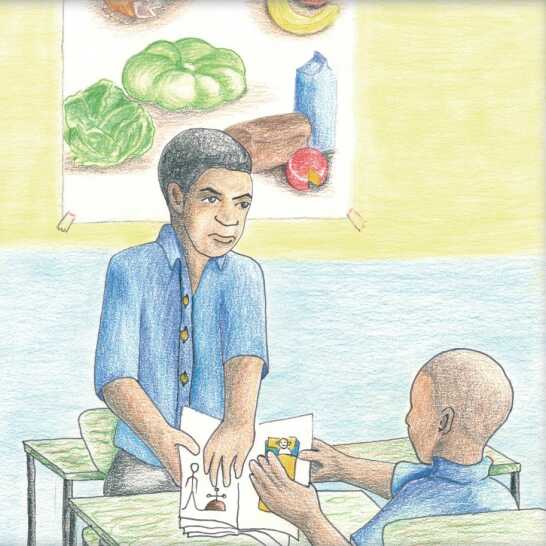

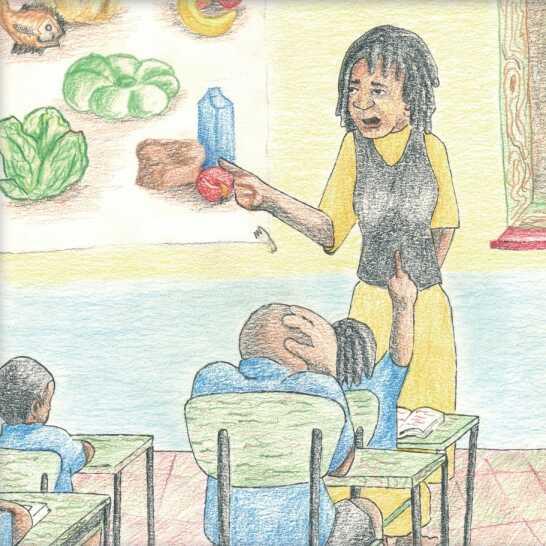

“O dire eng fa o na le jone?”, ga botsa Magano. “Ehe, se o tshwanetseng go se dira ke go itlhokomela le go ja dijo tse dintsi tse di itekanetseng. Lebelela tshate ya dijo,” ga bua morutabana. “Ke mang yo o gakologelwang dijo tse di siametseng go jewa?” a botsa.

“What do you do if you’ve got it?” asked Magano. “Well, you must take care of yourself and eat lots of healthy food. Look at our food chart,” she said. “Who can remember what food is good for you?” she asked.

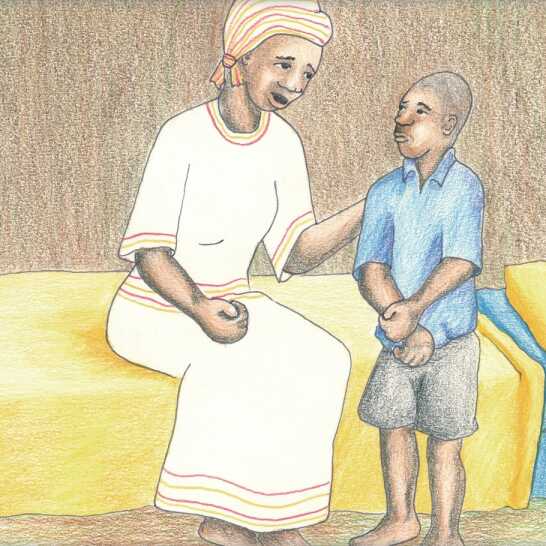

E rile Hilifa a goroga mo gae a bolelela mmaagwe ka se a se ithutileng kwa sekolong ka letsatsi leo. “Mme Nelao o re boleletse ka ga HIV le AIDS le ka fa re ka tlhokomelang motho yo o lwalang ka teng. Magano le Hidipo ba tlile go nthusa ka ditiro tsa mo gae re be re dira tirogae mmogo,” a mmolelela.

When Hilifa got home he told his mother what he had learned at school that day. “Ms. Nelao told us about HIV and AIDS and how to look after someone who’s ill. Magano and Hidipo are going to help me with my chores and we will do our homework together,” he told her.

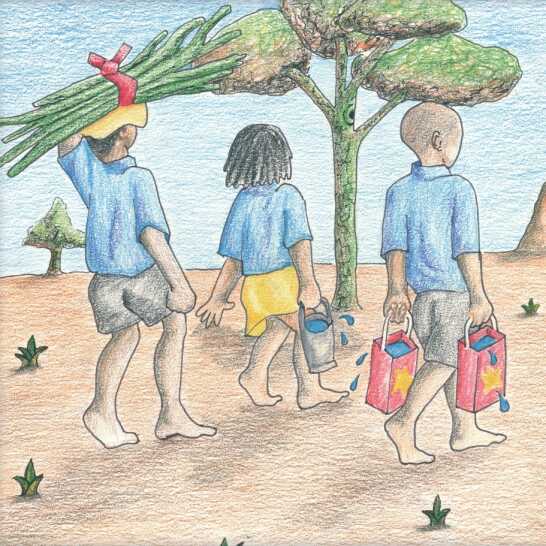

Mo motshegareng oo Magano a tla a bo a thusa Hilifa go ga metsi. Hidipo ene a mo thusa ka go rwalela dikgong. Morago ga moo ba nna fa tlase ga setlhare sa marula ba dira tirogae ya bone.

That afternoon Magano came and helped Hilifa to fetch water. Hidipo helped him to gather firewood. Then they sat and did their homework in the shade of the marula tree.

Mme Nelao o itsisitse baagisanyi ba ga Hilifa gore mosimane o tlhokometse mmaagwe. Ba ile ba tshepisa gore ba tla mo thusa. Bosigo le bosigo moagisanyi yo mongwe o ne a ba tlela dijo tse di bothito go ja. Hilifa o ne a ba naya merogo e se kae go tswa mo tshimong.

Ms. Nelao had also told Hilifa’s neighbours that he was looking after his mother. They had promised to help him. Every night a different neighbour came with hot food for them to eat. Hilifa always gave them some vegetables from the garden.

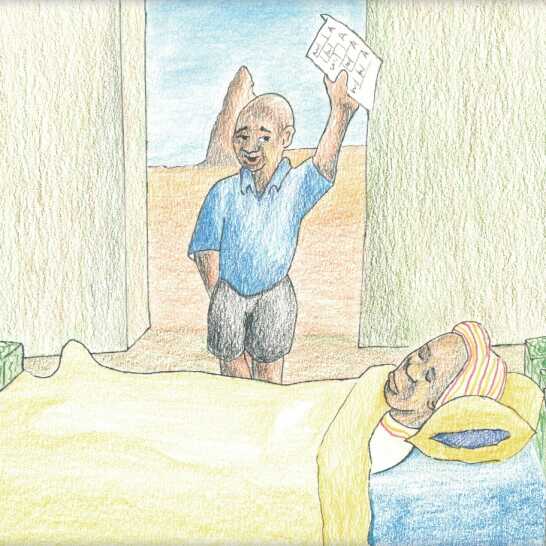

Ka letsatsi la bofelo la setlha Hilifa o ne a itumetse thata. O tabogetse kwa gae go ya go bontsha mmaagwe repoto ya gagwe. O ne a tabogela mo jarateng a bitsa a re, “Mma. Mma. Bona repoto ya me. Ke bone ‘A’, ‘A’ le boA ba bantsi. Hilifa o fitlhetse mmaagwe a rapame mo boloaong. “Mma!” a bitsa. “Mma! Tsoga!” Mmagwe ga a aka a tsoga.

On the last day of the school term Hilifa was very happy. He ran home to show his mother his report card. He ran into the yard calling, “Mum. Mum. Look at my report card. I have got ‘A’, ‘A’, and more ‘A’s’.” Hilifa found his mother lying in bed. “Mum!” he called. “Mum! Wake up!” She didn’t wake up.

Hilifa o ile a tabogela kwa baagisanying. “Mme. Mme. Ga a tle a tsoga,” a lela. Baagisanyi ba ile ba tsamaya le ene kwa ga bone mme ba fitlhela maagwe a ntse a le mo bolaong. “Mmaago o tlhokafetse, Hilifa,” ba bua ka khutsafalo.

Hilifa ran to the neighbours. “My Mum. My Mum. She won’t wake up,” he cried. The neighbours went home with Hilifa and found Meme Ndapanda in her bed. “She is dead, Hilifa,” they said sadly.

Molaetsa o ne a utlwala ka ponyo ya leitlho ka ga loso la ga Mme Ndapanda. Ntlo e ne e tletse balosika, baagisanyi le ditsala. Ba ne ba rapelela mmaagwe Hilifa e bile ba opela difela tsa tumelo. Ba bua ka dilo tsotlhe tse dintle tse ba neng ba di itse ka ga mme Ndapanda.

Very quickly the news spread that Meme Ndapanda was dead. The house was full of family, neighbours and friends. They prayed for Hilifa’s mother and sang hymns. They talked about all the good things they knew about her.

Mmangwane Muzaa o ne a apeetse baeng botlhe. Malomaagwe Kave o ne a mmolelela gore ba tla ya Oshakati le ene morago ga phitlho. Rremogoloagwe ene o mmoleletse dikgang ka ga mmaagwe fa a santse a le monnye.

Aunt Muzaa cooked for all the visitors. Uncle Kave told Hilifa that they would take him back to Oshakati after the funeral. His Grandfather told him stories about his mother when she was a little girl.

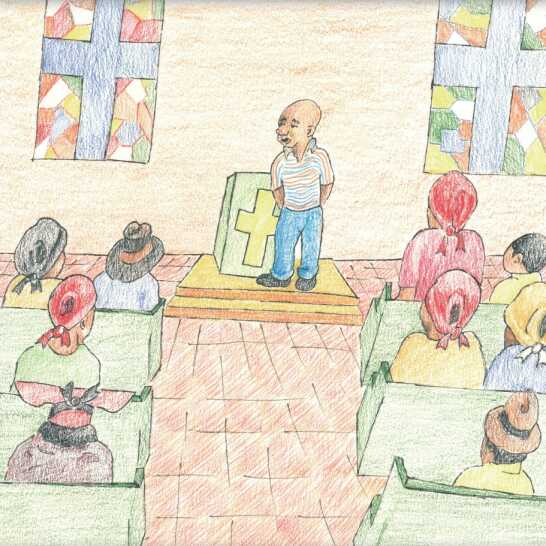

Kwa phitlhong, Hilifa o ne a ya kwa pele ga phuthego mo kerekeng mme a bolelela mongwe le mongwe ka ga mmaagwe. “Mme o ne a nthatile gape o ne a ntlhokomela sentle. O mpoleletse gore ke ithute thata gore ke kgone go bona tiro e siameng. O ne a batla gore ke nne ke itumetse. Ke tla ithuta gape ke bereka thata gore a nne motlotlo ka nna.

At the funeral Hilifa went to the front of the church and told everyone about his mother. “My mother loved me and looked after me very well. She told me to study hard so that I could get a good job. She wanted me to be happy. I will study hard and work hard so that she can be proud of me.”

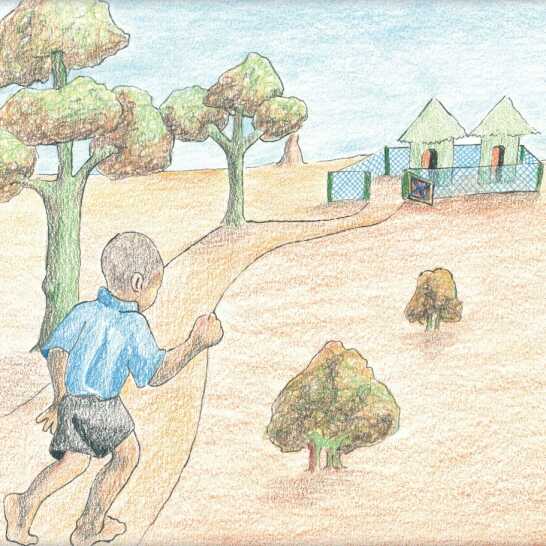

Morago ga phitlho, malomaagwe Kave le rakgadiagwe Muzaa ba thusa Hilifa go phutha dilwana tsa gagwe tse a tla yang ka tsone kwa Oshakati. “Kunuu o itumeletse go ya go nna le tsala e ntsha,” ba mo itsise. “Re tla go tlhokomela jaaka morwa wa rona.” Hilifa o ne a laela legae morago a palama thekisi le bone.

After the funeral Uncle Kave and Aunt Muzaa helped Hilifa to pack his things to take to Oshakati. “Kunuu is looking forward to having a new friend,” they told him. “We will care for you like our own son.” Hilifa said goodbye to the house and got into the taxi with them.

Written by: Kandume Ruusa, Sennobia-Charon Katjiuongua, Eliaser Nghitewa

Illustrated by: Jamanovandu Urike

Translated by:

Language: Setswana

Level: Level 5

Source: Orphans need love too from African Storybook

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.